Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Jiu-jitsu Combat Tricks by H. Irving Hancock, 1904.

Two simple English words define a rule without the observance of which no one can expect to become anything like expert in jiu-jitsu. These two words are: Constant practice!

In taking up the ancient Japanese art of attack and defence, many Anglo-Saxons will be all enthusiasm at the outset, but will become gradually impatient under the monotony of practising the feats so constantly that expertness comes as a matter of course.

There are those who will read these chapters, and acquire a smattering knowledge of how many of the feats are executed. Here, or close to this point, the study of some readers will stop. The little knowledge that has been absorbed will be laid by in a corner of the mind, to be called into active use only if the moment of need arrives. And then, in a possible crisis, the knowledge that has been so slightingly obtained will prove useless. Readers who study jiti-jitsu in this fashion will never become jiu-jitsians.

"I know how that is done," reflects some reader, after he has gone over the description and has scanned an illustration; he practises the thing a few times with a friend—and then the feat is learned and the knowledge is ready for use!

Any reader who is satisfied to acquire his knowledge of the Japanese art so easily would do better to save his time at the outset by devoting it to some study to which he will be more faithful.

The few descriptions given in the last chapter would seem to indicate very easy mastery of that part of the subject. All that was written can be read thoughtfully in a half an hour; in another half-hour each of the feats can be practised several times with a complaisant friend—and the thing seems simple and easy enough! Many readers will be surprised when they are told that even the few feats explained in the last chapter should be practised assiduously for several weeks.

Yet this is the only possible way in which to acquire the tricks so that at last they can be employed instantly and with all desired effectiveness. The student should begin by performing any one feat very slowly, and, while increase of speed is absolutely necessary, this increase should be very gradual, effort being concentrated on the knack of striking or fending always with precision, to which even speed should be secondary for a long time—or until precision has become so much a matter of habit that speed will develop easily from it.

Practise at all odd times. When there are not more than two or three minutes of leisure, even, practise one of the feats and get a notch further ahead in its performance. Never get out of practise. Jiu-jitsu is not of so much use to the “rusty” adept. A Japanese teacher, when he has no pupil on hand to instruct, will practise with any friend who may drop into the gymnasium. If there be no one present but himself, the teacher will take up something that he can do by himself.

One day, some years ago, the author stood chatting with a Japanese teacher of the art. Without warning the little brown man suddenly fell forward, his body as straight and rigid as a log. He fell squarely on his face, not putting out either hand to save himself. In a twinkling he was on his feet again.

"That is a good thing to be able to do," explained the teacher. "I was alone this morning, so I practised it by myself. And here is something else that it is worth while to know how to do."

With the same suddenness he fell over backward, his body as rigidly straight as before. And it seemed as if he had no more than touched the floor when he was on his feet once more.

All of the edge-of-the-hand blows seem so simple as to require but little practice. The reader who so concludes will make a huge mistake. These blows are so useful in a variety of cases that they should be practised with assiduity. It must be borne in mind that the boxer can strike rapidly. The jiu-jitsian must be able to use the edge of his hand with even greater speed.

The boxer must always bend—"flex"—and then extend his arm before he can deliver a telling blow. The jiu-jitsian will find that at times he has the great advantage of being able to use the edge-of-the-hand blow without bend- ing his arm at all, and thus saving precious time in an encounter. If the hand, for instance, is hanging a little in front of the body, it can be made, by a single movement, to fly up and register a forcible blow against the adversary's jugular. A little experimenting will show the student a number of positions in which other edge-of-the-hand blows can be struck with a single movement of the arm—one upward, downward, or sideways. Never flex the arm when time can be saved by striking out without bending the arm.

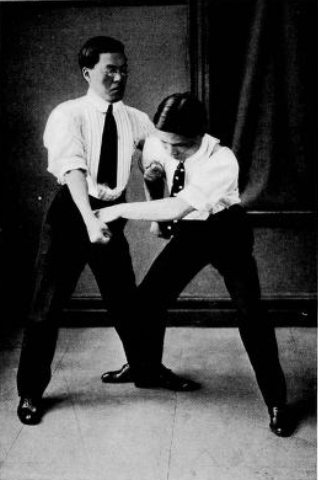

The arm-hook is by no means unfamiliar to boxers, by whom it is regarded as a foul that is never to be employed except in rough-and-tumble. But photograph No. 14 shows how it is employed in jiu-jitsu. Here the man on the defensive has swung his right arm over the boxer's left in such fashion that a "hook" is made at the elbows. In the same moment the man on the defensive has swung his body around to the side in order to make the hook more effective, and he holds his left hand in readiness to strike an edge blow against the boxer's right wrist. As soon as the boxer's right comes the man on the defensive is ready to meet and stop it.

