Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Primitive Economics of the New Zealand Maori by Raymond Firth, 1929.

Social Relations in the Village

In the discussion of the two great rallying points of village life, the public square and the meeting-house, the community has been treated rather as if it were an undifferentiated body, acting in group unanimity. The analysis of the social organization must now be carried further, to show the type of units which composed the village, and the nature of the social stratification.

The Maori village comprised a number of households, each centring its activities around a dwelling-hut. These were mainly used for sleeping or resting in bad weather, since no cooking could be done or meals taken within them, and economic tasks were better performed outside. Nevertheless to a certain group of people the dwelling-house represented their home. Usually each hut was occupied by a single family; often, however, it was shared by a larger group of relatives, in which case each little group of parents and children usually occupied its own corner of the dwelling. But no partition of any kind was ever raised and great freedom was observed.

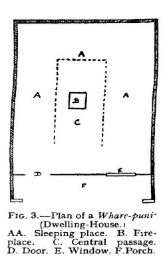

Figure 3 shows the plan of such a dwelling-house, of the whare-puni type. Modem examples are shown in Plate VI The door and window were both small, and the interior fittings very simple. A space of bare earth ran down the middle of the hut, with a stone fireplace in the centre. Small timbers or a line of stones set on edge marked off a sleeping place on either side and sometimes at the back also. Bracken was spread to soften the hardness of Mother Earth, and mats were laid over the top. Guests slept near the window as in the houses of superior style.

Other furniture was practically absent from the hut. A flax cord or a pole stretched across a comer allowed small objects to be hung up temporarily, but cooking utensils were kept in a shed near the ovens, and tools were stored in a hut on posts or in a shed. Eating dishes were freshly made for each meal and then thrown away.

To each household belonged a few store pits for root crops, a plain hut on posts for preserved foods and gear of all kinds, and an oven or two in the cooking shed. A few sleeping mats, some utensils, such as water gourds, bark containers, flax kits, and the like completed the tale of immediate household belongings. Chiefs, of course, had more property than other men, but this consisted in ornaments, fine garments, and large stores of food rather than in any more ostentatious furnishing of the dwelling-house. There were no overwhelming property distinctions in Maori society.

The social stratification within the community was fairly simple in its fundamental principles. Theoretically there may be said to have been three classes of people in Maori society: chiefs, commoners, and slaves. But to understand the many shades of social differentiation a closer analysis of the exact content of each term is necessary.

With the chiefs, a distinction must be drawn between ariki and rangatira. The ariki was a high-born chief, a descendant of first-born children in a continuous elder line, or to adopt Best’s definition, “a first-born male or female of a leading family of a tribe.” The rangatira were the ”gentlemen”, junior relatives of the ariki.

The terms tumu whakarae, poutangata, pouwhenua, and the like, sometimes said to indicate a class of persons of superior standing to ariki, were in reality honorific terms for such chiefs in one capacity or another.

The commoners were people of low social standing, due to such causes as consistent descent from younger members of junior branches of a family—younger sons of younger sons ad infinitum—intermarriage of people of low rank with slaves, or loss of prestige, as being the offspring of persons redeemed from slavery. In its essential nature the social stratification is coincident with the general principle of Maori grouping, that of descent from common ancestors.

For, given the value attached to primogeniture, since all members of a group trace their ancestry back to the same forbear, the main differences in rank emerge naturally from the order of birth. Especial social prestige attached to priests, wizards who practised black magic, and the teachers of traditional lore, whose status depended upon their training rather than upon their birth—though they were generally drawn from chiefly families.

Tattooers, carvers, and experts in various branches of economic activity also gained social position by reason of their skill, as did famous warriors. But these persons did not constitute distinct social classes, such as were created by status of birth. The term tohunga, properly applicable to an expert in any branch of knowledge, was in no way a class badge, as has been sometimes suggested.

It has been maintained, with a certain point, that Maori society comprised only two classes, rangatira and slaves, since all free members of the tribe were related in some degree to chiefs of rank, and could therefore consider themselves gentlemen. Best remarks that during his long contact with the Maori he has never found a person who would admit that he belonged to the class of commoners!

A man of Ngatimanunui once modestly denied to the present writer that he was a rangatira, but in modem speech this term is often used with the distinctive meaning of actual chief, and he was understood in this sense.

The social differentiation between chiefs and men of lesser rank was not marked by any exaggerated forms of respect. No commoner crouched or made obeisance before a chief, nor were any special titles or terms of respect used in addressing him in ordinary conversation, beyond those prescribed by etiquette as due to married people or aged persons.

A very independent spirit obtained in the contacts of everyday village life. The special position of a chief was seen in the weight of his opinion when expressed at public gatherings, his trained proficiency as an orator, his knowledge of genealogies, proverbs, and songs, his assumption of leadership in war and in economic undertakings, the greater amount of ceremonial pertaining to his birth, marriage, and death, and his observance of a much stricter system of tapu.

Eminence of birth alone, however, was not the sole passport to rank and influence. As a chief, practical qualities of decision of character, foresight, initiative, and ability were required as well. When these were not apparent in the first-born son, then the leadership of the tribe would pass over him and be vested in his younger brother, if capable, or failing him in the nearest male cousin, as a rule patrilineal, but in default, of matrilineal connexion, most fitted to command. But in religious and ceremonial affairs the ariki still played his part. Some examples given me by Mr. Geo. Graham in a most interesting communication illustrate this point very clearly.

