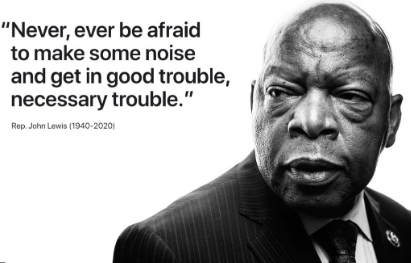

LOSING JOHN LEWIS

by Margo Macartney

The news of John Lewis's passing hit me like a ton of bricks. Even a week later, it was something I couldn't talk about without feeling like I was falling apart. I would start to say his name in the course of a simple unemotional conversation and choke up. If I kept trying to talk, my voice would falter, tears would well up and I'd relapse into silence, so as not to outright cry. Why was that?

A California white woman born three years before John Lewis, who never knew him. He was a Black Christian man. I knew him only from television news and print news, I wasn't even Christian. I'd left Christianity for Zen Buddhism years ago.

John Lewis represented the Last Great Man and touched something so deep inside me I didn't realize it was there. I always knew I admired him, thought he was a Giant of a Man. His cause was justice. I watched him, now in his seventies, lead the U.S. Congress in a sit-in on the Congressional floor in an effort to pass gun control legislation. He stood up for what was right, for what was just.

In the 1960s I watched him on television being beaten by police, and watched him stand up and refuse to be silenced. He would open his mouth again and again - that powerful mouth with its powerful words, always peaceful, and with love. He was nonviolent and utterly persistent. And his words found resonance in my soul, always.

In 1965 I was married to John P. We had been keeping company for about a year, and we thought we could make a marriage. We were young, he a very good looking Black man from Los Angeles. We lived in California, in Synanon, a totally integrated commune of ex-addicts who came in all colors and ages. From our tiny corner of the world, we were involved and part of the Civil Rights Movement. No matter that we were on a beach in Southern California.

Synanon had residences in Santa Monica, San Diego, San Francisco, Oakland, Marin County, Detroit and New York. People were shuffled in and out of these facilities depending on needs, and John and I made the rounds, coast to coast. And as we moved from place to place, we followed the speeches of Martin Luther King and the civil right movement and John Lewis..

Notwithstanding the fact that my brother had "disowned" me and made life difficult for my parents, on a daily basis John and I were protected from the societal backlash of a mixed race marriage. My parents and the rest of my family accepted John, and his family accepted me. Both families were gracious. My mother later told me they went to see the Hollywood movie "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" which she said gave them some perspective on their situation. They invited us for holidays and seemed to like John.

John and I actually lived in Synanon, with other inter-racial couples, and people of all shades living together. It was, as I said, a completely integrated community. People were forced by proximity to get to know one another. What we learned was that words brought down barriers if they were honest words. People's prejudices and preconceived ideas of others couldn't last long once people began engaging in real conversation. "Love has no color" was a popular concept.

At one point John and I were transferred to the San Diego facility, where John was the director. I did administrative work, but my first job was to find an apartment -- a place for us to live. I don't remember the exact year; maybe 1966. That was the first -- and actually the only -- time the White Movement hit me in the face during those years. I would find an apartment, bring John at the end of the day or when he had time, and it would have been rented. Over and over and over again.

When I discussed my frustrations with the San Diego community members, frustrations which had blossomed into a general hostility for all of San Diego, I found the local friends of Synanon in complete denial. "There's no racial prejudice in San Diego" they would exclaim, blindly, over and over and over again. They tried to persuade me that the apartments probably just got rented. I got tired of the conversation.

Eventually we did find an apartment with a lovely landlord. The landlord liked John and often engaged him in conversation. After we had lived there a while one day, he quietly asked about John's heritage. "I'm just curious," he said. John, with his abundant charm, laughed and said he was a mongrel and recited his roots, that included ancestors who were former slaves, a white grandmother and a grandfather from the Philippines. Our landlord laughed and said, "we're all mongrels, aren't we?"

By sometime in late 1967 John and I lived in a Synanon community in downtown Oakland, then a rundown poor and mostly black ghetto. The streets had boarded up businesses, drug trafficking obvious to the casual observer, winos drinking in doorways, sirens at night. In the middle of this poverty loomed a 13-story building that had once been a posh athletic club that we, Synanon, had purchased. We began to rehab the building, which had a swimming pool, a big kitchen and dining room and I don't know how many rooms, large and small.

Despite the poverty, the neighborhood also had some really, really good restaurants, among them soul food restaurants and Chinese restaurants, so small they only admitted ten or twelve people. Also, amazing to me, was a Chinese laundry where you could have your laundry done if you saved up WAM (walk around money) and pick it up clean, in a tidy blue paper wrapped bundle a few days later. I had never experienced anything like that before, nor have I since. On one corner was a big drug store, one of the big chain drug stores. We noticed the prices there were higher than at the same drug store in Beverly Hills. It was impossible not to notice the exploitation.

