Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Village Life Under the Soviets by Karl Borders, 1927.

The Village and the Villager

To understand the village in Russia it is necessary, first of all, to abandon most of the ideas we have associated with that term in America. The Russian farmer does not go to town on Saturday afternoon. He lives in town, with rare exceptions, and goes out to his land when it needs attention. Nor does the term imply a small population.

I have known villages with populations as high as ten thousand—as great as that of some of our cities that boast Great White Ways—which are nevertheless, true agricultural communities, the vast bulk of whose population is engaged in the actual cultivation of the soil. Even the centers of population listed in Russian statistics as towns or cities, as a matter of fact often have large agricultural populations, for the classifications are made on the basis of administrative function rather than on that of the occupations of the inhabitants.

Three sizes of villages are indicated by the terms posyolok, derevnya, and selo. The first may be a group of ten houses; the last, as I have said, may be a center of considerable population strung for miles along a wide dusty road or clustered about the banks of a stream, though the actual distinguishing feature of a selo is the fact that it boasts a church, while the derevnya does not.

From the outset of this study, too, the reader must be warned against general conclusions about “Russia.” It must be remembered that the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics, with its six autonomous republics and numerous small racial independencies within these larger divisions, occupies one-sixth of the landed area of the earth. This vast territory, stretching from the frozen tundra of the Arctic to the semi-tropical section of Trans-Caucasus, and filling the great gap between western Europe and Mongolia, contains within its borders not less than forty varied racial stocks, with even more differing dialects and languages. It counts as its subjects the nomad of the Kirghiz steppe, the Laplander, and the polished city dweller of Moscow or Leningrad.

Therefore, we must consider any general statements either as averages or efforts to appraise the medium, on either side of which probably lies an infinite shading in details. I have some personal knowledge of the villages of Leningrad Government in the north, Samara Government on the middle Volga, and the more recently settled and agriculturally advanced area of the North Caucasus. A crescent line drawn through these points will cut the principal agricultural areas and give a fair medium view of the village life of the Russian Socialist Federation of Soviet Republics, the center and the largest part of the Union.

In outward appearances, the village has probably changed little in centuries. Certainly Wallace's study of life and customs in the villages, written in 1875, after six years spent in intimate touch with all sides of Russian life, might, as far as much of its descriptive material is concerned, have been written yesterday.

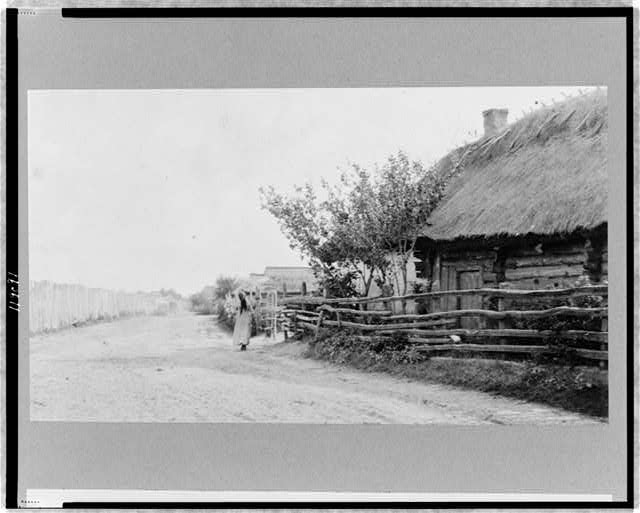

Two main types of village are determined by the building material used and by the setting. The village of the forested areas of the north is, of course, built of logs and set by pleasant lakes or the numerous streams that thread the fields and woods. The village of the vast area of woodless prairie of the south and east, however, finds logs far too expensive for the ordinary farmer and the house is usually made of large sun-dried brick, made of clay mixed with straw. It will perhaps be simplest to look first at one of the villages of the south and then to view briefly a small village of the Leningrad Government in the north.

Maslov Kut is a medium sized village of the county of Archangelskoe of Ter District in the North Caucasus. The county has a population of 39,000, divided among thirty-seven villages which range in size from a little more than 100 souls to more than 10,000. Maslov Kut has a population of 3,600. But it is customary to calculate in terms of the number of houses, or courtyards. In this case 750. The village lies within a mile of the railway, which is lucky, for often villages are a day's journey away from the railway, so that this is really a metropolitan luxury.

Many stories are told of the village priest going out with cross and Incense at the head of his flock in the old days to ward off the iron demon from coming too near the town. Besides, engineers who laid railway lines along arbitrary routes as indicated by Czars or shared with contractors the increased cost of laying longer lines, were not overly careful to make the most convenient stops. From the rising ground at the station the hundreds of roofs thatched with a tall, dun, river grass can be well seen lying among the locust trees.

Rising above these low one-storied cottages, the only two buildings in the town of any architectural significance stand out; the old wooden church with its inevitable five cupolas and a belfry, and the house of the former landlord, built solidly of stone and plaster after the fashion of the southern plantation mansions of the old South in the United States. Here and there, if we look closely, we may see a tiled roof, or one of tin, almost invariably painted green. These are indications of social status, a sort of brown stone front, and a girl is counted lucky indeed who marries into a house with such a cover.

If it happens to be the rainy season of fall or spring, we shall wade into the village through seas of mud. If it is midsummer, we turn our nostrils leeward and plough through a dust storm, if the wind chances to be high. There is little alternative, unless an exceptional winter brings snow. Such a village knows no sidewalks. The center of the street, having been worn deepest by traffic, provides the drainage. The German colonists a few miles distant have thrown up a carefully graded bank in front of their fences which acts as a tolerable bridge in rainy weather. When I asked one of the Germans why the Russians did not follow their example, being a good sober Mennonite he replied that the Russians were afraid they would fall off a sidewalk some- time when they were drunk and break their necks.

