Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

“Leaves in the Storm” from A Tuscan Childhood by Lisi Cecilia Cipriani, 1907.

Victor Hugo, in writing of himself as a child, says:

When the north-wind strikes the throbbing waves

The convulsive ocean tosses at one time

The three-decked ship thundering with the storm

And the leaf escaped from the tree on the shore.

We, too, were leaves in the great storm, the storm of the religious and political up-heaval in Italy, for our life began but a short while after Italy had been made one, while the country was still suffering in the efforts to adjust the old with the new.

The religious phase of our life was most affected by this unsettled condition of our environment. It is here that the direct influence of historical events shows most clearly. A brief account of our family history is necessary for a full understanding of the situation and certain incidents that I am going to relate. This history is not without poetical interest. I may add. however, that whatever is known to me on the subject I have found out for myself. The reserve about anything that would have led us to be proud of our race and our position was almost ostentatious.

The famous chronicles of Malaspini mentions the Cipriani among the sixteen families who founded Florence. Five of these families, including our own. were all agnates, and descended from Galigaio, a Roman patrician, who the chronicles tell us, was a companion-in-arms of Julius Cesar, and assisted him in the Siege of Fiesole.

The names of these five branches lend some probability to this Roman origin, though we, of course, know that during the Middle Ages the nobility of central Italy took pride in descending from the Romans, whereas the nobles of northern Italy preferred to trace their descent back to the twelve peers of Charlemagne. We found out this presumed Roman origin by ourselves, and the fact that it was almost forbidden knowledge made us particularly delight in our discovery.

Malaspini mentions our family sometimes as Cipriani, and sometimes as Delia Pressa, a name which, by the way, is also given us in the modern Annuary. The Cipriani were staunch Ghibellines and good fighters. Dante, under the name of Delia Pressa, in the Sixteenth Canto of the Paradiso, mentions us where he says: "The Delia Pressa already knew how it behooves to rule and in Galigaio's house the hilt and the pommel were already gilt." This passage, because it was in Dante, we, of course, knew.

When the Ghibellines were defeated by the Guelphs, the Cipriani were among those who preferred exile to humiliation. They would neither renounce their prerogatives and enroll in a Guild, nor change their name.

Thirteen Cipriani, history tells us, were captured by the Guelphs and condemned to death. Twelve of these escaped, and only one, Capaccio, remained in their hands. Perhaps the name (Capaccio means bad head) was fatal. He was beheaded on the Canto di Capaccio, that to this day bears his name, and is opposite the beautiful balcony of Palazzo dell Arte della Seta, designed by Vasari.

Then my grim Ghibelline fathers went into exile. One branch settled in France, but died out. The other settled on the Northern promontory of Corsica, Capo Corso, where our branch of the family remained till the beginning of the nineteenth century, when my grandfather, Matteo Cipriani, came back to Italy. It was he who bought the villa at Leghorn, where we spent the happiest days of our childhood.

To this Corsican influence I trace certain pronounced family characteristics, principally tenacity and endurance. The environment under which our race developed during these centuries was, I think, a distinctly desirable one. We never be-came court nobility, and we were thus saved from the excesses to which the European nobles gave themselves up from the Renaissance to the French Revolution. Moreover, it endowed us with exceptionally good physical constitutions, for the development of the body was in every way favored by the rough out-of-door Corsican life.

The life we led during all these years in Corsica was no doubt primitive compared to the luxury that reigned at the French and Italian courts, and we remained very-near the Middle Ages. I can almost say that in our family we skipped the Renaissance.

When my grandfather returned to Italy the family, in spite of its long absence from Florence, resumed its place at once among the Florentine patricians. Moreover, the marriages contracted by my aunts, and the daughters of another Cipriani, who had returned to Italy at the same time my grandfather did, connected us by close family ties with Italians of our own rank. I do not think that my father ever realized that his family had just returned to Italy after an absence not of years, but of centuries. We children, of course, never felt this at all, though we were very proud of our Corsican connections.

My Ghibelline fathers went into voluntary exile. When they came back the struggle of the country against the church and the rulers the Roman Church supported, had not ended. It is true that the Guelph and Ghibelline parties had long disappeared. It is true that no German emperor was upheld against the head of the church. But the ideal of Dante, of an Italian strong and free, untrammeled by the selfish bonds of the church and petty rulers, had lived on.