Te Hira was by birth the hereditary chief of Te Taou hapu of Ngatiwhatua, but neither he nor his brother were men of force of character. Hence their father passed his mana (authority) on to Paora Tuhaere, his nephew. To this man the Ngatiwhatua of that hapu looked for guidance, and he was their recognized political head, restrained them from participating in the “King” movement, and conducted the affairs of the people to the time of his death.

But Hira still retained the prestige of birth and could not be deprived of his status of ariki, the lineal heir. In certain magical and ceremonial performances, he and he only could officiate.

Thus for the imposing and lifting of tapu, the carrying out of ritual observances as at the birth of children, hair cutting, the fixing of boundary marks, defining tribal territory, recital of curative magic and the like, no one else could take his place. The reception of visitors, speech-making on state occasions, as for the tribe as a whole, the recital of genealogies, and the giving and receiving of presents were all the privileges of Te Hira.

To him again belonged the right of bestowing names on children, and of asking for female children of other tribes as the betrothed wives for the young men of his own people. With him rested the guardianship of the tribal taonga (heirlooms) and the mauri (talismans) of fisheries and forests. All this centred around him as the ariki.

The eldest in descent, though deprived by incompetence of his authority as leader of the tribe, always retained his mana ariki—his prestige as the first-born son, and certain associated privileges of a ritual or ceremonial nature. Moreover, the son or later descendant of the ariki might again recover the political and social status of his less competent father or grandsire, and so once more unite in his person the exoteric as well as the esoteric mana of chieftainship.

This division of the powers of the ariki in the somewhat rare cases of incompetence, to allow of a secular as well as a temporal head, secured the efficient government of the tribe. The Maori, despite his reverence for primo-geniture, has a sane outlook in such matters; he does not blindly allow the fortunes of the tribe to be sacrificed to the lack of ability of the lineal chieftain.

A chief who led his tribe by virtue of authority gained by ability or force of character as distinct from birth, is always recognized as holding his position in such a capacity. He is known as a rangatira paraparau. Such were Paora Tuhaere and the renowned Te Rauparaha.

The main points of the story of how the latter gained his authority are well known, but the version given by Mr. Graham is worthy of mention here.

All Ngatitoa were assembled to hear the poroporoaki (last words) of their dying chief Hapi Tuarangi, a famous warrior who had ably led his people for many years. The problem of his successor was an anxious one, for the situation of the tribe was perilous, and only a man of great courage, self-confidence, and political wisdom could hope to guide its destinies. So it befel that none of the near relatives of the dying chief were willing to undertake the heavy responsibility, and only Te Rauparaha, then a mere youth, responded to the call. “Who after me will lead my tribe?'' was the momentous question of the old man. After some minutes' silence, when neither the sons nor elder nephews replied, Rau stood up at the far end of the village marae and called out, "E koro, ko au tonu—Ka mate atu he tete kura, ka ara ano he tete kura.“ O, Sire—I indeed will do so—for as the carved stern-post of the canoe passes into decay, still another such carved stern-post will arise.

That is, the tribe (canoe) would not be without its necessary leadership and dignity. The tete kura is ceremonially the most important part of the canoe: from its mana the canoe derives its speed, sea-worthiness, and general efficacy. Hence the simile of Te Rauparaha—he would be the tete kura to replace that which was being destroyed by death. When the stern-post of a canoe became decayed or broken, another took its place—even so with the chiefs of the tribe. Such was the word of Te Rauparaha in reply to the question of the dying ariki, which gained him the leadership of the tribe, a position which his ability, force of character, and enterprise enabled him to hold firm.

As a rule a chief nominated his successor before death, and this was ratified by the approval of the assembled people, given not loudly and with one voice, but by silence or small sounds of assent, as of a slight cough running round the gathering. The eldest son of the deceased chief, if a man of proved ability, often assumed his father's place without formal acknowledgment, but the tacit acceptance of the people, as shown in their obedience to his wishes, was needed as an endorsement of his position and authority.

One mark of a chief was generally the number of slaves he had in his household. Slavery was a definite and useful institution among the Maori, and prisoners taken in war comprised the main part of the people in this category. There was no static slave class, since the women, especially, intermarried with free people of low rank, and the resulting offspring were free. Slave girls, too, were often taken as concubines or secondary wives by chiefs, and the children, though they always bore the stigma of their parenthood, could freely wield power and influence.

Slaves were not general tribal property, but always belonged to individual owners. On the whole, the relations between them and their masters were easy and pleasant. The slaves did the menial work, but were well fed and housed. Though without the protection of any specific social rules, being at the mercy of the anger of their master, and liable to be called upon for a human sacrifice or to provide a relish to a feast, on the average they were well treated. But the statement of William Brown that slaves frequently possessed land which was freely distributed among them by their master, whose interest lay in conciliating their goodwill, is quite wide of the truth. A Maori slave, not being a member of the tribe, could never possess land, and it is to be doubted if, except in rare instances, he could cultivate for himself a piece of ground allotted to him by his owner.

A hint has now been given of certain of the principles which determined social relations within the village, but there are still further aspects to be developed.

Firth, Raymond. Primitive Economics of the New Zealand Maori. George Routledge & Sons, 1929.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.