Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Elements of Culture in Native California by Alfred Louis Kroeber, 1922.

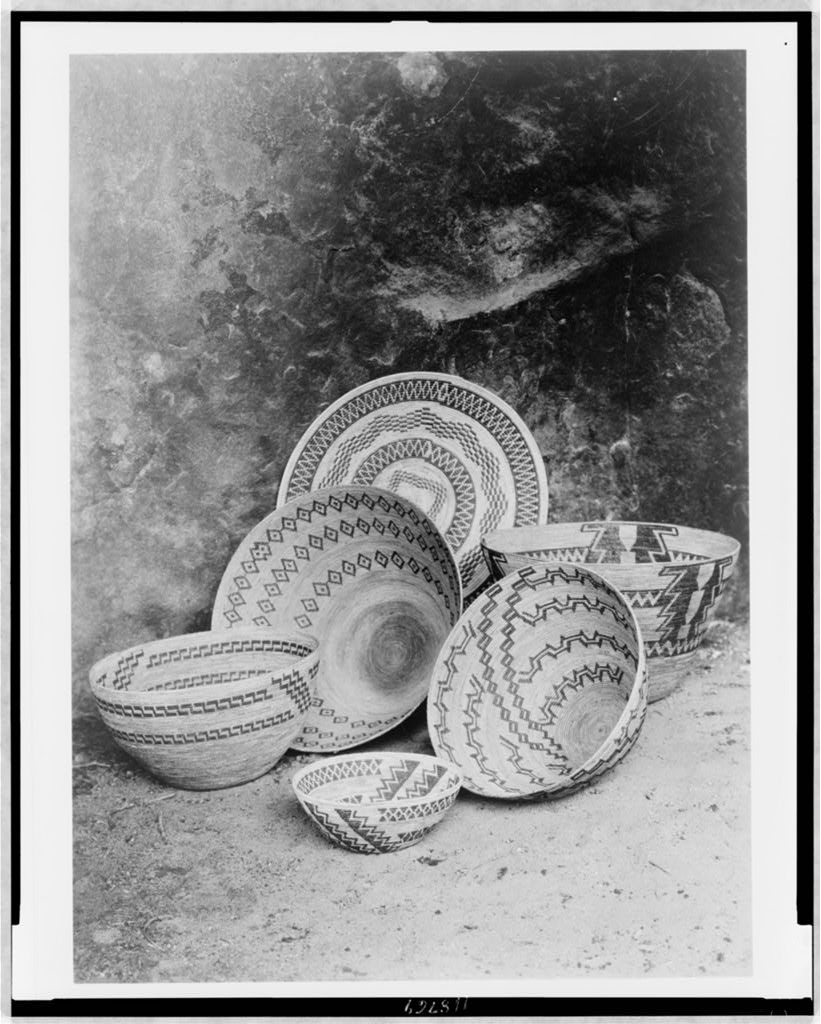

Textiles

Basketry is unquestionably the most developed art in California, so that it is of interest that the principle which chiefly emerges in connection with the art is that its growth has been in the form of what ethnologists are wont to name "complexes." That is to say, materials, processes, forms, and uses which abstractly considered bear no intrinsic relation to one another, or only a slight relation, are in fact bound up in a unit. A series of tribes employs the same forms, substances, and techniques; when a group is reached which abandons one of these factors, it abandons most or all of them, and follows a characteristically different art.

This is particularly clear of the basketry of northernmost California. At first sight this art seems to be distinguished chiefly by the outstanding fact that it knows no coiling processes. Its southern line of demarcation runs between the Sinkyone and Kato, the Wailaki and Yuki, through Wintun and Yana territory at points that have not been determined with certainty, and between the Achomawi (or more strictly the Atsugewi) and the Maidu. Northward it extends far into Oregon west of the Cascades. The Klamath and Modoc do not adhere to it, although their industry is a related one.

Further examination reveals a considerable number of other traits that are universally followed by the tribes in the region in question. Wicker and checker work, which have no connection with coiling, are also not made. Of the numerous varieties of twining, the plain weave is substantially the only one employed, with some use of subsidiary strengthening in narrow belts of three-strand twining. The diagonal twine is known, but practiced only sporadically. Decoration is wholly in overlay twining, each weft strand being faced with a colored one.

The materials of this basketry are hazel shoots for warp, conifer roots for weft, and Xerophyllum, Adiantum, and alder-dyed Woodwardia for white, black, and red patterns respectively. All these plants appear to grow some distance south of the range of this basketry. At least in some places to the south they are undoubtedly sufficiently abundant to serve as materials. The limit of distribution of the art can therefore not be ascribed to botanical causes. Similarly, there is no easily seen reason why people should stop wearing basketry caps and pounding acorns in a basketry hopper because their materials or technique have become different. That they do, evidences the strength of this particular complex.

