Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Early England and the Saxon-English by William Barnes, 1869.

Saxon-English Laws

The ground of Saxon-English law was the Burh, or Borough, sometimes called the free-burgh or free-borough, or in later times frank-pledge.

The first meaning of burgh was a banking or mounding up, as a stronghold for safety, and then a safeguard, by word or pledge.

Hence to borrow was to take on pledge of giving back, and to bury is to bank up; and Wycliffe uses Biriel for a grave-mound or tomb. A borough, or burh (town) was so called as a banked or mounded hold, though politically a borough might be so called from the burh or fellow pledgeship of its burgesses.

The Saxon-English boroughship was that every ten free men or landholders were bound together to answer to the law for the lawful life of each of them; so that there were nine pledges to bring each man to right his wrongs. If one broke the law and fled, the others were to bring him, or his kindred, within a month, to answer for his crime, or to answer for him themselves.

Women, girls, and boys under twelve years old, were under the wardenship or burhship of their husbands or fathers, or free-men next-of-kin.

These boroughships of ten men were called Tithings or Tenthings, and the divisions above the Tithings were the Hundreds.

The Tithings seem to have been formed by the Saxon-English; and Blackstone and others have thought that the hundreds were formed by King Alfred. They were not, however, formed by any code of our Saxon-English kings, and Cantrevydd, or divisions of a hundred hamlets or landlordships were known to Welsh law of seemingly very early times of Saxonless Britain; and the heads or motemounds of many of our hundreds are in oustep-spots, where there was never a hamlet of English people, and the British Cantrevydd were made of ander-shares very unlike our Tithings.

There are traces of hundredship among the Romans. The Centuria sounds as if it were first a Cantrev of a hundred hamlets (trevydd) and the Centurion (Centurio) would seem to be, as the Saxon-English Hundredes earldor, the elder or head of his hundred; and if Tribis, a tribe, was at first, as the British Trev, a cluster of abodes, then we can understand why the centurion was chosen by the Tribunes (Tribuni) of the people, or the heads of the Trevydd.

The Saxon-English most likely found the hundreds, already formed by the Britons upon the Boroughship of tribes, or kindreds, and, as the English did not fill up the hundreds by tribes, for that they settled on the land only as freemen and not each as a man with his kindred at home, in Anglen or Saxony, so instead of the burh of kindred, which they could not have, they formed such an one as they could, that of freemen.

When the hundreds or cantrefydd were first formed? they most likely had each a hundred hamlets or landlordships, but when the tithings were formed it would seem that the hundreds had, as they now have, some more and some less than ten tithings.

The end of the boroughship of hundreds and tithings, was peace, and right, and the amending of wrongs; or, as Alfred says, that we should all be of one friendship or one foeship:—"Đat we waeron ealle on ánum freondscipe oᵭᵭe feondscipe."

The Welsh Laws say the laws were made for three ends; 1.—That men may leam what is wrong-doing, and keep from it. 2. That wrong which may have been done may be amended. 3. That wrong-doers may be punished by geald, fine, or otherwise.

The Laws of Eᵭered say:—"Every man shall have a true burh, that might hold him to right;"and the Laws of Edgar are " that if any one should do evil and flee, the burh should bear that which he should bear."

If a guilty man could not be found or brought to right, as if he had slain a man, and then drowned or hanged himself, his burhmen were free from their geald by the oath of a jury of their peers.

