Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From When I Was a Boy in Ireland, by Alan Michael Buck, 1936.

The history of Ireland is sad history over which in boyhood I many times cried. It is sad because for hundreds of years Ireland was looked upon by England’s kings as a vast and beautiful estate to be cut up and divided among their court favorites, and for as many years England’s kings looked upon the Irish people as slaves to serve their court favorites.

But Ireland has a proud spirit, a spirit which never has nor ever will be broken. Time and time again down through the years, the people of Ireland have rebelled against British rule. Time and time again the people of Ireland have been on the verge of regaining their freedom but always at the last something unforeseen has happened to spoil their plans.

As a boy I lived through two such rebellions. The first of these was the rebellion of 1916. I barely recall it, being very young then. Mother and Father, of course, were interested in its every phase and I do recall their tears when they learned that Sir Roger Casement, on returning from the continent where he had made arrangements for the ammunition supply for the rebellion, had been arrested, taken to Britain and there executed as a traitor to the Crown.

Despite Sir Roger Casement’s capture, however, the rebellion grew under the leadership of Padraic Pearse and in Easter week it broke out. It broke out in Dublin and was expected to spread throughout the length and breadth of the country. But it did not spread because the people were not united and because it did not spread, it failed. For England, engaged in war with Germany though she was, it was an easy matter to send soldiers to stifle the rebellion at its root in Dublin. The soldiers arrived. They cornered the ‘‘rebels.” To prison they took them. Later they shot them. The names of the dead are forever engraved on every Irish heart. Among them are such valiant men as Thomas Clarke whose sons, Thomas and Emmet, were my schoolmates, Padraic Pearse and James Connolly, who, because of his wounds, had to be carried out from his cell and seated in a chair against the prison wall where he was shot to death.

The rebellion of 1922 and the years of its growth, I recall more clearly. Little pictures of it flash before me like lantern slides, clear in every detail. I will put them into words for you.

One morning at breakfast. Father read to us from the paper that England had opened her jails, clothed her convicts in black uniforms and tan boots and then was shipping them to Ireland to terrorize us.

“Now what do you know about that?” said Father, a hard look to his mouth.

Several days later, I remember Father drawing up a list of the people in the house so that the “Black and Tans” when they raided us might compare it with the number of people on hand at the time. Well, we knew if more people were present and our explanation did not ring true, we would be shot even as others already had been shot, and our house burned to the ground.

Bobby, Terence Smith and I left Waterford by train for Mount Saint Benedict. In the carriage with us was a venerable, white bearded, old man. He was very much frightened, never having been on a train before. We offered him some chocolates. He thought we were trying to poison him and he would not take them.

Two miles out of Waterford, the train pulled up short. Terence looked out of the window.

“The ‘Irregulars’ are holding up the train,” he told us. The old man, more frightened than ever, tried to crawl under a seat. But he was too fat to get all the way under, so he asked us to place our feet on top of him, the way we would hide him. After a while, I went to the window and looked out. Something scratched my chin. A bayonet, it was, in the hands of an “Irregular.”

“Take your face in out of that,” he ordered. I obeyed. From the luggage van, they took foodstuffs and then they ordered us along.

We travelled to a junction where we were to change trains. As the train pulled into the platform, we noticed the platform crowded with “Irregulars.” They tossed our baggage out of the van, ordered us clear of the train and sprinkled the carriages with petrol. A match was lit. You never saw such a blaze!

By motor car, we finished our journey to Mount Saint Benedict where the Dean’s sympathies were all with the “Irregulars.” Because of this, the “Black and Tans” many times raided us, in search of ammunition and men on the run from them. Up the drive they would come in their big lorries and we feeling like killing them, every man jack of them. After they searched everybody and every place, they would go into the refectory and order a meal. They had very bad table manners. We saw them tossing joints of meat across the room to one another on their bayonets. Of course, they never left without prisoners. Once, they took Harry Doyle, the cobbler who cared for our shoes. We wondered what we would do when our shoes were worn out. Happy was the thought we might have to go barefooted. To go barefooted, to us, was a great thing.

Oh, I remember one night at ‘‘prep,” that is, in the preparation room preparing our lessons for next day, when Bobby Coughlin held up his hand.

“What ails you?” asked Kane Smith, the teacher in charge.

“Please, sir, I just saw a hand at the window,” Bobby Coughlin said. You could have heard a dove’s breast feather floating to earth so great for a minute was the silence. A hand at the window! Was it a ghost? Or was it a “Black and Tan”? One was bad, the other was worse. Kane Smith turned very pale, he being of the “Irregulars” and wanted by the “Black and Tans.”

“Who else laid eyes on it?” said he excitedly.

“Please, sir, I did,” Paudeen Rogers, Bobby Coughlin’s deskmate admitted.

“What window was it at, Coughlin?”

“The window nearest to you, sir.”

“What window did you see it at, Rogers?”

“The same, sir.’’

Then Kane Smith strode the length of the room to their desk. Suddenly he caught them and dragged them to the open floor and knocked their heads together good and hard. Neither Coughlin nor Rogers could see the window nearest him from where they sat. The whole thing was a cod.