The houses, on closer examination, prove to be very simple structured. They are, for the most part, set immediately on the street. If the mistress is a good housekeeper, the entire outside surface of the mud brick walls will be plastered with an ill-smelling concoction of clay and manure at least once a year. When the surface is dry, it is usually whitewashed, or a bit of color, preferably blue in this district, may be added to the lime.

The simple facade of the cottage depends for its decoration on the scroll work about the windows or under the gable. These decorations show signs of once having been gaily painted, but all such luxuries have suffered during the lean years so that the general effect of the village is a drab brown. Now and then a pretentious house thrusts a portico out in front. But this is for purely decorative purposes.

The entrance is at the side of the house, through the pedestrian’s gate. Alongside this gate is the wagon entrance which leads into the courtyard. The whole yard is enclosed by a high wall, or at least a substantial fence, made either of the ever-present mud brick or of woven willow branches. Underneath the window on the street is almost invariably found some sort of bench, wooden in the case of the better-to-do families, or in other cases again of plastered mud. Here, when the weather is at all favorable the grandmother and the younger children will sit by the hour, and during the leisure periods of the evening the working members of the family gather as well, to talk with their neighbors and munch sunflower seed.

Maslov Kut lies on the higher bank of a muddy little river which rises in the Caucasus mountains and rushes down to lose itself in the sands and swamps on its way to the Caspian. Therefore the village conforms to the crooked stream rather than follows the usual principle of one long, wide main street with tributaries. But like all villages, the central place, geographically speaking, is occupied by the church.

The drunken-looking old towers were built in the time of Catherine the Great, of massive hand-hewn logs. Its architecture is one of the common types found throughout Russia, a cluster of five domes with the great one in the center rising above the other four. The belfry is a separate structure some twenty-five feet distant, connected by a cloister. The church and the little cottage of the deacon nearby are surrounded by a high burnt-brick wall, which, it is evident from the apertures for rifles, had other uses than keeping the cattle out of the churchyard. At the top of each of the two great iron gates holy pictures look calmly over the square and the pious still raise their hats and cross themselves as they pass.

Around the large square whose center is occupied by the church the principal buildings are to be found. The headquarters of the village soviet are recognized immediately by the red flag floating above the door. As a matter of fact, the flag of our village has faded to a very sickly pink, which offers a butt for discreet jokes on the part of some of the villagers.

The house is brick with a tin roof, the residence of one of the rich villagers of the old days. Beside the soviet building is the village reading room with a sort of lean-to addition to the same building set aside for an emergency jail. The medical clinic occupies another former residence on the other side of the square. The main school of the three of the village stands out in the square near the church, a symbol of the old relationship between the two institutions. The cooperative has established a branch booth in the square for the sale of tobacco and is remodeling a building, also on the square, for further extension of its business. The old master’s house, now headquarters of one of the great government farms, occupies one of the corners of the quadrangle.

The square of Maslov Kut, too, like that of all villages of any significance, has its monument to the martyrs of the Revolution, in this case a simple brick pedestal surmounted by a wooden pyramid, topped by a hammer and sickle. Near this monument all outdoor demonstrations and public speeches are staged. Many of the villages have built speaker's platforms and much more ambitious monuments.

A few blocks away the consumers cooperative has its main store, while on the corner opposite it one of the two private stores of the village flaunts itself. One block farther the producers cooperative occupies a courtyard with its buildings for grain purchasing, a small store for the supplying of agricultural needs, and various warehouses. Still farther up the street is the open space devoted to the weekly market held there every Wednesday. You may have your horse shod at the shop of the Government farm.

The shoemaker you may find by asking where he lives, if you do not know; he does not hang out his sign. For your drugs and your vodka you must go to the county seat, four miles away. Likewise, if you insist on having your clothing made away from home, you must visit the tailor there. Not even a barber’s sign decks the square and the only movie that visits the village comes for one night stands now and then to the club house of the Government Farm, which is also used as the social center of the village.

In this respect Maslov Kut is poor, for the Narodni Dom (People’s House), as the Social Center is called, is usually one of the most important buildings of the village. But there has been little building since the war and villages have thus far had to be content with the structures left them from the old regime.

One of the busiest spots in Maslov Kut is the artesian well which is also on the church square. From morning till night there waits in line a stream of peasant wagons with water barrels to be filled with this precious cargo for the distant work in the fields. Sturdy Rebeccas have beaten a path to its flow with their bare feet, balancing two heavy buckets on a yoke laid across their shoulders—a feat which I respect heartily after trying it myself. And at the rivulet where the abundant fountain flows off to irrigate the gardens that lie nearby, housewives beat out the linen of the family wash. I have many times seen the washing done through a hole in the ice in the villages of the north.

Such is Maslov Kut and, in general, all her neighbors as seen by the casual visitor. Not beautiful nor picturesque, unless seen at a distance with the outlines of the church domes soaring above the dull level of the cottages, and then best on a rosy morning when the smoke is rising from the kitchen fires and curling lazily above treetops. The thousands of other villages that dot the great woodless plains of the south and east differ only in details.

The larger villages, which are usually also county administrative centers, will have more stores and a number of barbers, photographers, bootmakers and the like will hang out their signs. This is particularly true of the villages with well attended markets, whose weekly crowds from all the surrounding villages offer possible customers. And except for one or two, of the distinctly Soviet signs of occupancy, the .same picture might have been drawn a hundred years ago.

Borders, Karl. Village Life Under the Soviets. Vanguard Printings, 1927.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.