Methods of Capturing Animals

The first run of salmon occurs about the middle of July, when they swarm in myriads into the mouths of the small fresh-water streams. It is difficult to picture in…

From: Unknown To: 1890 C.E.

Location: Haida Gwaii, British Columbia, Canada; Prince of Wales Island, Alaska, United States of America

Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From The Coast Indians of Southern Alaska and Northern British Columbia by Albert P. Niblack, 1890.

Salmon

The first run of salmon occurs about the middle of July, when they swarm in myriads into the mouths of the small fresh-water streams. It is difficult to picture in the mind the abundance of these fish and the mad abandon with which the hurl themselves over obstacles, wounded, panting, often baffled, but always eagerly pressing on up the streams there to spawn and die.

In some of the pools they gather in such numbers as to almost solidly pack the surface. When there is a waterfall barring their progress they may be seen leaping at the fall endeavoring to ascend it, often as many as six or more being in the air at once.

The flesh at first hard and firm on contact with fresh water soon loses its color and palatableness, so that the sooner they are captured the better. The species of the first run vary along the coast. They are comparatively small, do not remain long, and do not furnish the bulk of the supply, although at the canneries now erected as many as two to five thousand have been known to be caught with one haul of the largest seines.

“The Raven and the Fisherman.” Images from text, by Albert P. Niblack, 1890.

About the middle of August the Tyee or King salmon arrives, the run often lasting the year out.

When they first appear they are fat, beautifully colored, and full of life and animation; but soon are terribly bruised, their skin becomes pale, their snouts hook-shaped, their bodies lean and emaciated, and their flesh soft, pale, and unwholesome.

In Wrangell Narrows is a waterfall of about 13 feet. At high tide the salt water backs up the stream and reduces this fall to about 8 feet, but neverless even at spring tides, but the King salmon leaps the falls and numbers of them may be found in the fresh water above. The writer has deposited in the Smithsonian Institution several instantaneous photographs of leaping salmon taken by himself at this locality, but it is unnecessary to reproduce them iii this connection.

The whole of the territory on the northwest coast adjacent to the Indian villages is portioned out amongst the different families or households as hunting, fishing, and berrying grounds, and handed down from generation to generation and recognized as personal property. Privilege for an Indian, other than the owner, to hunt, fish, or gather berries can only be secured by payment.

Each stream has its owner, whose summer camp, often of a permanent nature, can be seen where the salmon run in greatest abundance. Often such streams are held in severalty by two or more families with equal privileges of fishing.

Salmon are never caught on a hook; this method, if practicable at all, being too slow. At the mouth of the streams they are speared or caught in nets. High up the streams they are trapped in weirs and either speared or dipped out with dip-nets. The Indians are beginning now to use seines and to work for salmon on shares, but the older ones are very conservative, and cling somewhat to primitive methods in a matter even so important to them as the capture of salmon, their chief food supply.

Albert P. Niblack, 1890.

Halibut

These may be taken at almost any season in certain localities, while they are more numerous during certain months in others. The Indians make the subject quite a study, and know just where all the banks are and at what seasons it is best to fish.

Often villages are located on exposed sites for no other reason than to be near certain halibut grounds. This fish varies in size from 20 to 120 pounds, and is caught only with a hook and line. The type of hook is that shown in Plate XXXI, and the method of sinking it shown in Plate XXX, Fig. 151. This fish stays close along the bottom, and is such a greedy feeder as to be readily caught by the clumsy hook shown.

In fishing for halibut the canoe is anchored by means of stones and cedar bark ropes. The bait is lashed to the hook, a stone sinker attached to the line, and the contrivance lowered to the bottom. Sometimes the upper ends of the lines are attached to floats and more than one line tended at a time.

A fish being hooked is hauled up, played for a while, drawn alongside, grappled, and finally despatched with blows of a club carried for the purpose. It requires no little skill to land a hundred-pound halibut in a light fishing canoe. A primitive halibut fishing outfit consists of kelp-lines, wooden floats, stone sinkers, an anchor line, a wooden club, and wooden fish hooks. It is impossible with our most modern appliances to compete with the Indians in halibut fishing. With their crude implements they meet with the most surprising success.

