Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

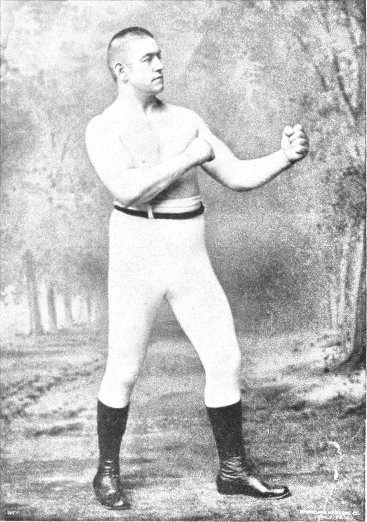

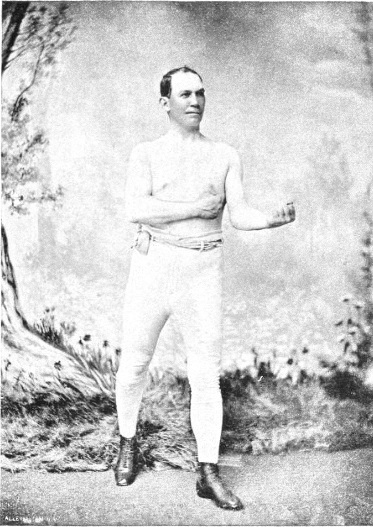

“Boyhood and Boxing Beginnings” from Life and Reminiscences of a 19th Century Gladiator by John L. Sullivan, 1892.

“Are you going to stay caged up here all day?"

''Yes; rather than run the gauntlet of the gang laying for me in front of your hotel. Do you know if I ventured out there now I would be grabbed by the arms and legs and almost pulled to pieces by fellows that want to feel my muscle?"

The scene was in a Western city, and was one of many encountered by the speaker.

''That's him sure." "No." "I tell you he went up that way." "Big?" "You bet. Hold on till he

comes down,"—were some of the ejaculations heard from the crowd that swayed in the office and surged in the street.

"Why, I am not safe even in this private room. Only a little while ago the door was opened with a bang and a chap with a tragic stride and stagy voice"—

"Is it him?" was the interruption just at that moment from a gawky looking Paul Pry, who peered through the door. “Is it him?"

The bent of his curiosity seemed to have turned his nose into a corkscrew and his neck into an interrogation mark.

“It is him—now go."

In spite of this assurance he continued in a kind of litany, with ''Is it him?" until, in a moment when he had just reached “Is it"—the "him" rose with the rage of Hercules crushing the hydra and hurled the animated question from the room.

"It is him!" was heard in the hallway, and between the sounds of halting steps, and as he stumbled down the stairs his words arose like the ''Excelsior" of the Alpine youth, ''It is him!"

This is the style in which they tell of the curiosity to see the champion out West, and it may be taken as a sample of what has met him during his career with all degrees of dignity, from that of the Prince in England to the native in Samoa.

The author, now that he has decided to round out the career which gave rise to it, does not desire to remain any longer "caged up," but to present himself as far as he may be of interest on the printed page.

"Oh, that my adversary would write a book," was the saying of one who believed that an author always makes himself a mark for attack. In spite of this I am willing for once to drop my guard, ceasing to lead off, to feint, to fib, to duck or ward, allowing my head to be held in chancery between the covers of a book, and yet looking for lively cross-counter dealings.

I was born on the 15th of October, 1858, in Boston, my parents then occupying a house on Harrison Avenue, nearly opposite Boston College, the location being about that of the new Homoeopathic Dispensary. Here we lived until I was ten years of age, when we moved, successively, to Parnell and Lenox streets and Boston Highlands.

My father was a native of the town of Tralee, in County Kerry, Ireland, and my mother of, Athlone, in County Roscommon. Both are now dead. The remainder of the family are a sister and a younger brother.

As I am the only one who has been noticed for size or strength, people have sometimes been curious to know from whom mine came, particularly as my father was a small man, being only five feet three and one half inches, and never weighing more than one hundred and thirty pounds. My mother was of fair size, weighing about one hundred and eighty pounds, and some have given the credit to her.

