Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

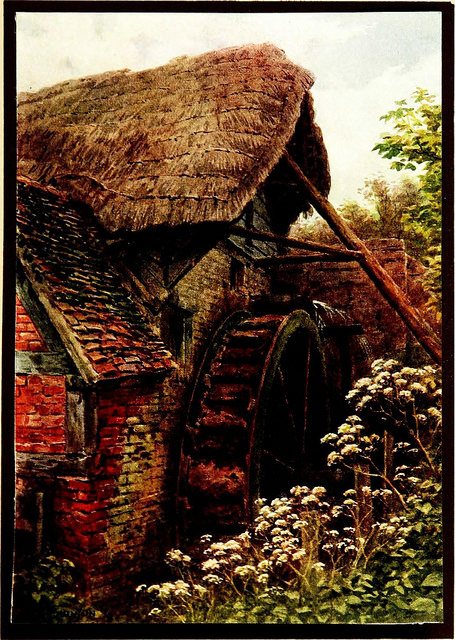

“The Cot by the Wayside,” from The Cottages and the Village Life of Rural England by Peter Hampson Ditchfield, 1912.

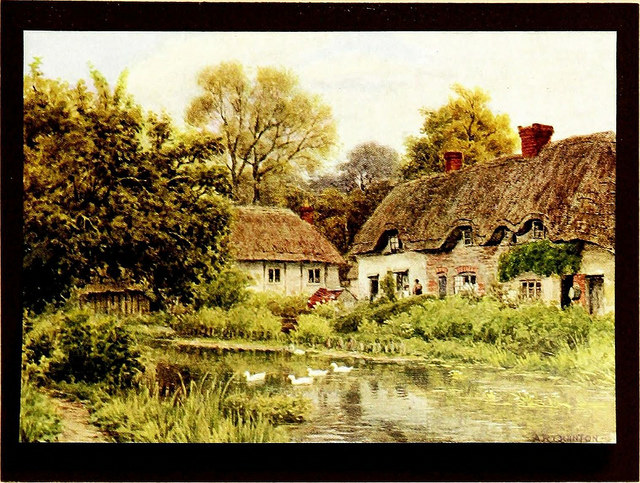

The appreciation of cottage-building is a plant of recent growth, a newly found truth, and, therefore, precious. The cottage has a beauty that is all its own, a directness, a simplicity, a variety and an inevitable quality. The intimate way in which cottages ally themselves with the soil and blend with the ever-varied and exquisite landscape, the delicate harmonies that grow from their gentle relationship with their surroundings, the modulation from man’s handiwork to God’s enveloping world that binds one to the other without discord or dissonance—all this is a revelation to eyes unaccustomed to seek out the secrets of art and nature.

“It is only a cottage,” people say, without realising the importance which it really occupies in the story of English building, apart from the fact that they are very picturesque and very beautiful. They are that—at least we think so now, when we are delivered from the old regime of artificiality and false standards passed away in the last century, and new ideals, which were really a revival of the old, taught us sounder principles of taste.

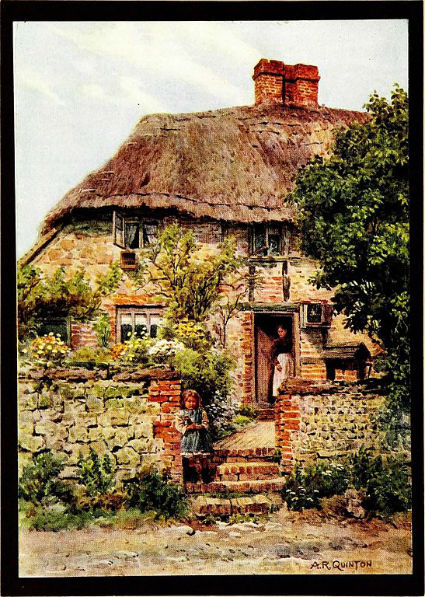

It would be hard to exaggerate the value of these little English cottages from this aspect of beauty alone. No one can deny that Bignor is a quiet agricultural village, and not the least interesting of its specimens of domestic architecture is this charming old cottage. It is built in three bays, the central one receding, the roof over it being supported by curved braces. The oblong openings between the upright and horizontal timbers have been filled with bricks when the old wattle and daub decayed, and these are arranged in herring-bone fashion. The two external bays have an over-sailing upper storey supported upon imposts.