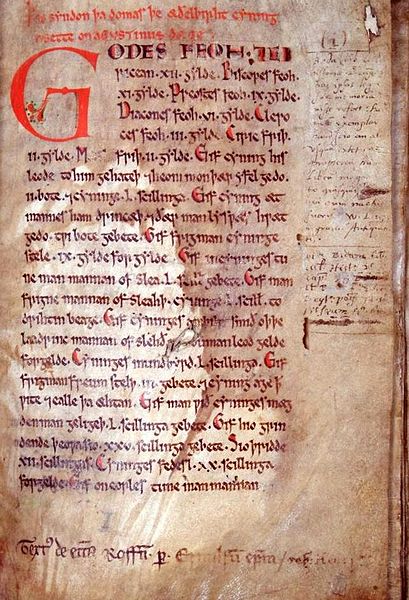

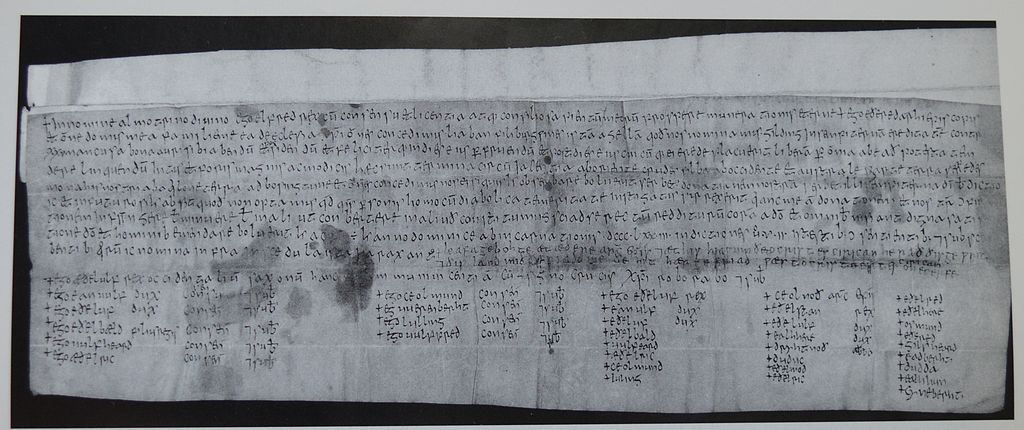

The codes of Saxon-English laws now left to hand are the laws of Eᵭelbert, Hloᵭar, Edric, and Wiᵭrald, of Kent; Ina, of Wessex; and Offa, of Mearc or Mercia.

After the union of the states, those of Alfred, which were mainly taken from former ones of Edward the Elder, and Eᵭelstan.

By the Saxon-English law, a price was set on a man's head, and on every kind of his goods; and the man that wrongfully took his life or goods was guilty of the fine.

The money fine for a crime was called the geald, whence our word guilt, which means what is owed to justice; but the geald, or blood-money, for a man's life was called the wergeald; the ware, or ward geald, or protection money. Or, if wer means a man, as it has been understood by some readers, a wergeald is the mangeald. Though it seems likely that, as a German scholar has hinted, wer means a man, in so far as he was wared, or warded by the wergeald.

We have many fellow stems of waer.

Beware is not "Be thou, or you ware," but it is the verb Bewaerian, to Byware, or Byward. Beware, ward or fence yourself. Weer, in North English, is to ward or keep off, and to ware one's money, is to take care of it.

A Wear, or Were, is a motuid, or dam to ward back fish or water.

A Warth, in North English, is a dam or ford.

To Warne, waren, a man is to beware or ward him, by words, against the evil of some deed.

A Warrant is what bewares or wards a man, on the doing of some office.

Thence a warden, or warder, is one who wards or wares, and a ward is one wared or warded by a warden.

A Warren is a warded or fenced covert.

There were sundry wergealds for a king, noble, eᵭeling, earldorman, thane, or ceorl; and the word mostly used for the paying of the geald was Betan or Gebetan, to amend or make up. Give to boot or amendment.

Blood Wrongs

In lands of patriarchial headship, the house-father is the head of his household; wife, children, and others, and warden of their lives.

Of such households may be formed tribes, and, at last, great tribes of house-tribes or kins (cin, in old English), and the head of a kin, kindred, or great tribe, is called by sundry names among sundry people; as in Saxon-English a cin-ing, king, or kin-head.

The tribe law is mostly that if a man of the tribe, A, should slay one of a tribe, B, there must be a clearing of blood by the death of the slayer; or, it may be, if he is shielded by his tribe, that some man of the tribe should die by the tribe of the slain.

