Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Elements of Culture in Native California by Alfred Louis Kroeber, 1922.

Money

Two forms of money prevailed in California, the dentalium shell, imported from the far north; and the clam shell disk bead. Among the strictly northwestern tribes dentalia were alone standard. In a belt stretching across the remainder of the northern end of the state, and limited very nearly, to the south, by the line that marks the end of the range of overlay twined basketry, dentalia and disks were used side by side.

Beyond, to the southern end of the state, dentalia were so sporadic as to be no longer reckoned as money, and the clam money was the medium of valuation. It had two sources of supply. On Bodega bay, perhaps also at a few other points, the resident Coast Miwok and neighboring Pomo gathered the shell Saxidomus aratus or gracilis. From Morro bay near San Luis Obispo to San Diego there occurs another large clam, Tivela or Pachydesma crassatellaides.

Both of these were broken, the pieces roughly shaped, bored, strung, and then rounded and polished on a sandstone slab. The disks were from a third of an inch to an inch in diameter, and from a quarter to a third of an inch thick, and varied in value according to size, thickness, polish, and age. The Pomo supplied the north; southern and central California used Pachydesma beads. The Southern Maidu are said to have had the latter, which fact, on account of their remoteness from the supply, may account for the higher value of the currency among them than with the Yokuts. But the Pomo Saxidomus bead is likely also to have reached the Maidu.

From the Yokuts and Salinans south, money was measured on the circumference of the hand. The exact distance traversed by the string varied somewhat according to tribe; the value in our terms appears to have fluctuated locally to a greater degree. The Pomo, Wintun, and Maidu seem not to have known the hand scale. They measured their strings in the rough by stretching them out, and appear to have counted the beads when they wished accuracy.

Associated with the two clam moneys were two kinds of valuables, both in cylindrical form. The northern was of magnesite, obtained in or near southeastern Pomo territory. This was polished and on baking took on a tawny or reddish hue, often variegated. These stone cylinders traveled as far as the Yuki and the Miwok.

From the south came similar but longer and slenderer pieces of shell, white to violet in color, made sometimes of the columella of univalves, sometimes out of the hinge of a large rock oyster or rock clam, probably Hinnites giganteus. The bivalve cylinders took the finer grain and seem to have been preferred. Among the Chumash, such pieces must have been fairly common, to judge from finds in graves. To the inland Yokuts and Miwok they were excessively valuable.

Both the magnesite and the shell cylinders were perforated longitudinally, and often constituted the center piece of a fine string of beads; but, however displayed, they were too precious to be properly classifiable as ornaments. At the same time their individual variability in size and quality, and consequently in value, was too great to allow them to be reckoned as ordinary money. They may be ranked on the whole with the obsidian blades of northwestern California, as an equivalent of precious stones among ourselves.

The small univalve Olivella biplicata and probably other species of the same genus were used nearly everywhere in the state. In the north, they were strung whole; in central and southern California, frequently broken up and rolled into thin, slightly concave disks, as by the Southwestern Indians of today. Neither form had much value. The olivella disks are far more common in graves than clam disks, as if a change of custom had taken place from the prehistoric to the historic period. But a more likely explanation is that the olivellas accompanied the corpse precisely because they were less valuable, the clam currency either being saved for inheritance, or, if offered, destroyed by fire in the great mourning anniversary.

Haliotis was much used in necklaces, ear ornaments, and the like, and among tribes remote from the sea commanded a considerable price; but it was nowhere standardized into currency.

Tobacco

Tobacco, of two or more species of Nicotiana, was smoked everywhere, but by the Yokuts, Tübatulabal, Kitanemuk, and Costanoans it was also mixed with shell lime and eaten.

The plant was grown by the northwestern groups such as the Yurok and Hupa, and apparently by the Wintun and Maidu. This limited agriculture, restricted to the people of a rather small area remote from tribes with farming customs, is curious. The Hupa and Yurok are afraid of wild tobacco as liable to have sprung from a grave; but it is as likely that the cultivation produced this unreasonable fear by rendering the use of the natural product unnecessary, as that the superstition was the impetus to the cultivation.

Tobacco was offered religiously by the Yurok, the Hupa, the Yahi, the Yokuts, and presumably by most or all other tribes; but exact data are lacking.

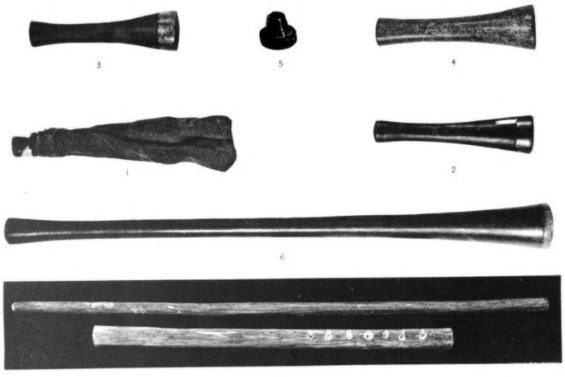

The pipe is found everywhere, and with insignificant exceptions is tubular. In the northwest, it averages about six inches long, and is of hardwood scraped somewhat concave in profile, the bowl lined with inset soapstone.

In the region about the Pomo, the pipe is longer, the bowl end abruptly thickened to two or three inches, the stem slender. This bulb-ended pipe and the bulb-ended pestle have nearly the same distribution and may have influenced one another. In the Sierra Nevada, the pipe runs to only three or four inches, and tapers somewhat to the mouth end.

