Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

Images from book by Fleet Marine Force Pacific, 1968.

From A Marines Guide to the Republic of Vietnam by Fleet Marine Force Pacific, 1968.

The Vietnamese appear at first to be quite different from us. Understanding the behavior of people who have been brought up in an unfamiliar culture isn't easy, and we must remember not to judge them by our own way of life. Learning Vietnamese social and religious customs is the first step in understanding and will help you avoid the mistakes others have inadvertently made.

First and most important don't look down on the Vietnamese even though they are obviously poorer than the average American. People know when they are regarded with contempt. You know when someone dislikes you-so do the Vietnamese.

Show special deference to old people. The Vietnamese have great respect for the elderly. Age is comparable to rank as far as they are concerned. They are highly sensitive to matters of rank and status. When you go into a hamlet, look for the oldest man first. He deserves the most respect, even though he may not be the hamlet chief. He will be able to locate the local authorities for you.

Be Respectful to Older People.

In fixed situations where you know you will be returning to a village several times, and there is no need to conclude your business quickly, don't rush your dealings with the people. No matter what your objective is, if you have the time, during your first visit to a hamlet or to an official don't mention what you want.

The visit should be only a social occasion and no business should be discussed. In your second visit you might partially discuss your business or refer to it indirectly. In the long run, you will save time by making many visits and being patient. The blunt approach natural to Americans must be curbed for best results. Ask a direct question and you are likely to get either an evasive answer or the response it is assumed you want to hear, whether it is correct or not. This is often the case when you request agreement and the other man is too polite to disagree directly. It is considered rude to make a request of an individual. Hint that you would like something done and let the Vietnamese volunteer to do it.

Don't pat a Vietnamese acquaintance on the back or on the head. In fact, "hands-off" is the rule, since such personal contact may be considered an affront to dignity. If you are a stranger in a hamlet, show friendliness to children through smiles and gestures but don't touch them. Vietnamese parents, like American parents, appreciate attention paid to their children by family and friends but dislike over-attention and the direct presentation of gifts by a stranger. Gifts to children, even a candy bar, should be channeled through parents and village elders.

Be especially careful in your conduct toward women. In Vietnam people show friendship publicly only with words and smiles. Shaking hands with women or patting them on the shoulder, actions which we take for granted, can cause resentment among the Vietnamese.

Learn to control your anger. Public displays of emotion are considered childish and immature by Vietnamese. So control your anger, affection, and other emotional impulses, and try to speak quietly at all times.

An invitation to eat in a Vietnamese home is not to be taken lightly; your host has spent time and money getting ready for your visit. Let the older people begin the meal before you do. Eat every bit of food put on your plate as a compliment to the hostess’ cooking, but do not clean the platter from which everyone is taking food, since this would make your hostess feel she had not prepared enough food to satisfy you.

The American use of first names among people they have only recently met can cause resentment among Vietnamese, who are more reserved in their personal relations. Stick to Mr. and Mrs., and let the Vietnamese get on the first-name basis when they are ready. This same reserve applies to introductions. It is much better to arrange an introduction through a mutual acquaintance than to introduce yourself to a Vietnamese.

In conversation with a new Vietnamese acquaintance, stick to small talk. Do not discuss politics, and do not use the words "native", "Asiatic" or "Indochina".

Even when talking to a Vietnamese whom you know fairly well, it is wise to avoid giving outright advice. Do not push your ideas; act on your ideas when possible, and let the Vietnamese observe the benefits to be derived by following your example.

A Quiet Hamlet.

If you have the opportunity to visit a Vietnamese family at home, remember to keep your feet on the floor. Propping your feet up on a chair or table is considered rude, and pointing your foot at someone (for example, sitting with an ankle on the opposite knee) is considered extremely insulting.

Even though you may admire an object in the house, it is bad manners to ask what it cost or where it was bought.

After you visit a Vietnamese at home, you can return his hospitality by inviting him to a restaurant—but make it an expensive restaurant, even though the food may be better at a cheaper place. The knowledge that he is being entertained expensively will please a Vietnamese more than a good meal would. Incidentally, the Vietnamese do not believe in "Dutch Treat.” The older man is expected to pick up the tab after joining someone by chance in a restaurant.

If you send a present to a family which has entertained you, send something for the children rather than for the wife. Since odd numbers are considered unlucky, send two inexpensive presents to a child, rather than a single expensive one. This is especially true of wedding presents; one present is thought to be a sign that the marriage will not last. Observing customs like these, even when they seem strange to you, will go a long way in creating good will.

All of the foregoing points should be remembered, but of greatest importance is the use of ordinary common courtesy which you would extend to your parents or friends.

Also of importance is the willingness to learn at least the basics of the Vietnamese language. It is a hard one, but learning enough to conduct simple conversations pays off in smoother work relationships

Marines learn basic Vietnamese.

Among the Vietnamese people, chronological time has little value. What may appear to Americans as laziness is actually the Vietnamese way of life. While we place a high premium on activity and progress, time tables, appointments, and schedules hold little interest for the average Vietnamese. What matters most to him is to strive for perfection, regardless of the amount of time required to do the job.

Unlike Americans, who have become known as people who change the physical world to suit their needs and desires, Easterners believe that the world around them is their fate and that it is necessary to strive for harmony with their surroundings. Many try to reduce their needs to a minimum necessary to sustain life and are amazed by the "needs" of Americans. Also, considering the fact that the average income of one Vietnamese peasant is slightly over $120 a year, it is hardly surprising that American needs are luxuries in their eyes.