We were there to make a difference, to make Oakland and the world a better place. We began to work with the Black Panthers, who held Saturday morning pancake breakfasts for the Oakland community. We lived on donated food, and we shared it with them, to help with the breakfasts.

Young kids ran loose on the streets without adult supervision. They probably weren't abandoned. More likely their parents and family were working two jobs, had babies to care for, and adults had no time to watch the older kids.

We met with Oakland city and police officials, and we started a day program, after school during the school year, and all day during summers and vacations, inviting the kids, some as young as nine or ten, to come in and hang out in our building, as long as they were clean and carried no drugs. We were a curiosity in downtown Oakland, so there was plenty of interest.

They had to bring written permission from their parents to be on Synanon premises.

My husband John was in charge of that program. Most, but not all of the kids, were Black. We called them "Notions." I don't remember why, but it was the "Notions Program" (possibly because it was somebody's notion to do it). We fed them, taught them manners, let them swim in the pool, play pool at our table, under supervision, and shared our lives with them, giving them attention that they did not receive at home. We sat them down in our talking circles we called "games" to work out differences and allowed them to use their foul language to these circles. Other than that, we expected them to use polite language.

They were safe. We loved them. They were interesting, curious kids, and Synanon was full of life, creativity and vitality in those days. It was a healthy and thriving community of idealistic people who wanted to be involved in civic life and make a contribution. We were involved and full of enthusiasm.

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther king was assassinated. It was devastating to all of us, but more so to my husband John. We had followed and been inspired by Martin Luther King's words, convinced that his prophecy, bending the long arc of the universe toward justice, would prevail and the world would find justice, and we imagined we were part of that vision.

John didn't talk a lot about King's death. He would mention it in synanon games, the talking circles we sat in twice a week, but the issue was bigger and had affected him more deeply than I had realized. It ate at him. At the time, he was working in a business venture Synanon had, Synanon Industries, selling pens and pencils and ad specialties to businesses all over the country. Synanon Industries was a step away from the original mission.

One day the following year, he solemnly told me he was leaving Synanon. He did not ask me join him. He told me his people needed him. I was stunned. My own defense mechanisms never immediately kick in. I freeze. I had no idea what to do or say. I was hurt, angry and immobile. He left almost immediately. I walked around wounded and emotionally bleeding for months.

We had of course known we were a mixed race couple, but race was a minor issue in our lives. Our battles were the same ego battles that all couples face. One day in the middle of an argument about something we started to laugh because we realized it wasn't us, it was my mother and his father in a battle, and it made us laugh. People accepted us as a couple. But the race issue was there, like a spectre in the background, whether we acknowledged it or not.

A couple of years ago I received an unexpected email from Wendell, a now grown up Notion in his fifties with his own family. Wendell moved into Synanon when he was eighteen, without ever having used drugs. He is now a social worker in northern California. In his letter he thanked me for the attention I paid to him when he was a kid, and told me how much that attention meant to him, how important it was, and how it changed his life. He explained it was attention he could not get at home. It was humbling to me, as I hadn't realized I'd given him all that much attention.

The end of my marriage did not end my interest in justice or in civil rights. I went to law school after I left Synanon. I worked for years as a public defender. I viewed my job as holding the prosecutor's wings to the wall to make sure the evidence against my client was valid, which sometimes was, and sometimes not. I was successful in getting some cases dismissed because of insufficient evidence. Even if my client was guilty, often the case, my aim was to keep the punishment reasonable. Many of my clients were from Mexico, the crimes they faced involved moving drugs across the border.

I no longer practice law, other than a sporadic case for a friend. I’ve devoted my time to art, in particular, ceramics. The photograph of the bust at the begining ofthis article is still drying. When it is dried and fired, I’ll replace what’s there with a photo of the finished piece.

I've remained politically involved, marched with others carrying signs, protesting injustice. Now that I'm officially "old", I just park myself with signs, supporting Black Lives Matter, keeping the post offices open, and urging people to vote. John Lewis always continued as an inspiration. And now he is no longer here.

Perhaps John Lewis's departure brought back memories of a time when I was young, idealistic and part of a movement the make the world a better place. Perhaps the sadness of his passing was so overwhelming because after all his work, after all everyone's work, the rise of White Supremacy, the conspiracy theories of Qanon, and racial wars are still so incredibly pervasive in our American society.

What is for sure: John Lewis left us with work to be done. If we learned nothing else from him, it was never ever to give up.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.