It seems only poetic justice that when, after their long exile, these Ghibellines returned to the cradle of their race, they should successfully finish the task their fathers had begun. My uncles and my father all fought bravely and unselfishly for the freedom of Italy, and their party finally conquered. Italy became one. And the man who, as governor, first ruled the provinces wrenched from the Pope, the very provinces that a thousand years ago Pepin had granted, thus establishing the temporal power of the church—the man was my uncle.

Am I not justified in seeing a grim poetry in this? The Guelphs conquered us; they pulled down our palaces, and leveled them to the ground, strewing salt over them; they drove us into exile, so that even women and children faced every hardship; and at last, after hundreds of years had passed, we came back and in turn conquered our conquerors.

In 1859 my uncle was Governor of the Romagne. It was then, I think, that he and my father seceded from the Roman Catholic Church. In my father's case this was much more marked, because he married a Protestant, and decided to have his children brought up in their mother's faith, though curiously enough we were all christened in the Catholic Church. Personally I have always regretted this secession, for I think that we would have been much happier if we had grown up in the same religion as our friends and relatives.

The religious question was, therefore, a burning one in my childhood. Relatives, friends, servants, all were Catholics. My mother was a Protestant, it is true, but with her exception we met few Protestants, except the governesses and the tutors, and I confess that I antagonistically associated Protestantism with them.

Our religious training was a curious one. They did not try to teach us what to believe, but rather instructed us carefully as to what we ought not to believe. We were told not to believe in saints, miracles, and relics. We were told that Catholicism stands for ignorance. This last statement, however, soon aroused grave doubts in my mind, since many of the persons I esteemed and admired most were Catholics. We were told that it was absurd for a priest to give absolution; that confession was an evil thing. And we listened in silence.

I was the skeptic of the family. After having been told how many things I was not to believe, I learned to be ready to disbelieve any one and anything, even what my mother told me; not that I thought she lied, but I simply took it for granted that she considered it best to tell us just that, and I did not dispute her right to do so.

I remember distinctly that one morning, when I was barely five years old, my mother sent for Ritchie and me. After having had our faces well scrubbed and clean pinafores put on, we were taken to her morning-room. Then she formally began our religious instruction. Up to this time I had only been made to learn the Lord's Prayer in English; and I rattled it off with very little concern as to what it meant. This morning my mother told us that there was a God. She also told us that this God was perfect, all-powerful, and everywhere at once. This last seemed incredible to me, and so she explained that he was everywhere, and could see everything. No matter where a thing happened he knew about it. This information she considered enough for the first lesson, and we were sent back to the nursery.

It happened that this very day I saw Ritchie throw a little embroidered waist on the top of the mosquito-netting that hung around our little beds, and when the nurses were looking for the jacket and Ritchie vouchsafed no information, having perhaps forgotten what he had done, I thought the time had come for a conclusive experiment. I thought I had my chance to prove whether this Protestant God they told me about was any better than the scorned saints painted on the walls.

I spoke no word while the nurses were hunting. I did not cry out, as I should have at any other time, "Ritchie hid it." No, indeed; I waited for the good Lord to tell. At night on drawing out the mosquito-netting the little jacket was found. Then I informed the nurses I knew it was there. This led to the belief that I had hidden it there myself. I occasionally did hide things, and their suspicion was not altogether unjustified. But this time I declared that I had not put it there; Ritchie had done so, and it was unfair to punish me. They took me to my mother to be punished, for she inflicted all punishments herself, and there I burst into tears, and tried in vain to explain that I thought God, who saw everything, and could do anything he wanted, should have told the nurses himself.

My mother and the nurses did not understand the situation at all. I was severely punished, and left to my thoughts. As I have mentioned already, it was my habit to boil inside, so after having wiped my eyes, I took my punishment bravely, but I remained a skeptic in the bottom of my heart.

This skepticism was all the more profound as I never expressed it, and it remained unsuspected and uncorrected. In a thoroughly skeptical spirit did I begin the regular study of Bible history when I was not yet eight years old. But there were complications.

I had a governess then, the only one among many of whom I have an absolutely pleasant recollection, Fraeulein Anna, a charming girl of about twenty, who must have been an exceptionally good teacher. But—fate willed it—she was the daughter of a well-known German socialist, who was an atheist. Though I heard the details about her life and her family only much later, when I was almost grown up, yet even at the time I knew that her father was something terrible, a socialist who did not believe in God, and that she had been baptized with champagne. This did not shock me. Indeed, I connected it in my mind with the launching of a ship, a frequent festive event in the ship-yards at Leghorn, and I liked her all the better for not having been baptized with plain water like other common mortals.