Or by a straiter law, as that of the Mosaic law, that the manslayer shall be slain by a kinsman of the dead man, as by the avenger or redeemer of blood: the Goel-ha-dum, who was the eldest first-born of the kin; or that a kinsman of the slayer may be slain by a kinsman of the slain.

Or again, to save bloodshed, that a compensation of blood-money shall be given to the kindred of the slain by the kindred of the slayer, which blood-money was called by the Saxon-English the geald, by the Welsh galanas, and by the Arabs Thar.

If the blood-money be withholden, the wronged tribe may clear the blood by raid of war, in booty, or in blood for blood.

Among the Arabs the call for blood-money or blood, reaches by law, as it reached by the old British law, to the fourth kindred of the slayer, reckoned downward and sideways; and thus men have unwittingly justified the Word of God in the Commandment, that He visits, in worldly life, and not on the soul, the sins of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation; and indeed the Commandment is shown in strength in the penal colony at Sydney, where, as it is said, it takes three generations to wear out the taint of convict blood, and make the crime-tainted man's offspring pure, and welcome to the untainted; and, as it is said, it takes three generations to make a gentleman.

And it is said that the Guernsey law calls on the kindred, out to the third remove, of a man of vicious life to pay for his sustenance in the poor-house.

Some crimes of less guilt than capital ones were rated by whipping, but theft, robbery, perjury, burning, house-breaking, and breaking of the peace by fighting, were bound by high fines.

On some crimes the law sets the fine straitly, while on others it sets a body-pain, which might be bought off by a geald.

A Welshman's skin, by the laws of Ina, was rated by a hide-geald, by the payment of which he might buy it from the whip.

Crime is a wrong to a man wronged, and a wrong to the king, as keeper of the peace, and of justice; and so, in many law-breaches, a geald was paid to the wronged man, and a fine, called a wite, to the king.

The Saxon-English laws aimed at hindering of crime, or a righting of a wrong already done. We, in our laws, hardly aim at all at the righting of criminal wrongs. We think only of the wite for the law-breach, and forget the geald for righting the wrong to the loser by the deed. No wergeald was paid for a thief or robber killed in his crime.

If a free-man had been a man of such an unlawful or bad life that he had spent all his wealth in gealds, or vice, or idleness, a landowner or monastery might give a pledge as borough for him, and was then said to thingian (to thing) for him; ᵭingian meaning to answer, in the way of pledge or bail.

The man for whom another had thinged then became his theow, or an over-thinged man, and was under his hand, and unfree; and was sometimes called a wite-theow, or fine-theow: and if a man newly become a wite-theow had been guilty of an unamended thievery while he was free, the wronged man was to take a whipping of him, "ane swingelan aet him."

If a bad man could not find a tithing or lord to thing for him, his friends were warned to bring him to the Folemo’t (Folk-meeting), and find him borough.

If none would receive him he was outlaw, (utlaga) and bore a wolfs head.

It might be thought that the wite-theow might flee from his lord, or thinger; but there was a heavy fine for the harbouring of a runagate; and if a man slew a wite-theow, he should pay the lord his wergeald; and no theow might be sent beyond the sea. And if a householder should receive any unknown man for more than three nights, without a recommendation from his borough, he would thereby become borough for him.

Under the Saxon-English laws there was not much "doing of time" within the walls of a jail, built as such, as wrongs were mostly righted by the geald; and few men, were shut up in idleness to be kept by the crimeless. At times, however, criminals might have been shut up for longer or shorter times—hours or days—and the place of confinement was called a Cwaertern, which might have become our word Quarters.

It may well be thought that the law of imprisonment, and the handling of the prisoners, are improved since the time of Charles the Second. The Habeas Corpus Act and the Insolvency Laws, are a great shield of freedom against wrongful and malicious imprisonment; and care has been bestowed on the bettering of imprisonment into its best form for its best end.

