Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Livy, Vol III. by Livy, translated by George Baker, 1833.

To this division of my work I may be allowed to prefix a remark, which most writers of history make in the beginning of their performance: that I am going to write of a war, the most memorable of all that were ever waged; that which the Carthaginians, under the conduct of Hannibal, maintained with the Roman people; for never did any other states and nations of more potent strength and resources engage in a contest of arms: nor did these same nations at any other period possess so great a degree of power and strength.

The arts of war also, practised by each party, were not unknown to the other; for they had already gained some experience of them in the first Punic war; and so various was the fortune of this war, so great its vicissitudes, that the party, which proved in the end victorious, was at times brought the nearest to the brink of ruin. Besides, they exerted in the dispute almost a greater degree of rancor than of strength, the Romans being fired with indignation at a vanquished people presuming to take up arms against their conquerors; the Carthaginians, at the haughtiness and avarice which they thought the others showed in their imperious exercise of the superiority which they had acquired.

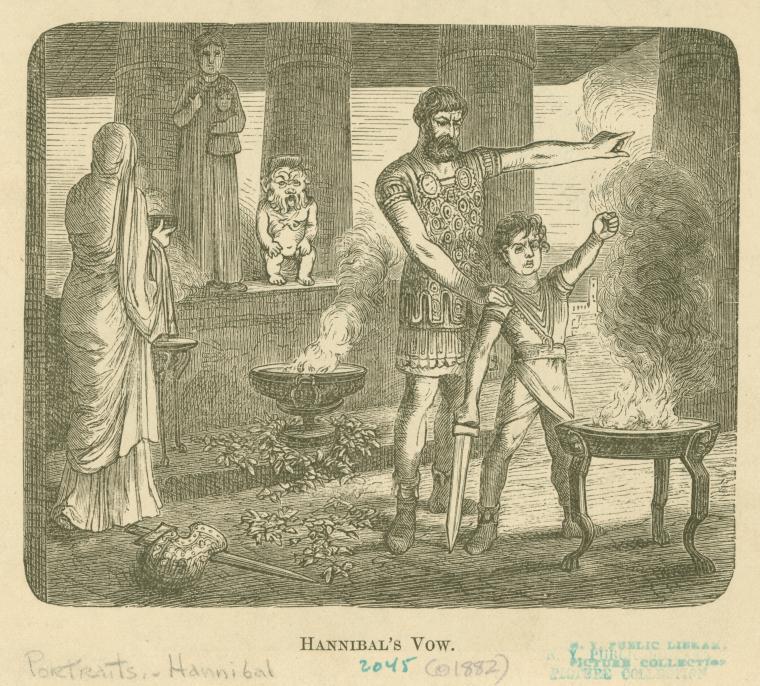

We are told that when Hamilcar was about to march at the head of an army into Spain, after the conclusion of the war in Africa, and was offering sacrifices on the occasion, his son Hannibal, then about nine years of age, solicited him with boyish fondness to take him with him, whereon he brought him up to the altars, and compelled him to lay his hand on the consecrated victims, and swear that, as soon as it should be in his power, he would show himself an enemy to the Roman people. Being a man of high spirit, he was deeply chagrined at the loss of Sicily and Sardinia; for he considered Sicily as given up by his countrymen through too hasty despair of their affairs, and Sardinia as fraudulently snatched out of their hands by the Romans during the commotions in Africa, with the additional insult of a farther tribute imposed on them.

2. His mind was filled with these vexatious reflections; and during the five years that he was employed in Africa, which followed soon after the late pacification with Rome, and likewise during nine years which he spent in extending the Carthaginian empire in Spain; his conduct was such as afforded a demonstration that he meditated a more important war than any in which he was then engaged; and that, if he had lived some time longer, the Carthaginians would have carried their arms into Italy under the command of Hamilcar, instead of under that of Hannibal.

The death of Hamilcar, which happened most seasonably for Rome, and the unripe age of Hannibal, occasioned the delay. During an interval of about eight years, between the demise of the father, and the succession of the son, the command was held by Hasdrubal; whom, it was said, Hamilcar had first chosen as a favorite, on account of his youthful beauty, and afterwards made him his son-in-law, on account of his eminent abilities; in consequence of which connexion, being supported by the interest of the Barcine faction, which among the army and the commons was exceedingly powerful, he was invested with the command in chief, in opposition to the wishes of the nobles. He prosecuted his designs more frequently by means of policy than of force; and augmented the Carthaginian power considerably by forming connexions with the petty princes; and, through the friendship of their leaders, conciliating the regard of nations hitherto strangers. But peace proved no security to himself.