In southern California a definite type of basket ware is adhered to with nearly equal rigidity. The typical technique here is coiling, normally on a foundation of straws of Epicampes grass. The sewing material is sumac or Juncus. Twined ware is subsidiary, is roughly done, and is made wholly in Juncus a material that, used alone, forbids any considerable degree of finish. Here again the basketry cap and the mortar hopper appear but are limited toward the north by the range of the technique.

From southern California proper this basketry has penetrated to the southerly Yokuts and the adjacent Shoshonean tribes. Chumash ware also belongs to the same type, although it often substitutes Juncus for the Epicampes grass and sometimes uses willow. Both the Chumash and the Yokuts and Shoshoneans in and north of the Tehachapi mountains have developed one characteristic form not found in southern California proper: the shouldered basket with constricted neck. This is represented in the south by a simpler form, a small globular basket. The extreme development of the "bottle neck" type is found among the Yokuts, Kawaiisu, and Tübatulabal. The Chumash on the one side, and the willow-using Chemehuevi on the other, round the shoulders of these vessels so as to show a partial transition to the southern California prototype.

The Colorado river tribes slight basketry to a very unusual degree. They make a few rude trays and fish traps. The majority of their baskets they seem always to have acquired in trade from their neighbors. Their neglect of the art recalls its similar low condition among the Pueblos, but is even more pronounced. Pottery making and agriculture seem to be the influences most largely responsible.

Central California from the Yuki and Maidu to the Yokuts is an area in which coiling and twining occur side by side. There are probably more twined baskets made, but they are manufactured for rougher usage and more often undecorated. Show pieces are usually coiled. The characteristic technique is therefore perhaps coiling, but the two processes nearly balance. The materials are not so uniform as in the north or south.

The most characteristic plant is perhaps the redbud, Cercis occidentalis, which furnishes the red and often the white surface of coiled vessels and is used in twining also. The most common techniques are coiling with triple foundation and plain twining. Diagonal twining is however more or less followed, and lattice twining, single-rod coiling, and wicker work all have at least a local distribution. Twining with overlay is never practiced. Forms are variable, but not to any notable extent. Oval baskets are made in the Pomo region, and occasionally elsewhere, but there is no shape of so pronounced a character as the southern Yokuts bottleneck.

A number of local basketry arts have grown in central California on this generic foundation. The most complicated of these is that of the Pomo and their immediate neighbors, who have developed feather-covering, lattice-twining, checker-work, single-rod coiling, the mortar hopper, and several other specializations. It may be added that the Pomo appear to be the only central Californian group that habitually make twined baskets with patterns.

Another definite center of development includes the Washo and in some measure the Miwok. Both of these groups practice single-rod coiling and have evolved a distinctive style of ornamentation characterized by a certain lightness of decorative touch. This ware, however, shades off to the south into Yokuts basketry with its southern California affiliations, and to the north into Maidu ware.

The latter in its pure form is readily distinguished from Miwok as well as Pomo basketry, but presents few positive peculiarities.

Costanoan and Salinan baskets perished so completely that no very definite idea of them can be formed. It is unlikely that any very marked local type prevailed in this region, and yet there are almost certain to have been some peculiarities.

The Yuki, wedged in between the Pomo and tribes that followed the northern California twining, make a coiled ware which with all its simplicity cannot be confounded with that of any other group in California; this in spite of the general lack of advancement which pervades their culture.

It thus appears that we may infer that a single style and type underlies the basketry of the whole of central California; that this has undergone numerous local diversifications due only in part to the materials available, and extending on the other hand into its purely decorative aspects; and that the most active and proficient of these local superstructures was that for which the Pomo were responsible, their creation, however, differing only in degree from those which resulted from analogous but less active impulses elsewhere. In central California, therefore, a basic basketry complex is less rigidly developed, or preserved, than in either the north or the south. The flora being substantially uniform through central California, differences in the use of materials are in themselves significant of the incipient or superficial diversifications of the art.

The Modoc constitute a sub-type within the area of twining. They overlay chiefly when they use Xerophyllum or quills, it would seem, and the majority of their baskets, which are composed of tule fibers of several shades, are in plain twining. But the shapes and patterns of their ware have clearly been developed under the influences that guide the art of the overlaying tribes; and the cap and hopper occur among them.

It is difficult to decide whether the Modoc art is to be interpreted as a form of the primitive style on which the modern overlaying complex is based, or as a readaptation of the latter to a new and widely useful material. The question can scarcely be answered without full consideration of the basketry of all Oregon.

Cloth is unknown in aboriginal California. Rush mats are twined like baskets or sewn. The nearest approach to a loom is a pair of upright sticks on which a long cord of rabbit fur is wound back and forth to be made into a blanket by the intertwining of a weft of the same material, or of two cords. The Maidu and southern Californians, and therefore probably other tribes also, made similar blankets of feather cords or strips of duck skin. The rabbit skin blanket has of course a wide distribution outside of California; that of bird skins may have been devised locally.

Kroeber, A. L. Elements of Culture in Native California, University of California Press, 1922.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.