But the man on the defensive has also put himself in a first-rate position for assuming the offensive and putting an end to the fight. A single movement of the arm will enable him to dart his left hand upward from the boxer's right wrist and to deliver a finger-tip jab in the solar plexus or in the abdomen. The student will do well to note in how many other cases he is thus able to turn at once from the defensive to the aggressive and put an end to further attack by his opponent.

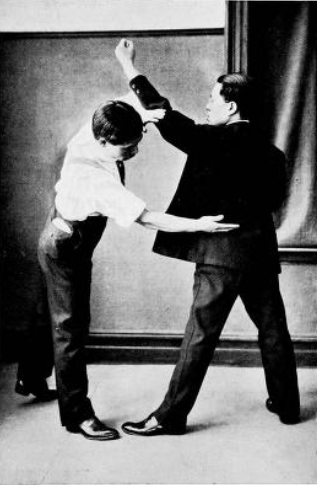

Photograph No. 15 depicts another style of defence against the boxer. Here the jiu-jitsian has struck up the boxer's left with the edge of his own left hand, at the same instant ducking, running in under the arm, and employing his right hand in a vigorous edge-of-the-hand blow over the boxer's left kidney. This blow, when well delivered, separates the boxer from any desire to continue hostilities.

It is to be noted here that the jiu-jitsian must accomplish the kidney blow with great speed and enough force. Otherwise the boxer will have an opportunity of registering a duplicate blow on the left kidney of his opponent. It will be seen how easy it would be for the boxer, if quick enough, and if dealing with a slow adversary, to swing around and inflict his own kidney blow.

When one is ducking under the boxer's arm and striking the kidney blow it will easily occur how simple it would be to strike, instead, at the base of the spine. But this latter is a blow that should never be employed with the edge of the hand. It is decidedly too dangerous. The base-of-the-spine blow, delivered at a certain angle, and at a certain point of impact, would probably result in leaving the combatant so struck bed-ridden for life. In general it must be insisted that there is altogether too much danger in attacking the lower end of the spine with such a blow.

A considerable variety of blows in the abdomen, at the sides, and over the kidneys can be studied out by the industrious. A general hint will be enough. Any position that leaves a combatant's hand or elbow between the opponent's arm and body gives a valuable opportunity. The fingers, the edge of the hand, or the point of the elbow may be used for swift attack against the soft parts. The elbow, when in position, may be used effectively for a blow in the adversary's short ribs.

Nor must the use of the knee be forgotten when at close quarters. A jab with the point of the knee may be employed against the abdomen or side when both hands are busy. If one is behind his adversary he is often able to “butt” the point of one of his knees in over the kidney. A kidney blow delivered with any force at all is one that discourages further fighting.

If one of the contestants is quick enough to see and stop a rising knee from striking him, a blow with the edge of the hand just above the knee will be found very useful in forcing that leg to straighten out again.

It is time, now, for the student who has gone faithfully thus far to begin to study out problems for himself. He should, in any given position of encounter, learn by experiment how many of the holds and blows he has so far learned may be applied with effect, and which feats give better results than others.

It frequently happens that two antagonists are practically locked—that is, assailant and victim each has both arms employed, and for either to let go would seem to expose him to defeat. In this position figure out all possible ways of letting one hand go in order to make an attack to advantage. Or, if it is necessary that both hands remain engaged where they are, see whether a jab can be given with either elbow. Sometimes it will be found that the point of the knee is the only weapon that can be employed with safety against a vigilant opponent. Whatever the strong factor is in the situation, find it and employ it at once—before the other man can find some disconcerting possibility.

Hancock, H. Irving. Jiu-jitsu Combat Tricks: Japanese Feats of Attack and Defence in Personal Encounter, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.