One writer, after I had grown in reputation as an athlete, said: “Sullivan derived all his great physical strength from his mother, who in her youth was considered a woman of remarkable physical and mental powers." Whatever there may be in this, it should be borne in mind that my uncles and the other relatives of my father in Ireland were all large men, and were known in their section of the county by a Celtic word which might be translated as "the big Sullivans."

Here it may not be improper to mention the great family of Sullivans known in American history, as their father came from the same spot as mine, to settle in the same part of this country, and as they were remarkable for size and muscular strength, in addition to their powers as governors, generals and judges. John Sullivan was in 1774 a member of the first General Congress. In December of that year he took a leading part in the daring achievement of a party of American patriots who rowed by moonlight to the British fort, William and Mary, near Portsmouth, overpowered the force, and captured a hundred barrels of powder that were afterwards used at Bunker Hill. In this way a Sullivan has received the honor of striking the very first blow of the Revolution.

During the Revolution he was regarded as one of the most trusty officers in the service of Washington and was by his side on the Christmas Eve of 1776 when he crossed the Delaware and routed the British. After the success had been gained he was made Governor of New Hampshire.

Governor James Sullivan of Massachusetts, his brother, was one of the commissioners appointed by Washington, to settle the boundary lines between the United States and the British Provinces. His son of the same name was a man of physical as well as mental strength, and won reputation as a judge.

John L. Sullivan, another son of the governor of Massachusetts, possessed high ability, especially in science and engineering. He constructed the great Middlesex canal, which was the connection between Massachusetts and New Hampshire before railroads; and he also invented the first steam tow-boat, for which he was awarded a patent in preference to the famous Fulton.

The mother of the two Governor Sullivans, as might be expected, was a woman of much spirit. There is a story told of a visit which she paid to the governor of Massachusetts when he had as his guest his brother, John, of New Hampshire. The servant, not knowing her, informed her coldly that she could not see the governor—he was engaged.

"But I must see him," exclaimed the old lady.

“Then, madam, you will please wait in the anteroom."

"Tell your master," said she, sweeping out of the hall, “that the mother of two of the greatest men in America will not wait in anybody's anteroom."

The Governor having called his servant, on hearing the report said to his brother, “Let us run after her; it's mother for certain.” Accordingly the two governors sallied out, and soon made amends for her offended dignity.

Like almost all Boston boys I was given good opportunities for education. I was first sent to the Primary School on Concord Street. My teacher there was Miss Blanchard, a lady that stood no nonsense from any of the boys. But she was good hearted and had as much interest in the poorer class of children as she had in the upper ten. After going through the primary school I went to the Dwight Grammar School on Springfield Street and graduated. I attended night school at the old Bath House, Cabot Street, which was afterwards turned into a voting place election house. I never had much trouble with the teachers in any of my school experience.

Miss Jones, of the grammar school, sent me one day for my medicine which I received at the hands of my old friend, Jimmy Page, who was principal or head master of the school. That was the only time that I ever had to take the rattan, which I did like a little man. It was commonly taken for granted that if a boy cried he was a weak one. I guess I wanted to cry but I couldn't, although he gave me what I deserved; and I was quite a hero after that among the other boys'.

During my school years in spare time and after school I played ball, marbles, spun tops, and did everything of the kind that boys do. I had no occupation to take up my attention after school hours, and of course went through all the sports that boys go through at that time of life.

As to my studies I took better to mathematics than I did to anything else, and I was always on the lookout to avoid geography when it was geography day. My travelling experience has since given me more real facts about geography than I could have learned in a book in ten years. In school days I had many a fracas with the other fellows, and I always came out on top.

After leaving the Public School I went to Comer's Commercial College, and attended about one year. From that I went to Boston College, Harrison Avenue, where I studied about sixteen months. It was the desire of my parents to have me study for the priesthood, but it was not mine.

My first work was in the plumbing trade with the firm of Moffat & Perry. In those days it was the custom with boys, generally, when they wanted to become apprentices, to be bound to a trade by their father; in other words a man signed a written contract to teach the trade so that the boy would become a master mechanic after learning the business. I had gone for a situation, and as I thought I would like plumbing, I got a position for myself I worked at the plumbing trade for six months.