One of the barbarians, in resentment of his master having been put to death, openly assassinated him, and being seized by the persons present, showed no kind of concern; nay, even while racked with tortures, as if his exultation, at having effected his purpose, had got the better of the pains, the expression of his countenance was such as carried the appearance of a smile. With this Hasdruhal, who possessed a surprising degree of skill in negotiation, and in attaching foreign nations to his government, the Romans renewed the treaty, on the terms that the river Iberus should be the boundary of the two empires, and that the Saguntines, who lay between them, should retain their liberty.

3. There was no room to doubt that the suffrages of the commons, in appointing a successor to Hasdruhal, would follow the direction pointed out by the leading voice of the army, who had instantly carried young Hannibal, to the head-quarters, and with one consent, and universal acclamations, saluted him general. This youth, when scarcely arrived at the age of manhood, Hasdruhal had invited by letter to come to him; and that affair had even been taken into deliberation in the senate, where the Barcine faction showed a desire that Hannibal should be accustomed to military service, and succeed to the power of his father.

Hanno, the leader of the other faction, said, ‘ Although what Hasdrubal demands seems reasonable, nevertheless, I do not think that his request ought to be granted and, when all turned their eyes on him with surprise at this ambiguous declaration, be proceeded: ‘Hasdrubal thinks that he is justly entitled to demand from the son the bloom of youth which he himself dedicated to the pleasures of Hannibal’s father. It would however be exceedingly improper in us, instead of a military education, to initiate our young men in the evil practices of generals. Are we afraid lest too much time should pass before the son of Hamilcar acquires notions of the unlimited authority, and the parade of his father’s sovereignty; or that after he had, like a king, bequeathed our armies as hereditary property to his son-in-law, we should not soon enough become slaves to his son? I am of opinion that this youth should be kept at home, where he will be amenable to the laws and to the magistrates; and that he should be taught to live on an equal footing with the rest of his countrymen; otherwise this spark, small as it is, may hereafter kindle a terrible conflagration.’

4. A few, particularly those of the best understanding, concurred in opinion with Hanno; but, as it generally happens, the more numerous party prevailed over the more judicious. (Hannibal was sent into Spain, and on his first arrival attracted the notice of the whole army. The veteran soldiers imagined that Hamilcar was restored to them from the dead, observing in him the same animated look and penetrating eye; the same expression of countenance, and the same features. Then, such-was-his-behavior, and so conciliating, that in a short time the memory of his father was the least among their inducements to esteem him. Never man possessed a genius so admirably fitted to the discharge of offices so very opposite in their nature as obeying and commanding: so that it was not easy to discern whether he were more beloved by the general or by the soldiers. There was none to whom Hasdrubal rather wished to intrust the command in any case where courage and activity were required; nor did the soldiers ever feel a greater degree of confidence and boldness under any other commander.

With perfect intrepidity in facing danger, he possessed, in the midst of the greatest, perfect presence of mind. No degree of labor could either fatigue his body or break his spirit: heat and cold he endured with equal firmness: the quantity of his food and drink was limited by natural appetite, not by the pleasure of the palate. His seasons for sleeping and waking were not distinguished by the day, or by the night; whatever time he had to spare, after business was finished, that he gave to repose, which however he never courted, either by a soft bed or quiet retirement: he was often seen, covered with a cloak, lying on the ground in the midst of the soldiers on guard, and on the advanced posts. His dress had nothing particular in it beyond that of others of the same rank; his horses and his armor he was always remarkably attentive to and whether he acted among the horsemen, or the infantry, he was eminently the first of either, the foremost in advancing to the fight, the last who quitted the field of battle.

These great virtues were counterbalanced in him by vices of equal magnitude; inhuman cruelty; perfidy beyond that of a Carthaginian; a total disregard of truth, and of every obligation deemed sacred: utterly devoid of all reverence for the gods, he paid no regard to an oath, no respect to religion. Endowed with such a disposition, a compound of virtues and vices, he served under the command of Hasdrubal for three years, during which he omitted no opportunity of improving himself in every particular, both of theory and practice, that could contribute to the forming of an accomplished general.

Livy. Livy, vol III. translated by George Baker, A. J. Valpy, 1833.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.