Let it be allowed that our laws of imprisonment are raised to a better form on a measure of time of 200 years; yet we can hardly hold that they have been so bettered on a longer measure of time, 1,200 years; inasmuch as among the Saxon-English sentences of imprisonment were almost unknown.

"Good and wise Saxon-English," one may be ready to cry, "to live in community without a jail.”

No, not so good; since they had theowship, or an open air slavery.

In every state, men who cannot hold their freedom wisely and righteously, but work by it against the very end of the statelife, as a murderer or thief, it is found needful to take it from them.

Some of our criminals lose their freedom as slaves to the state, in jails, or in working gangs at convict-prisons, or in the colonies; and some of the Saxon- English criminals lost their freedom as theows to freemen.

If a man were slain his wergeald was paid to his kindred—two-thirds to his father’s side and one-third to his mother’s; but why was it not paid to his young children, or wife? It was paid to the men who would thing, or be borough, for his wife and children,

If a stranger or foreigner were slain the king had two-thirds of the wergeald and his kindred the rest. If he were without kindred the king had half and the lord of the manor half.

If a manslayer could not pay wergeald his kindred (mægas) paid half, and his borough half.

If a manslayer had no kindred by his father's side, his mother's kindred paid one-third, his borough one-third, and he fled for one-third.

If he had no kindred his borough paid half, and he fled for half.

There may be an objection that the equality of the geald itself made it unfair, since a wergeald was less heavy to a rich than to a poor man.

This is a sound objection; and one that lies against our lawbreach fines, for if a rich and a poor man, are both fined alike, for the like lawbreach, whereas the fine may be only an hour's income to the rich man, it may be a week's income of the less rich. But there are Saxon-English and Welsh laws, which show that they were less unfair than our own.

The laws of King Canute say "And a swa man biᵭ mihtigra, oᚦᚦe maran hades, swa sceal he deoper, for Gode and for woruld unriht gebetan."

"And so, as a man may be mightier, or a man of more wealth, so shall he the deeper before God and the world, amend his wrong.”

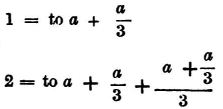

And on the mingling of more kinds of wickedness in a crime, or on the greater wealth of the criminal, the law put on a doable or threefold, or manifold geald: and in the Welsh law there was a rule of what was called Dyrchafael or Increase. If the normal fine were a, then, in cases of great wickedness or wealth,

The Welsh laws say no fine is owing for the intention, without the deed, which seems a fair law; but it is unlike our game laws, which make a man guilty of an intention to take game.

The Saxon-English laws made fine distinctions in cases of crime: for the burning of a tree, the geald was twice as much, as cutting it with an axe. "Forᚦam seo eax byᚦ meldana ᵭaes ᵭeof;" for the axe is a teller of the thief; and elsewhere it is said in the Laws of Ina.

Porᚦam ᵭe fy'r biᚦ ᵭeof.

For the fire is a stealthy thief.

The Law-courts or meetings, like our Sessions and Assizes, or Parliament, were called Gemot or Mot, from the verb metan to meet, and so a moot-point in law means a point for the decision of the Moot or Gemot, or Court.

There was a Hundredes gemot, or Hundred's court, holden every month, and a Burhgemot, the Borough or Freeborough Court, for business of the Buhrship, or confederation of free men, as pledges for each other; and it was holden three times a year.

The Scirgemot or Shiremote, like our county assizes, holden twice a year.

The Folcgemot or Folk-mote, gathered by ringing of a mot-bell on sudden occasions.

The Wittenagemot or Meeting of the Wise, as our Parliament

An oath was very hallowed and strong with the Saxon-English, and a man under some kinds of accusations could clear himself by his own oath, and that of twelve or more or less of his friends, or likes, that they believed him guiltless; as, if he had killed a man as a thief, or robber, or sold an unsound animal. A king's thane was to be tried by a king's thane, the lower man by lower men, and every man by his peers or likes.

Barnes, William. Early England and the Saxon-English. John Russel Smith, 1869.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.