When the water pipes in the old Williams Market, which had an armory overhead, at the corner of Dover and Washington streets, were frozen, a journeymen and myself were sent there. We went with all the necessary appliances which were used for thawing out pipes in the plumbing business, including a lighted torch and hot water, and after a half day's work at that, the journeyman and myself had some words, in which I told him that I thought I had carried water enough and that he could have a few hours at that work himself. This caused some feeling between us and resulted in our having a scrap over the affair, and he made his escape to the shop, which was only a few doors from where we were working. I was paid $4.00 a week for being an apprentice. The journeymen at that time were paid all the way from three to six dollars a day.

Naturally, after I left school, I joined base-ball nines, among which were the Tremonts, Etnas, Our Boys, and several other clubs. As I was considered a pretty good base-ball player, I had been offered $1,300 if I would play ball for the Cincinnati Club in the years 1879 and 1880.

I left the plumbing to learn the trade of a tinsmith with James Galvin, corner of Warren and Dudley streets, for whom I worked eighteen months, and quit on account of disagreement with a man who worked on the same bench, who had just become a journeyman as I became an apprentice. Then I went to playing baseball again with different amateur clubs.

The first time I ever put a boxing glove on was at a variety entertainment at Dudley Street Opera House, Boston Highlands; and when I went to the entertainment I did not expect to be called upon to do that; but at that entertainment there was a strong young fellow named Scannell, who stated to the audience that he was anxious to meet me or any one in the audience. I had the reputation of being able to hold my own with any young man, and, after considerable talking one way and the other, they asked me to put on the gloves with Scannell. I did not want to do so, but finally consented.

I was working at tinsmithing then, and had no tights nor had made any arrangements for boxing, but simply took off my coat, rolled up my shirt sleeves, and put on the gloves. When we put up our hands, he hit me a crack on the back of the head, and the first thing I did was to punch him as hard as I could, knocking him clean over the piano which was on the stage. This was the first actual experience of mine at boxing, and I will never forget this experience, nor do I think he will.

I quit my trade as a tinsmith because I could not agree with the journeyman who worked on the same bench with me. We argued a great many different subjects; about dogs, game cocks, base-ball, and anything and everything in sporting circles, and a great many other things. We never could agree on anything, because he claimed he always had something better than anybody else. His dogs were better than any I had ever seen; his game cock was better than any I had; in fact, anything I had was no account, and his was number one. Our quarrels and arguments kept up quite a while until finally he said one day something about proving to me that I was wrong, and wanted to fight it out to prove it; and when I said, "All right; come out into the yard," he quit, and would not go. If ever I wanted to lick a man in the world, he was that one, and I would have given a good deal if he only would have come out.

From that I went to the mason's trade, at which I worked about two years and learned that on account of having a better opportunity, as my father used to work at the business.

I played amateur base ball with a great many teams before I took to boxing. I was paid twenty-five dollars a game for playing with the Eglestons, of which they would play two games a week, — Wednesdays and Saturdays. For them I played principally first base and left field, although I could play in any position.

At the age of nineteen, I drifted into the occupation of a boxer. I went to meet all comers, fighting all styles and all manner of builds of men, until the present day. I never was taught to box; I have learned from observation and watching other boxers, and outside of that my style of fighting is perfectly original with me. Some one has said that old Prof. Bailey claimed the credit of teaching me, but he was wrong in the assertion, as I never took a boxing lesson in my life, having a natural ambition for the business.

I was always a big fellow, weighing two hundred pounds at the age of seventeen, and I had the reputation for more than my proportionate share of strength.

I remember one time of a horse car getting off the track on Washington Street, and six to eight men trying to lift it on. They didn't succeed, and so I astonished the crowd by lifting it on myself. I used to practise such feats as lifting full barrels of flour and beer, or kegs of nails above my head, but I gave up those things as I found that men who did feats of strength made themselves too stiff for any good boxing. I could lift a dumb-bell with the best, but I do not use more than a two pounder, as it is nimbleness and skill that a boxer needs.

It was on account of these feats that I first got the name of “Strong Boy." There was a light boxer

named Fairbanks that I called “Billy-go-lightly," and he replied by calling me '' John, the Strong Boy."

