Oral Literature of Pre-Christian Ireland

The ancient Irish produced an extensive oral literature marking the deeds and histories of their kings. They did not use writing until Ogham script, a simple form of Latin, was first introduced by the Romans.[1][2] Filid poets and lesser bards served as historians and genealogists. They studied for 10 years or more in druidic schools, memorizing extensive annals with the help of poetry and song. Poets occupied a uniquely protected position in Irish society. While they mostly composed praise-poems, an offended bard could unleash biting satire instead.[3]

Every three years, the master scholars of each túath came together to update the records and laws of the island. The Annals of Ireland claim to document Irish history from the Biblical flood to the late 17th century. Oral traditions continued well into the Middle Ages. Many surviving accounts of prehistoric Ireland come from 11th or 12th century manuscripts. Although relatively new, these texts tell stories hundreds or even thousands of years old.[4]

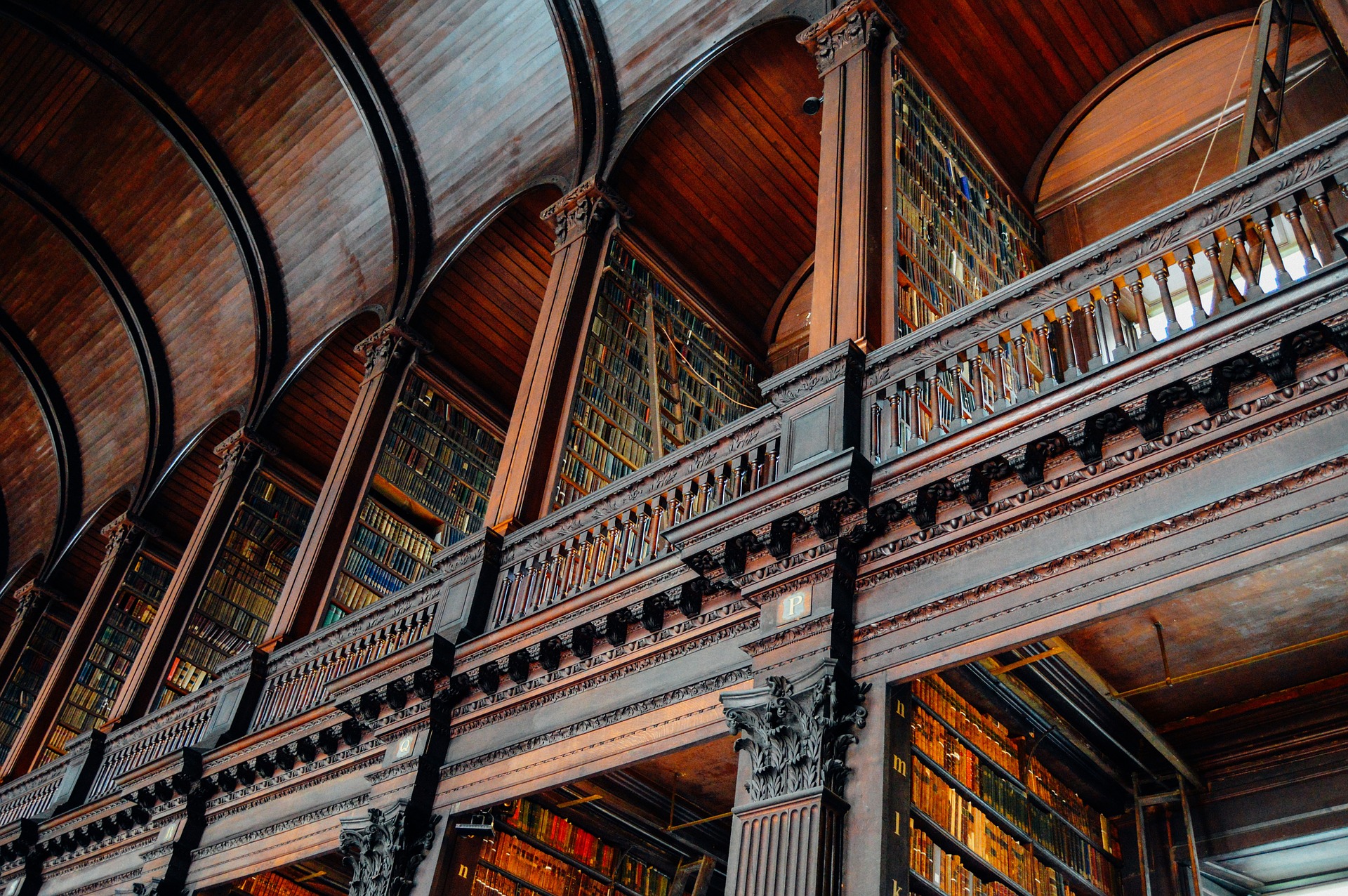

The Illuminated Manuscripts of Monastic Ireland

Irish monasteries not only embraced the art of writing but mastered it. Most literature of the time is dedicated to religion, philosophy, and history. Monks transcribed Christian texts in vellum manuscripts. In the process, they became highly skilled in the arts of calligraphy and illustration. Today, manuscripts like the 8th-century Book of Kells number among the most valuable works of art ever produced in Ireland.[5]

European Influences on Irish Literature

In time, the monastic monopoly on Irish literature declined. This came through church reforms and foreign conquests that would fundamentally change Irish life. Popular stories and medieval romances written in Irish entered circulation around the 12th century. French influences after the Anglo-Norman invasion increased their popularity. Ancient Irish tales saw renewed interest, adapted for medieval audiences.[6]

Following the Tudor conquest of the 17th century, English literary traditions became the standard. Use of the Irish language was discouraged, if not outright illegal in some places. Anglo-Irish writers like Jonathan Swift, caught between both cultures, were forced to choose a side in the ensuing upheaval. Satire, a specialty of Swift's, continued its role as a form of political criticism. The British Empire, Irish nationalists, and other public figures all faced open mockery from their opponents.[7]

The Gaelic Revival and Modern Irish Literature

Nationalist sentiments fuelled a literary renaissance in the 19th and 20th centuries. Irish poets and writers called back to romantic fairy tales and legends of the past to rekindle cultural pride. Irish literature flourished as part of the larger Gaelic Revival. Writers like W.B. Yeats, James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, J.M. Synge, and Samuel Beckett spearheaded the movement. The works they produced are now some of the most famous books and poems ever written.[8][9]

Bibliography

Dáithí Ó HÓgáin, The Sacred Isle: Belief and Religion in Pre-Christian Ireland (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Boydell Press, 1999).

Philip Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001), 2-12.

Joseph C. Walker, Historical Memoirs of the Irish Bards (Dublin: Printed for the author by Luke White, 1786), 6-19.

David N. Dumville, "A Millennium of Gaelic Chronicling" in The Medieval Chronicle, ed. Erik Kooper (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2004), 103-113.

Titus Burckhardt and Michael Oren Fitzgerald, The Foundations of Christian Art: Illustrated (Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2006), 5-11.

Padraig O'Neill, "Romance" in Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia, ed. Seán Duffy (New York: Routledge, 2005), 688-690.

Robert Mahony, Jonathan Swift: The Irish Identity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

Philip O'Leary, The Prose Literature of the Gaelic Revival, 1881-1921: Ideology and Innovation (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994), 40-49.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.