Again you might say, "How could your mother, if she wished you to have any religion at all, trust you to the daughter of an atheist?" And I can answer, to begin with my mother's religion was a passive one. She did not want us to be Catholics, but her real interest in religious questions seemed to end there. Besides, Fraeulein Anna did not profess atheism herself, and she had been put in our house by the German Protestant clergyman at Leghorn. He was a fine old man and my mother had great confidence in him.

Fraeulein Anna was perhaps the only governess who did not attack Catholicism, but she did not go beyond this. She carefully made me learn the Bible history. She made sure that I knew the names of the patriarchs and their sons, and that I did not confuse the deluge with the Tower of Babel. She was, in fact, the first one who taught me how to study, something for which I am grateful to this day. If I asked any questions, she answered the practical ones, and dismissed any that would have led to a theological discussion. With prompt kindness she would get a map, and, at my desire, show me the exact position of the Red Sea, but she had nothing to say when I wanted to know why Eve should be punished for eating the apple before she had been taught to distinguish between right and wrong—a simple question, one which has puzzled many besides myself.

Some points troubled me much. How could God make the world out of nothing? If he had even had a little grain of dust, he might have made it grow, but to make something out of nothing, and be everywhere at the same time; these were things I could not understand. With Eve I deeply sympathized. I reasoned that it was not fair play. If she knew what was right and what was wrong, she might be punished, but before she really knew that a thing was wrong, she did not deserve to be punished. This, of course, was in accordance with our own nursery rules, for if we did anything we had been forbidden to do, the punishment was severe, but a first offense, when we could honestly say we did not know it was wrong, was always at least half- forgiven.

If I dwell upon these details, it is not because I consider myself particularly interesting as an individual, but because I am convinced that my experience is that of many children who grow up in a religion different from that of the people around them, especially if, for any reason, their religious interest is keen. Mine was great, and continued intense for many years. I do not think that my brothers and sisters troubled about religious questions the way I did. They all, I think, found it easier to obey in the spirit and in the word. They were told that it was best for them not to be Catholics, and to be Protestants, and that sufficed.

Three years passed after Fraeulein Anna first taught me Bible history. The governess whom I have already mentioned with particular dislike was with us then. As I have explained, she was always arbitrary and often unreasonable. Moreover, she lacked even elementary tact. I did not respect her. Her attitude toward religious questions was such that in telling about them now I must expect to be accused of exaggeration.

She encouraged my brother Alick to make fun of the priests. This was and is only too common in Italy among a certain set of people, and particularly among the men of the lower classes. To Fraeulein it may have seemed funny and new, but I thought then, and I think now, that it was absolutely inexcusable.