Now that I have touched on the subject of nicknames, I may as well give a little list of titles that have been given to me after various victories in the ring, not with the idea that I endorse them myself; but that — "A little nonsense, now and then. Is relished by the wisest men."

"The Boston Hercules." ''Knight of the Fives." "The hard-hitting Sullivan." "The Boston Miracle of huge muscles, terrific chest and marvellous strength." "The king of the ring." "The youthful prince of pugilists. "The magnificent Sullivan." "Boston's philanthropic prize-fighter." "Young Boston giant." "The finest specimen of physical development in the world." "The terrific Boston pugilist." "Trip-hammer Jack." "Spartacus Sullivan." "The king of pugilists." "Monarch of the prize ring." "The scientific American." "Hurricane hitter." "Mighty hero of biceps." "His fistic Highness." "Champion of champions." "Boston's pet." "Boston's pride and joy." "The cultured slugger." "Sullivan the Great." "The Napoleon Bonaparte of sluggers." "King of fistiana." "Sullivan the wonder." "The champion pounder." "Professor of bicepital forces." "Prize-fighting Caesar." "The Hercules of the ring." "The Goliath of the prize ring." "Americans invincible champion." ''A champion who never knew defeat."

Whatever I have attempted to do, I have always looked on the bright side, that is to say, that there is nothing I have undertaken to do, since I have reached the age of understanding, in which I have not made it a point to be successful. When going into a ring, I have always had it in my mind that I would be the conqueror. That has been my disposition particularly as to my fighting propensities.

The first time I ever started to spar in public with any noted man of reputation was with Johnny Woods, better known as "Cockey Woods," in Cockerill Hall, Hanover Street, Boston, in 1878. He was a resident of Boston, and was a big man who once was matched to fight Heenan, ''The Benecia Boy." I soon disposed of him.

The following year, 1879, I sparred with Dan Dwyer, in Revere Hall, corner of Green and Chardon streets. He was considered a strong boxer. I had the best of the encounter, and surprised a great many of the wise ones who thought I would not be in it, as he was called "the champion of Massachusetts."

Another victory gained by me in those days was over Tommy Chandler, one of the "old timers," but not the "Tom" of Pacific coast fame.

I sparred with Prof. Mike Donovan at the Howard Athenaeum at his benefit, given him by his management and friends, in Boston, in which I wound up with him in three rounds and endeavored to knock him out, when the master of ceremonies made us shake hands and we departed to our dressing rooms. In a conversation which took place while we were upstairs, he said to me: ”You tried to knock me out," and I replied, "No, I did not try very hard."

He said, “Well, I will be honest, I tried to knock you out."

I then told him "I tried to knock him out and if I had landed it would have been all day with him."

When he went back to New York he said to Joe Goss, Geo. Rooke, and all the knowing ones, that there was a fellow up in Boston by the name of Sullivan, who, in his estimation, was going to be the boss of them all.

Jack Hogan, of Providence, was another candidate who shared the fate of those mentioned.

The following year, 1880, on the sixth day of April, I demonstrated to the wise ones that I was to become to the world one of the greatest exponents of the manly art, by disposing of one of England's greatest champions, Joe Goss, at a testimonial given to him by his numerous friends at Music Hall, Boston, in which we sparred three rounds. In the second round I dealt him a blow which virtually ended the contest. Goss was given time to recover, and through the advice of Tom Denney and Billy Edwards, I sparred the last round without trying to knock him out, which I could have done. After this he was heard to remark that my blows were like “the kicks of a mule."

A writer describing the affair at the time said, —

"Sullivan's terrific hitting on this occasion created quite a sensation."

Now one word about old Joe Goss. As a pugilist and a boxer, he was a gentleman in every respect, being of a kind-hearted, social, and of a genial disposition, and beloved by every one who knew him. I have seen Goss put his hand in his pocket to assist the needy, and one of his great hobbies was always to fondle and caress the little ones, of whom he was a great lover. From the first time we became acquainted, which was on the occasion of our boxing together, at his benefit, we became warm and personal friends, and continued so until the hour of his death.

Sullivan, John L. Life and Reminiscences of a 19th Century Gladiator, Geo. Routledge & Sons, 1892.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.