Herring and eulachon

Herring are found in the summer months in numerous parts of the coast, depending on the nature of the feeding ground. They run in large shoals, breaking the surface of the water, and attracting in their wake other fish, porpoises, whales, whale “killers,” flights of eagles, and flocks of surf birds, all feeding either on the herring or on the same food as that of which they themselves are in search.

They are dipped out by the Indians with nets or baskets, caught with drag-nets, or taken with the rakes previously described. Eulachon or “candle-fish” run only in the mouths of rivers,particularly the Skeena, Nass, and Stikine in this region. They are considered great delicacies, and are dried and traded up and down the coast by the Indians who are fortunate enough to control the season’s catch.

Cod are caught with the skil hook previously described. Dogfish, flounders, and other kinds are caught with almost any kind of hook, there being no especial appliances used or required.

Spawn

For taking fish eggs that have already been spawned, the Indians use the branches of the pine tree, stuck in the muddy bottom, to which it readily adheres, and on which it is afterwards dried. When dry it is stripped from the branches and stored in baskets or boxes; sometimes buried in the ground. The spawn gets a pleasing flavor from the pine. Roe is taken from captured fish and either dried or buried in the ground to become rank enough to suit the epicurean palate of the Indian gourmand.

Sea otter

The custom in former days was to hunt the sea-otter either from the shore or in canoe parties. They were shot with arrows from behind screens when they landed to bask on the sand or on the rocks, or approached noiselessly by canoe parties when asleep on the water.

Very thin light paddles were used, and if the Indian could get near enough the sleeping animal was harpooned. The common custom was, however, to hunt in parties. An otter being sighted was surrounded by canoes in a very large but gradually lessening circle, advantage being taken of the necessity of the animal to come to the surface to breathe, when it would be shot with arrows or harpooned from the nearest canoe.

The Tlingit and Haida were not so expert as the Aleut, because their canoes were not so well adapted to the exposure at sea. In recent years the few remaining sea-otters have been hunted with fire-arms. The Indians are poor marksmen, and under the excitement of firing the instant the otter rises many accidents to their own number have happened, particularly to those on opposite sides of the circle. By a curious rule the otter, and all other game, belongs to the one who first wounds it, no matter who kills it.

As the otter floats when killed, the same skill is not required as in seal hunting, but so scarce have they become now, that not more than forty or fifty are killed in a season throughout the northern coast Indian region.

Seals

Seals are hunted in practically the same way as just described, but from the fact that on account of their bodies not floating it is necessary to harpoon them before they sink, the percentage of loss is very large, although they are more abundant than the otter. The Indians rely to a great extent on shooting them in very shallow water or on rocky ledges near shore.

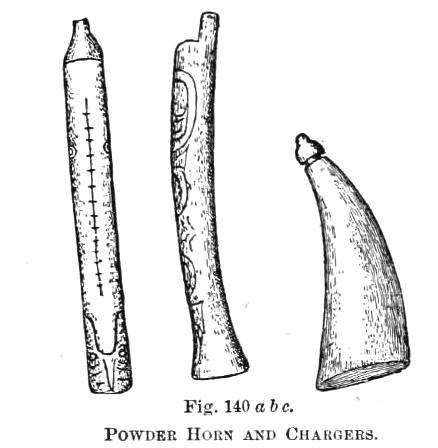

On shore the Indians are very poor still-hunters, and luck and abundance of game are large elements in their success. Fur-bearing animals, such as bear, lynx, land otter, beaver, etc., are generally trapped, although shot whenever chance otters. Breech-loading arms are not allowed to be sold to the Indians. With the use of muzzle loaders we find such necessaries in the outfit of a hunter as Figs. 140a and 140b, which are powder chargers of bone, and Fig. 140c, which is a percussion-cap box made from the horn of a mountain goat.

Albert P. Niblack, 1890.