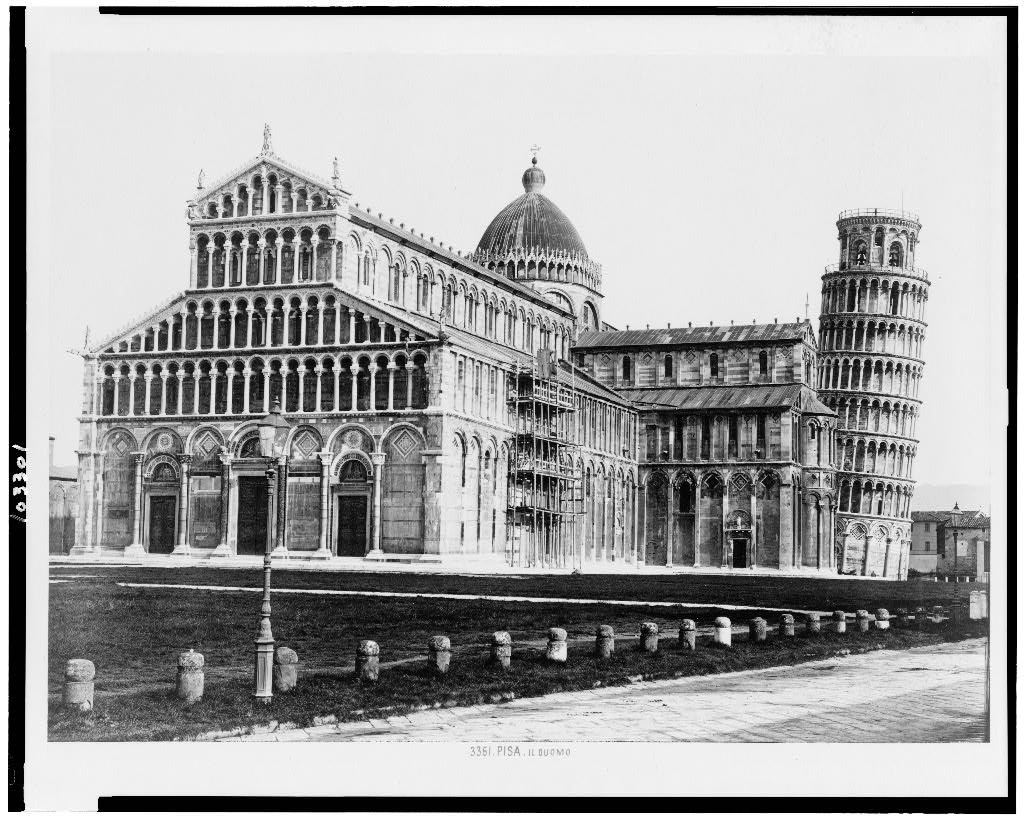

She used to like to go to the Duomo at Pisa to listen to the beautiful music at vesper services. We children were not particularly musical, and in order to keep us from being bored, she had taught us to nickname the canons as they sat in their seats in the altar circle. This, it seems to me, was all the worse, because we as Protestants should have been taught to respect the ministers of another religion. And, besides, merely the respect due old age made it wrong for us to nickname them according to their resemblance to a horse, or a dog, or a rabbit, or a fox, etc.

So well trained were we not to complain of our governesses, that my mother did not know of this till years later.

It was with this governess, Fraeulein Helene, that the climax for me came, and that I cast off both Catholicism and Protestantism, turning to the older faith that the Christians had crushed. One day I found an old piece of newspaper that contained the following item:—"Last night, under the influence of Bacchus, some soldiers changed a temple of Venus into a temple of Mars. The police promptly interfered."

When a young reporter expressed in this flowery way the drunken brawl of some soldiers, he surely had no conception of how it would for years affect the inner life of a little Florentine patrician.

Greek mythology was perfectly familiar to us. In fact, playing the gods was one of our common games. We all had been given a name of some Greek god or goddess. An older boy, who occasionally used to play with us, was Jove; my sister Totty was Minerva; Ritchie was Mercury, because he was constantly sent on errands; and I, to my bitter sorrow, was Proserpina. I protested with tears against this, because they had called a boy whom I detested Pluto, and even in a game I did not want to be considered his wife. But, as I have already remarked, childhood is cruel. "The children," being the oldest, had taken upon themselves the right of distributing the parts, and did not care whether they spoiled my pleasure or not. When I appealed to my mother, her decision was: "Why, your not liking your husband makes your part all the more natural." And so I had to keep my name.

Of course, we had been told that the Greek gods were no longer worshiped; yet the statement in print was absolute. I knew the words by heart—"Under the influence of Bacchus, some soldiers changed a temple of Venus into a temple of Mars." The police had interfered because—because, no doubt, the police did not wish the soldiers to worship the Greek gods any more than our governesses wished us to pray to the saints. The thing was perfectly clear to me. I realized that once again knowledge had been withheld from us. The Greek gods still had their worshipers.

As I thought the matter over my eagerness to have the worship of the Greek gods openly established and not interfered with by the police grew greater and greater.

I have forgotten to mention, in telling the family history, that Malaspini states that one of my ancestors married a grand-daughter of Octavian, the Emperor. Now follows my childish reasoning. If we descended from Octavian, the Emperor, through him we went back to Julius Caesar; from Julius Caesar we went back to Æneas; from Æneas evidently we went back to Venus; from Venus we went back to Saturn! When the Greek gods loom large again we, who actually had descended from them, would come into our own; and they that ruled us had kept us ignorant of this, just as they had kept us ignorant of other things concerning our family that we might justly be proud of.

I longed for the time when I should be grown up, and could bring about the open worship of the Olympians.

For a long time my interest in this was keen, but as I never spoke about it to any one, finally I almost forgot the whole story. It only came back to me when many, many years after I came across the same trite expression in referring to some drunken soldiers' brawl.

But I have not waited for the gods in vain. They have come to me in all their classical splendor, though not as I had looked forward to them as a child. In art and literature I have finally come to my own. They have opened a glorious new world to me, where I can find refuge whenever the modern, Protestant world seems too cold, too barren, too hard.

Cipriani, Lisi Cecilia. A Tuscan Childhood, The Century Co., 1907.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.