The Chumash pipe has been preserved in its stone exemplars. These normally resemble the Sierra type, but are often longer, normally thicker, and more frequently contain a brief mouthpiece of bone. Ceremonial specimens are some times of obtuse angular shape.

The pottery making tribes of the south use clay pipes most commonly. These are short, with shouldered bowl end.

In all the region from the Yokuts south, in other words wherever the plant is available, a simple length of cane frequently replaces the worked pipe; and among all tribes shamans have all-stone pieces at times.

The Modoc pipe is essentially Eastern: a stone head set on a wooden stem. The head is variable, as if it were a new and not yet established form: a tube, an L, intermediate forms, or a disk.

The Californians were light smokers, rarely passionate. They consumed smaller quantities of tobacco than most Eastern tribes and did not dilute it with bark. Smoking was of little formal social consequence, and indulged in chiefly at bedtime in the sweat-house. The available species of Nicotiana were pungent and powerful in physiological effect, and quickly produced dizziness and sleep.

Various

The ax and the stone celt are foreign to aboriginal California. The substitute is the wedge or chisel of antler among the Chumash of whale’s bone driven by a stone. This maul is shaped only in extreme northern California.

The commonest string materials are the bark or outer fitters of dogbane or Indian hemp, Apocynum cannabinum; and milkweed, Asclepias. From these, fine cords and heavy ropes are spun by hand. Nettle string is reported from two groups as distant as the Modoc and the Luiseno. Other tribes are likely to have used it also as a subsidiary material.

In the northwest, from the Tolowa to the Coast Yuki, and inland at least to the Shasta, Indian hemp and milkweed are superseded by a small species of iris I. macrosiphon from each leaf of which two thin, tough, silky fibers are scraped out. The manufacture is tedious, but results in an unusually fine, hard, and even string. In the southern desert, yucca fibers yield a coarse stiff cordage, and the reed Phragmites is also said to be used. Barks of various kinds, mostly from unidentified species, are employed for wrappings and lashings by many tribes, and grapevine is a convenient tying material for large objects when special pliability is not required.

Practically all Californian cordage, of whatever weight, was two-ply before Caucasian contact became influential.

The carrying net is essentially southern so far as California is concerned, but connects geographically as well as in type with a net used by the Shoshonean women of the Great Basin. It was in use among all the southern Californians except those of the Colorado river and possibly the Chemehuevi, and extended north among the Yokuts. The shape of the utensil is that of a small hammock of large mesh. One end terminates in a heavy cord, the other in a loop.

A varying type occurs in an isolated region to the north among the Pomo and Yuki. Here the ends of the net are carried into a continuous headband. This arrangement does not permit of contraction or expansion to accommodate the load as in the south. The net has also been mentioned for the Costanoans, but its type there remains unknown. It is possible that these people served as transmitters of the idea from the south to the Pomo.

A curious device is reported from the Maidu. The pack strap, when not of skin, is braided or more probably woven. Through its larger central portion the warp threads run free without weft. This arrangement allows them to be spread out and to enfold a small or light load somewhat in the fashion of a net.

The carrying frame of the Southwest has no analogy in California except on the Colorado river. Here two looped sticks are crossed and their four lengths connected with light cordage. Except for the disparity between the frame and the shell of the covering, this type would pass as a basketry form, and at bottom it appears to be such. The ordinary openwork conical carrying basket of central and northern California is occasionally strengthened by the lashing in of four heavier rods. In the northeastern corner of the state, where exterior influences from eastern cultures are recognizable, the carrier is some times of hide fastened to a frame of four sticks.

The storage of acorns or corresponding food supplies is provided for in three ways in California. All the southern tribes construct a large receptacle of twigs irregularly interlaced like a bird’s nest. This is sometimes made with a bottom, sometimes set on a bed of twigs and covered in the same way. The more arid the climate, the less does construction matter. Mountain tribes make the receptacle with bottom and lid and small mouth. In the open desert the chief function of the granary is to hold the food together and it becomes little else than a short section of hollow cylinder. Nowhere is there any recognizable technique. The diameter is from two to six feet. The setting is always outdoors, sometimes on a platform, often on bare rocks, and occasionally on the ground. The Chumash did not use this type of receptacle.

In central California a cache or granary is used which can also not be described as a true basket. It differs from the southern form in usually being smaller in diameter but higher, in being constructed of finer and softer materials, and in depending more or less directly in its structure on a series of posts which at the same time elevate it from the ground. This is the granary of the tribes in the Sierra Nevada, used by the Wintun, Maidu, Miwok, and Yokuts, and in somewhat modified form a mat of sticks covered with thatch by the Western or mountain Mono. It has penetrated also to those of the Pomo of Lake county who are in direct communication with the Wintun.

In the remainder of California, both north and south, large baskets their type of course determined by the prevailing style of basketry are set indoors or perhaps occasionally in caves or rock recesses.

The flat spoon or paddle for stirring gruel is widely spread, but far from universal. It has been found among all the northwestern tribes, the Achomawi, Shasta, Pomo, Wappo, Northern Miwok, Washo, and Diegueno. The Yokuts and Southern Miwok, at times the Washo, use instead a looped stick, which is also convenient for handling hot cooking stones. The Colorado river tribes, who stew more civilized messes of corn, beans, or fish in pots, tie three rods together for a stirrer. The Maidu alone are said to have done without an implement.

Kroeber, A. L. Elements of Culture in Native California, University of California Press, 1922.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.