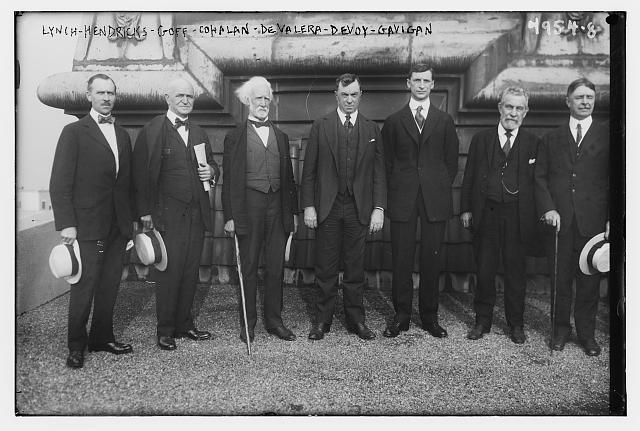

Came the good news. The fight was won. Ireland was a free state. That day there was no school at all all day. We went out on the hills and lit bonfires. The Dean ordered currant bread,—a great delicacy,—for tea. We cheered and we cheered and we cheered. We cheered and we hoarse from cheering. We cheered for Michael Collins the man De Valera appointed to beard the Welsh wizard, Lloyd George, in his den. We cheered for De Valera and we did not forget a cheer for poor Terence MacSweeney, Lord Mayor of Cork, who died for the cause, following a seventy odd days’ hunger strike.

But the news which at first we thought good news, and we not knowing the terms of the agreement, really was bad news. A free state! Sure, the whole thing was a farce: the country divided against itself, six counties staying lock, stock and barrel with England and the rest tied to England as firmly as it ever was except in name.

“The whole thing was De Valera’s fault,” we said. “Why did not De Valera go to Lloyd George himself? Why send an inexperienced man like Michael Collins ? Great fighter and all though he was, he was no diplomat.” De Valera, “took it easy,” we said, “while the Welsh wizard walked rings ’round poor Michael Collins.”

Poor Michael Collins, indeed! He was shot shortly and before we knew it Civil War was with us.

The parties who fought the civil war were the “Free Staters” who were satisfied with what they got and the “Republicans” who wanted a republic or else nothing.

This time the Dean’s sympathies were with the “Republicans” so of course, the “Free Staters” paid us a visit, and we grinding our teeth at them for traitors. Out of our warm beds, they roused us in the early morning. They searched our lockers, throwing our clothes on the floor, they searched under our mattresses, finding nothing but forbidden detective stories, and they even searched the water jugs. For what they searched, I don’t know. If it was ammunition, wasn’t it all well buried in the woods! Outside they had a Lewis gun trained on the house. Miss Keogh, the head matron, lost her temper about it. She went out to the captain and said: “Take that stupid toy away,” meaning the gun.

“Faith, we will, Mam, and you along with it,” said the captain.

When they left, sure enough they took Miss Keogh. They took her and put her in Kilmainham jail in Dublin. For a few days Miss Keogh sat patient and ladylike, thinking she soon would be released because nothing was known against her. When at the end of a few days they did not release her, and refused to say when they would, why, Miss Keogh just waylaid the jailer, tapped him on the head with his keys, took his clothes and walked out onto the street. Next morning she breakfasted at Mount Saint Benedict after riding half the night on a borrowed green bicycle to get there.

About that time a newspaper was started in Mount Saint Benedict. “The Daily Stinker,” it was called. It was written in ink, illustrated and distributed on the “Q.T.” The first issue contained war news and a full page caricature of the Dean fighting the entire Free State Army with one arm tied behind his back. The issue was captured by a vigilant teacher. In it he read the names of the editors and he sent them and “The Daily Stinker” to the Dean.

“This paper must be suppressed,” the Dean said.

“All right, Father. Thank you. Father,” Terence Smith and I said.

One day had “The Daily Stinker” been out of business, when Gorey, the town three miles distant from our school, was besieged. We were in Latin class when we heard the machine guns begin sending their messages of death. One of us was declining mensa. “Mensa,—rat-tat. Mensa, rat-tat. Mensam, ratta-tatta-tat. Mensae, rat-tat. Mensae, rat-tat. Mensa, rata-tatta-tatta-tat....”

“That will do,” the teacher said.

For the remainder of the day we listened to the firing, wondering what was happening, wondering to whom the battle would go. At bed time the report came: “Gorey has been taken by the Republicans.” How we cheered!

And still the fighting went on. Great men died on both sides. Father fought against son, brother against brother, cousin against cousin, friend against one time friend. At last in an attempt to stop the flow of blood, the Catholic Church intervened. The Republicans were excommunicated and preached against. It was the beginning of the end. The Free State was with bad grace accepted. The Republicans were crushed for the time being. Cosgrove was elected president. Quiet gradually fell on the land. Mount Saint Benedict was condemned by the new government as a bed of political unrest. It closed its doors. We went home.

Buck, Alan Michael. When I Was a Boy in Ireland. Lee and Shepard Co., 1936.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.