The foundations of the house are built of local stone, and the doors are set above this where the timber-work begins, and are reached by a graceful flight of steps protected by a hand-rail. The windows are of lattice-work, and the roof of thatch wrought with spars to keep it in its place. the period of the decline and fall of English architecture had reached its lowest depth in the early nineteenth century. It could sink no lower, and then there dawned upon eyes that had somehow recovered their sight and could appreciate what they saw a glimpse of a typical English cottage. It was like finding amidst dust and cobwebs a precious mediaeval manuscript bright with the illuminations of the old monks; or a grand fourteenth-century walled-up window amid the vanities of Strawberry Hill Gothic.

Cottage-building is neither Gothic nor Classic; it is just good, sound, genuine and instructive English work, and when we can appreciate that we can learn to build the lofty minster or the mansion in a style of which no one need be ashamed. One other note we must make before we turn over the pages of our pictures and admire their beauties; and that is this. The great era of architectural triumphs came to an end in the fifteenth century. The building of minsters and parish churches ceased entirely; the erection of mansions and manor-houses proceeded at first with conspicuous success in the reigns of Elizabeth and James I., but the art rapidly declined and sank swiftly in the dark days of the later eighteenth century.

But all the time the poor and middle classes were building, quietly and simply, untroubled by any controversies concerning the relative advantages of Renaissance or Gothic styles. They built for use, and carried on the traditions of their fathers and forefathers, frankly, simply, and directly; and it is this that makes their buildings valuable to us. They have preserved for us the laws and traditions and records of a time that has passed away; and if we would regain what we have lost we must study the relics that time has spared us, and without slavishly imitating, as Horace Walpole copied his ruined abbeys, build in the spirit which produced such excellent work.

But what is a cottage? If we search the dry and musty tomes of English law books we find that, according to a statute of K. Edward I., a cottage is a house with any land attached to it. It can date its pedigree back earlier than that. The cottarii or bordarii of the Domesday Survey were cottagers, those who dwelt in cots or cottages, were freemen, but were obliged to do some fixed services for the lord of the manor, and could not leave his estate to work elsewhere. When in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries the English wool trade was most prosperous, and landlords turned their agricultural land into sheep-runs, fewer labourers were required and there was a great destruction of cottages.

In the reign of Henry VII., in A.D. 1489, it was found necessary to pass an Act of Parliament prohibiting the wholesale pulling down of farms and cottages. Moreover, labourers used to sleep in their employer’s house and have their meals in the hall with the family, though at a separate table.

But in the time of Queen Elizabeth cottages were again required, and were then re-erected. An Act of her reign tells of the building of many such dwellings, as its object was “for avoiding of the great inconveniences which are found by experience to grow by the erectinge and buyldinge of great nombers and multitude of cottages which are dayly more and more increased in mayni parts of this realm.” It orders that no one is to build or convert dwellings into cottages without setting apart at least four acres of ground to each. It excepts from the rule towns, mines, factories, and cottages for seafaring folk, under-keepers, and the like. In this provision the order anticipates the modern dream of beneficent legislation of “three acres and a cow.”

We gather from this that in the days of Queen Elizabeth cottage-building was vastly increased, and that old farmhouses and other buildings, as they fell into disuse owing to the erection of newer and more commodious houses, were converted into cottages for the accommodation of the increased number of agricultural labourers.

Then arose some of those beautiful rural homes which are still with us, and many examples are set forth in these pages. Some have the curse of poverty stamped upon them, and I would distinguish a cottage from a hovel—a small space enclosed by four mud walls and covered with sheltering thatch—as well as from one of those absurd lodges with Corinthian pillars and pseudo-Gothic windows erected on some estates in a period of debased taste. The English cottage rejects the poverty of the hovel, as well as the frippery decorations of “ the grand style.”

“Houses are built to live in and not to look upon,” sagely remarks Lord Bacon; “therefore let Use be preferred before Uniformity, except where both may be had.” The builders of the sixteenth century were not unaware of this principle, and acted on it, though in seeking utility they achieved wonders in the way of beauty.