Despite the signs of war, life goes on for the Vietnamese farmer.

A particular point for all to remember is that most Vietnamese are deeply motivated by their religion. A great significance is attached to religious places and things. Temples, shrines, and religious artifacts should be accorded respect. The Vietnamese National Flag should also be treated with such respect. A careless act on the part of a Marine can create considerable ill will that is most difficult to overcome.

In regard to the oriental respect for the dead, a reverence is shown for the burial sites. The Marine must pay particular attention to insure he does not violate this ground that the Vietnamese hold sacred. These grave sites are located all over the countryside and are characterized by burial mounds.

Note the graves in the upper part of the picture.

Looking at the Vietnamese as a man, we see him in a hamlet in the countryside supporting his family with what he can grow in his rice fields. His house is built for practical uses rather than beauty. He uses locally available materials such as bamboo, straw, mud and other products of the area. He extends the eaves well over the walls so that the heavy rains of the monsoons will not wash the walls away. He has very little formal education, but he is by no means stupid.

His hamlet is run by the hamlet chief and in turn, depending upon the number of hamlets in the village, the hamlet chiefs are controlled by the village chief. When any problems arise, the man seeks advice from his hamlet chief. This life, although humble, is extremely orderly. The Vietnamese people, much the same as the Marine Corps, have a chain of command. Before you have anything to do with the people, you must first contact the village and hamlet chiefs. They speak for their people and know all that occurs in their areas and would be embarrassed and indignant if bypassed.

By our presence, daily contact, and association with the local population, we can foster friendship and restore the confidence and loyalty of the Vietnamese people toward their government, both local and national. This can be accomplished by two primary means; first is our rapport with the Vietnamese people. This includes developing an appreciation for their customs, traditions and history; treating the people as hosts, which they are, and respecting their religious beliefs, shrines, graves and other places of endearment. Secondly, we can assist the local government in gaining the support of the population. By working with and through local officials and providing material and technical assistance through them, we can build their prestige in the eyes of the people.

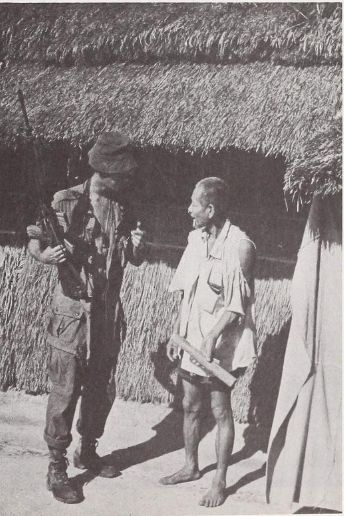

Medical Corpsman talks to Village Chief through Vietnamese interpreter.

If these points are held in mind by the Marine, they will undoubtedly serve him well during his stay in Vietnam. They will help to make his job easier and most likely will lead to a more enjoyable tour. The main task in Vietnam is by no stretch of the imagination a pleasant one; but with a little conscientious effort on the part of each individual Marine, the non-combatant civilians of South Vietnam will not be alienated towards the U. S. Forces. In fact, cultivating a spirit of cooperation with the populace will, in many cases, result in tactical benefits to the Marine operating in the area.

Outside the large cities, the routine of work goes on day after day without any pause on the seventh. Only when there is a national holiday or religious festival does the daily routine of "work, eat, sleep" come to a temporary halt. The chief Vietnamese festivals by the lunar calendar are:

The New Year, more commonly referred to as "Tet", Nguyen Dan, 1st through 7th day of 1st month

The Trung Sisters, Hai Ba Trung, 6th day of the 2nd month

The Summer Solstice, Doan Ngo, 5th day of the 5th month

Wandering Souls, Trung Nguyen, 15th day of the 7th month; also celebrated on the 15th day of the 1st and 10th months

Mid-Autumn, Trung Thu, 15th day of the 8th month

Tran Hung Dao, 20th day of the 8th month

Le Loi, 22nd day of the 8th month

Tet

Vietnamese Tet, the Lunar New Year, corresponds to Chinese New Year and occurs with the New Moon—late in January or early in February. It is essentially a three-day observance, the first being dedicated to ancestor worship; the second is for visiting parents, relatives, and friends; and the third is one of celebration "for the dead and the living."

The actual period of celebration is established by government announcement.

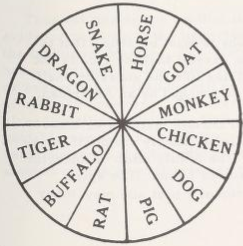

As noted above, the Vietnamese celebrate their New Year, Tet, according to the lunar calendar rather than according to our western calendar. The main differences in the lunar calendar and the western calendar are that the lunar months alternately have 29 and 30 days, and that the lunar years are recorded in twelve year cycles rather than in numerical succession such as 1967, 1968, 1969 as in the western calendar. The twelve year cycle is illustrated below:

Lunar Calendar

The year of the:

1967 Goat

1968 Monkey

1969 Chicken

1970 Dog

1971 Pig

1972 Rat

1973 Buffalo

1974 Tiger

1975 Rabbit

1976 Dragon

1977 Snake

1978 Horse

Fleet Marine Force Pacific. A Marine's Guide to the Republic of Vietnam. USMC, 1968.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.