Deer

Deer are very abundant, and form a large item in the food supply of the region. They are hunted in the rutting season with a call, which lures them to the ambushed hunter, when they are readily shot. So effective is this call, that it is not unusual to be able to get a second shot at them in case of first failure. Still hunting is very little resorted to, and an Indian seldom risks wasting a charge until he is somewhat sure of his distance and chances. They are often captured swimming, and in winter recklessly slaughtered for their hides when driven down to the shore by heavy and long-continued snows. The deer-call is made from a blade of grass placed between two strips of wood, and is a very clever imitation of the cry of a deer in the rutting season. The wolves play great havoc in this region with the deer, and it seems remarkable that they exist in such numbers with so many ruthless enemies.

Mountain goats and sheep

On the mainland these are shot with very little difficulty if one can overcome the natural obstacles to reaching the lofty heights which they frequent.

Bears

The brown and black bear are the two species quite generally found in Alaska. Both are hunted with dogs, shot when accidentally encountered, or trapped with dead-falls.

The brown bear (Ursus Richardsonii) is from 6 to 12 feet long and fully as ferocious as the grizzly. The hair is coarse, and the skins, not bringing a good price, are generally kept by the Indians for bedding. This fact, coupled with the natural ferocity of this species, has led to the brown bear being generally let alone.

An accidental meeting in the woods with one of them is regarded as a very disagreeable incident by an Indian. When women and children run across bear-tracks in the woods, in deference to a generally recognized superstition, they immediately say the most charmingly complimentary things of bears in general and this visitor in particular. Petroff gives the origin of this custom as follows:

“The bear was formerly rarely hunted by the superstitious Thlinkit, who had been told by the shamans that it is a man who has assumed the shape of an animal. They have a tradition to the effect that this secret of nature first became known through the daughter of a chief who came in contact with a man transformed into a bear. The woman in question went into the woods to gather berries, and incautiously spoke in terms of ridicule of the bear, whose traces she observed in the path. In punishment for her levity she was decoyed into the bear’s lair and there compelled to marry him and assume the form of a bear. After her husband and her ursine child had been killed by her Thlinkit brethren, she returned to her home in her former shape and narrated her adventures.”

This legend is found in other forms throughout the coast, and occasion will be taken in another chapter to comment on it further. In conclusion, it may be said that the brown bear are expert fishers and frequent the streams in the salmon season along their well-beaten tracks, which form the best paths through the woods.

The black bear (Ursus americanus) is, on the other hand, rather timid and eagerly hunted, not only for his valuable black skin, but for his flesh, which, when young and tender, is very palatable. In the spring they are readily killed along the edge of the woods, when they come out to feed on the first sprigs of skunk-cabbage and other plants brought out by the warm sun. Later in the summer they are found along the streams, where they feed on the dead and dying salmon.

Taking it altogether, the Indians are expert fishermen but poor hunters, indifferent marksmen, and wanting in that coolness and nerve for which the hunting Indians of the interior are famous.

Besides the animals hunted for their skins as mentioned, there may be added the fox, wolf, mink, marten, land-otter, and an occasional Canada lynx and wolverine on the mainland. The method of dressing the skin is not different from that of the interior Indians, so generally described in works of travel. The skin scrapers or dressers are either of stone or bone, and of the pattern shown in Fig. 79h, Plate XX and Fig. 79k.

Ermine and marmot

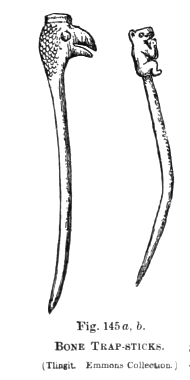

In Figs. 145a and 145b are shown two bone trap sticks, to which are fastened the sinew nooses used in the capture of ermine and marmot. Those for ermine are somewhat smaller than those shown in the figure. They are, moreover, sometimes made of wood instead of bone, and are elaborately carved in totemic designs. These two specimens are from the Emmons collection.

Albert P. Niblack. The Coast Indians of Southern Alaska and Northern British Columbia. US National Museum. 1890.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.