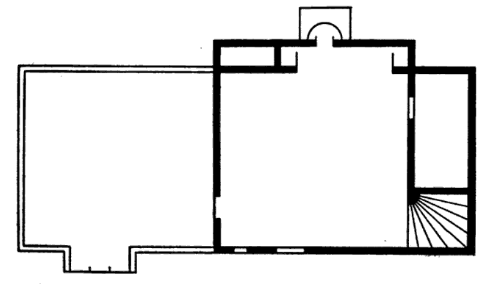

Before we examine the various styles and materials used in the construction of our cottage homes, which depend upon the geological features of the districts where they were built, it may be well to discover their plan. This is very similar in all parts of the country. The simplest plan is an oblong with two storeys, subsequent additions having usually been made. The above plan is not an uncommon one. The part enclosed in unblacked lines is an early addition. You will observe the central chamber with large wide fireplace and ingle-nook, the larder, and staircase in one corner with stairs formed round a newel.

After the date 1600, straight stairs came into fashion, and were often formed by cutting steps in a solid balk of oak. You will notice the oven at the back of the fireplace. This is often of later date, as cottagers probably in olden days baked their bread in the baking-ovens attached to their employers’ houses. Moreover, village bakers plied their trade as they do now. But in the sixteenth century and later the cottagers found it more economical to make these useful additions to rural abodes. They are sometimes quite large, and I knew a man who used to make an old oven his bed-chamber, though happily for him the fire was not lighted. In many cottages the large fireplace and ingle-nook have been bricked up. The modern labourer’s wife wants a kitchen range and likes not the primitive style of cookery. Hence the old ingle-nooks have vanished and the fireplace fitted with less snug but more convenient modern culinary appliances.

Gone, too, are the iron fire-dogs which gave a draught to the wood fire, and carried two loose square iron bars for the support of the cooking-pot. Sometimes there was a branched top to the iron dog for holding a cup of hot spiced ale, which was grateful and comforting on a cold winter’s evening. The old methods of cooking were not to be despised. Joints were roasted on spits, either a large basket one for holding a joint of beef, or one with prongs, and to these was attached a wheel which was turned by a smoke-jack in the chimney.

But we must build our cottage before we examine the details of its domestic economy. The charming cottage at Bignor, in Sussex, a county of delightful homesteads, is built in three bays, the central one receding, the roof of which is supported by curved braces. It is a half-timbered house, like most of those depicted by our artist, who has a penchant for that method of construction. The oblong openings between the perpendicular and horizontal timbers are filled in with wattle and daub, and, where this has become decayed, with bricks, and these are arranged in herring-bone fashion, which method of building has come down to us from Saxon times, stone herring-bone work being usually deemed a peculiarity of Anglo-Saxon construction.

But it must be noticed that this, and many similar houses, were built in bays, “the simplest form of construction being the house of one bay. Two pairs of bent trees (whence the term ‘roof-tree’ seems to have been derived) were set up about sixteen feet apart. The gable end of many an old Cheshire cottage shows the persistence of this traditional type.”

In Yorkshire and in other parts of England it is not uncommon to find the stables, barn, and dwelling-house all under the same roof and in one line. Hence each part of the structure corresponded in length to that which was required for the plough-team of two pairs of oxen. A survey of the estates of the Earl of Arundel records “a dwelling house of four bayes a stable being an outshut and other outhouses are seven bayes besides a bame of four bayes.”

Shakespeare may be quoted as a witness of this when he makes Pompey say in “Measure for Measure.” If this law hold in Vienna ten year, I’ll rent the fairest house in it after threepence a bay.”

That Bignor cottage, formerly the dwelling of a yeoman, and now a village shop, which we have so much admired, and serves to illustrate this story of the bays, reminds us of other interesting things that the village contains. These are—not the bays—the wondrous yews in the churchyard. We have been told that yews were grown in churchyards for the furnishing of bows for our English archers, who struck terror into the hearts of the French and won fame on many a foreign battlefield. But we think that the yew-tree is there for a sacred and symbolical reason, signifying the Resurrection.

