Interview with Buddy Jones, November 2020

Written by Andre James

Buddy Jones: My problem with teachers started at Irving Elementary and followed me to University Heights Junior High School in Riverside, California. How little they understood about how I learn. However, many years later I have decided to cut them some slack. After all, so little was known about dyslexia in the early 50’s.

I was held back in first grade. I have no idea what I missed in that first year that they insisted I repeat. At six, starting over had little social impact. And one additional benefit. My younger sister Wanda joined my class. Although 15 months younger, she protected me from an onslaught of peer ridicule.

In the 50’s, Riverside Unified Schools included 3rd and 4th in one classroom. Once again, my teacher was concerned about my reading and writing progress. Socially, I was doing fine. My athletic abilities translated to great popularity anytime a pickup baseball, football or basketball game was at hand. But during this time, my teacher was sharing her concerns with my mother. Although quite athletic, I still had problems like tying my shoes and deciphering sentences. No one knew I was trying to read from right to left. A true mystery to my teachers, my family and to me.

New labels were whispered between teachers. Slow learner. Dumb. Monikers that can brand a kid for a lifetime. My anger grew when my peers started using these labels. You see, I was more than capable of reading and matching words with things. It was just in those damn sentences where letters moved around like the ball in a pinball machine. Working against this deficiency, I turned to rely more on my social skills.

Was I capable of learning? I apprenticed at Buster’s Auto Repair Shop after school, on weekends and during the summer. Buster, my dad was and would be considered today, a master mechanic, master toolmaker and a master teacher. He had a way to keep me interested in learning about the physics of how things worked, how to identify and fix a problem. Unlike the one-way unified school district, Buster would say, “When it comes to learning, its different strokes for different folks.”

I know many guys idolize their dads.

But, let me share a simple example that might get you on board:

Changing The Brakes.

First Buster would layout the tools. Then he would say, “I want you to watch everything I do.”

I watched. Next, he would hand me the tools and say,

“OK, now you change the brakes.” Wow, was I an instant mechanic? With trepidations, I started on the next set of brakes. Inevitably, I got stuck.

“So, (not in a scolding or demeaning tone) you did not see everything I did?” Buster observes. “Watch again.”

I watched again. Then, I soloed on the third brake set.

“OK, now that you know how to change the brakes, tackle all four sets of brakes on that car.” In one afternoon, I was a certified brake-master. I had acquired an employable skill, useful at any local service station. A brake-master at ten years old!

Practical Solutions – Although not trained in the diagnostics of dyslexia, Mrs. Powell, my mother’s best friend and my Sunday School teacher, identified my challenges with the written word. Every week we were sent home with a religious concept written on a card that we would be expected to memorize for the next session. As you can imagine, I started out failing at this task. After one session she had me stay behind. She read the concept out loud. The next week, I could recite it, word for word. So, it became habit that I would arrive before class to listen to Mrs. Powell read out loud. And that is what I will label stumbling into phonics.

Bad Solutions - To solve the misunderstanding of my dyslexia, the teacher approached my parents with a recommendation of sending me to a school for retarded kids.

Buster was flustered. How could I risk having Buddy change the entire set of brakes on a customer’s car and yet believe who could not grasp his ABC’s? Not jumping to conclusions he approached the school principal Mr. White and gained permission to observe my class. After a few sessions, Buster asked to engage the class in a workshop in what I will describe as “applied math and physics”.

Let me take you through that lesson that has stayed with me for 70 years.

Pops rolls out a greasy shop rag on the table at the front of the class. Lined up are a variety of tools and parts. Wrenches, some of which Buster designed for Snap-on Tools. But, that is another story. Addressing the class, he engages us in a Socratic discussion:

Lesson One: Fractions for Identifying Tools

“What is the size of this wrench?” No one answers.

“You measure the size by the diameter of the opening. This is a one inch wrench.”

“So, what does that make this smaller wrench? Who knows their fractions?” Still no answer.

“That is a half-inch wrench”, I proudly exclaim.

“Yes, and as you can see, it is half the size opening as the one inch.”

One by one he holds up 1/4 , ¾, 7/8 inch wrenches, nuts and bolts. And once again I am the only one who can identify every item.

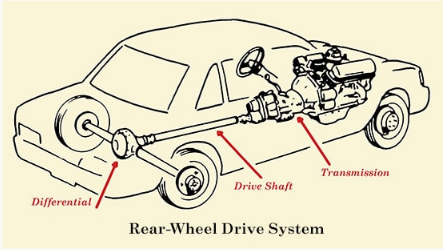

Lesson Two: The Physics of Mobility

Dad draws the outline of a car on the board. He sketches in several of the key components.

“Who can tell me what makes a car run?”

“The engine”, one student declares.

“And how does that engine get the car to move?”

There are lots of quizzical looks moving criss-cross around the room.

“Buddy, why don’t you come up and take a shot at explaining how a car moves.”

I went to the board to deliver my first lecture. I explained how the combustion of the engine moved the pistons that were connected to the crankshaft. Then I explained how the crankshaft was connected to the transmission gears to determine the speed and power of the driveshaft. I continued by pointing out how the differential gearbox translated the driveshaft’s rotation into a 90 degree spin of the rear axle that was connected to the tires. End of lesson for the fourth grade!

There was never another word spoken about sending me to any kind of special needs class. Somehow, I problem-solved my way through junior high and high school. Subsequently, I was given a scholarship to one college but ended up playing football for John Madden and Don Coryell at San Diego State. And after college I was given an opportunity to try out for the Jets and then the Chargers, two prominent National Football League teams. But, after a few hits from much bigger men than me, I was convinced I could find a more fruitful career handling the daily blocking and tackling of my reading and writing skills.

Following my brief athletic career, I turned to developing my leadership skills, learning more about the management of teams. After building a contracting business I ran for thirteen years, repairing roads and buildings in our National Parks, I retired. Now, I am most proud that in some small way, my sons have followed in my footsteps by striking out to independently pursue their interests. Interests that they have transformed into successful sole proprietorships.

Like grandfather, like father, like sons.

When I look back at a life filled with the riches of many remarkable, rewarding experiences, teaming up with my dad to teach my schoolmates how a car works, is among the tops on my list. Now that is a memory you can take to the bank!

However, with all due respect to Buster, we haven’t begun to describe the influence of Geraldine Labor Merriman Jones, my mother.

Buddy Jones

Interview with Andre James

November 2020

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.