However that may be, there they grow venerable yet flourishing nigh Bignor Church; and not only does the village contain the remains of one of the most perfect Roman villas in England, with beautiful mosaic pavements, but—more nearly connected with our present subject—in the above-mentioned cottage, the quaintest and most curious little rural shop in the county. It is nigh the church, and there it stands with its diamond-paned windows, oak timbers, crazy doorway and approach by a flight of steep steps, a venerable relic of antiquity which we trust Bignor will long preserve.

But revenons a nos moutons, or rather to cottage architecture. The earliest cottages were built in the shape of an inverted boat. Two pairs of forks were set out at distances of a bay apart, and then beams or boards stretched across, and covered with thatch, the covering extending to the ground. Walls were an afterthought. We are so accustomed to having walls to our houses, and the roof resting on them, that we can hardly understand this primitive style of dwelling, which resembled a boat turned upside down.

There are only two houses of this kind that remain, as far as we are aware; one at Scrivelsby, in Lincolnshire, vulgarly known as “Tea-pot Hall,” and the other at Didcot, in Berkshire. Such cottages resemble booths or tents, and were evidently based upon that model. There is a so-called oratory of Gallerius near Dingle, in the West of Ireland, built of stone, of similar shape. A remembrance of this boat-like shaped building is preserved in our word “nave,” as of a church, which is the Latin navis, a ship.

We have so much to tell of Rural England that it is impossible for us here to trace the gradual development of our cottage architecture, and to show how the forked-shaped buildings took to themselves walls, still preserving the forked basis of construction. We have seen how a new era of cottage-building started in Elizabeth’s time; and it will be sufficient for our present purpose if we take that reign as a starting-point for a beginning of the story of the humbler form of domestic architecture. We see the cottages to-day that often date their foundation from that period. We admire their beauties. Perhaps it may be well to understand why we admire them, in what their merit consists; and so enable ourselves to appreciate more fully their charming character.

The commonest form of cottage of the better sort erected during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is that framed after the model of the manor-house. Everyone is familiar with the story of the development of the English manor-house, a story that I have already told and need not here repeat. The cottages followed the same plan, as several of our illustrations show. There is an L-shaped cottage at Carhampton, to which we have already referred. Cowdray’s Cottage is based upon the same plan. In the village street of Kersey there is an H-shaped house, and the view of East Hagbourne shows another example of the L-shaped cottage. At Steventon there is an E-planned house.

Possibly some of the cottage homes here depicted have seen better days, and were originally substantial farmhouses, now converted into cottages. They do not always make the best rural homes. The neighbours are too near together. Sometimes they quarrel and “do not speak”; and relations become strained when there is a common pump, and both housewives want to draw water at the same time, and children will trespass sometimes, and look over a neighbour’s fence, if not pick flowers just on the other side. Peace does not always reign when tempers are ruffled, and though proximity often brings love, it sometimes fosters dislike, and affairs do not run smoothly. It is, however, interesting to notice the continuance of tradition in the planning and evolving of cottage architecture.

Another plan of cottage-building is the squatter’s cottage, a very simple and homely structure. You will have noticed in many villages along the side of the road with gardens touching the hedge of the fields little cottages built on land that has been an encroachment. There are several houses of this description in my parish of Barkham. Country roads were wide; they were repaired and gravelled. The ruts were deep and the way almost impassable, just like the green lanes in this village, along which if you ride your horse’s hoofs stick so fast that you are afraid lest he will leave one behind him. So the carters drove whither they listed along this wide track.

Gipsies pitched their tents on this disused land. No one thought it of any value, and then the squatter came and reared his simple dwelling of two rooms and covered it with thatch. He chose the materials that came readiest to his hand, bricks or cob, stone or timber, which his employer carted for him. Most of the work he did himself with the help of a kindly neighbour; and then he would raise a bank and enclose a small garden, and plant a hedge of elders because they grow quickly. And thus he became a miniature landowner, paying no rent, perhaps a small due to the lord of the manor for a few years, but was practically his own landlord and ruler of his own little domain. He becomes very proud of his cottage, and proud of himself, and develops into a sturdy and independent person, one of the best of labourers, happy and contented.

Ditchield, Peter. The Cottages and the Village Life of Rural England. E.P. Dutton & Co. 1912.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.