Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

“Ethical Culture and Physical Training” from Pre-Meiji education in Japan; a study of Japanese education previous to the restoration of 1868 by Frank Alanson Lombard, 1913.

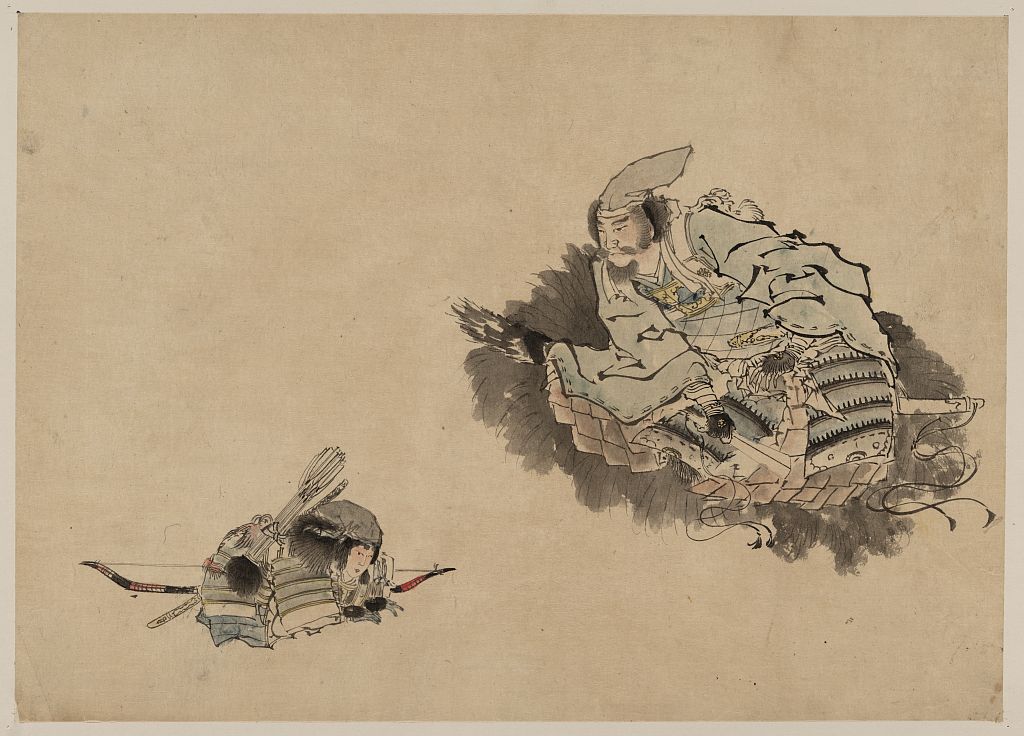

In Feudal Japan society was divided into classes. At the head of these stood the samurai. It is hardly fair to call them soldiers for, although they were soldiers, they were far more. During the Shogunate, which was pre-eminently the period of samurai supremacy, they practically monopolized the educational opportunities afforded by the schools of the government ; but one phase of their education is worthy of separate consideration. Their military training, however specialized in the case of individuals, was never narrowly special in character. Physical in form, it was ethical as well as physical in intent, and a recognized means of ethical culture. The Japanese have been considered a warlike, war-loving people.

Such they are not. Rather are they a people of high spirit who have been led at times to manifest that spirit in the activities of war. When history is made the record not alone of government changes, wrought so frequently in tumult and blood-shed, but also of the cultural efforts of individuals and society, it is clearly seen that war has played an insignificant part in the development and progress of the Japanese people. Their attainments have been the attainments of peace; and the form of their ancient military training had for its goal culture of soul as inseparable from that of body.

Martial valor seems to have characterized the exploits of Japan's pre-historic days. The names of many of her ancient deities have reference to strife. The land was created or drawn from the foam of the sea by Izanagi and Izanami with a spear; and a sword was among the sacred gifts granted unto the Imperial House by the Sovereignty of Heaven. The name Bushi, or Buge, designating a warrior class, is of ancient origin, first appearing in an Imperial edict of between 715 and 724 A.D. Such a class, as distinct from the mass of the people, developed gradually and naturally, at a time of Imperial weakness when a few families, notably the Fujiwara, had gained a monopoly of influence and discouraged martial valor that they might the more easily rule an effeminate court. Weakness at the Imperial centre compelled the outlying clans, each in self-defence, to train a body of soldiery. Of the clans practicing thus the arts of war, the Minamoto became most powerful and, overthrowing the Fujiwara supremacy, led the way to the Shogunate.

The rule of the Shogunate was a military usurpation but in character it varied greatly under successive leaders. At its best, while exercising an authority quite independent of the Throne, it was, as a matter of fact, a saving sovereignty, preserving the nation and the Throne against their own degeneracy; and at its worse, it but fell before the temptation of great power, seeking to continue those sad circumstances which made the exercise of its power a national necessity. Thus among the professions of old Japan none, through long periods of history, held higher honor than that of the soldier, the samurai, the defender of authority whose crowning virtue was personal loyalty and whose calling was that of a gentleman.

In considering the education of this gentleman, we notice certain points of likeness to that received by the knight of Mediaeval Europe. The education of the samurai was primarily a family education, which varied naturally in scope with the standing of the family but which in every case was characterized by certain distinguishing features. The child of a noble warrior was from infancy placed under the care of a nurse who by culture and training as well as by birth was fitted to be his governess. Later he was given into the direction of a male tutor from among the foremost of the associated samurai. Children of less exalted birth had fewer educational advantages; but family training was given to all in graces according to the social code, in physical skill through athletic exercises, and in character by means of both. Perhaps the most remarkable feature of this education was its emphasis which was placed first upon character, second upon skill, and last of all upon mere knowledge.

This education began in childhood and was for the whole life, not for that fraction thereof which might be spent upon the battle-field. Bushido, never formulated, and defying definition, was the way of the warrior, and by that way he was to walk daily. His education consisted in the practice of that way. "Bushido" says Dr. Nitobe, "is the code of moral principles which the knights were required or instructed to observe. It is not a written code, at best it consists of a few maxims handed down from mouth to mouth or coming from the pen of some well-known warrior or savant. More frequently it is a code unuttered and unwritten, possessing all the more the powerful sanction of veritable deed, and of a law written on the fleshly tablets of the heart. It was founded not on the creation of one brain, however able, or on the life of a single personage, however renowned. It was an organic growth of decades and centuries of military career."

Thus Bushido was an ethical spirit; and it is significant that in connection with the training of the warrior class we find most conspicuous no manual of arms but an unwritten principle of honor, the more vital, perhaps, for having escaped the systematization which blighted Japanese organized education.

Social graces are not readily associated with the education of a soldier; but, while the samurai scorned the effeminacy of the court nobles, he regarded the poise and perfection of an elaborate ceremonial of conduct as conducive to that poise and perfection of soul which should characterize a soldier, and without which he might in moments of passion be tempted into loss of self-control and so into unbecoming conduct. Etiquette was taught with strictness not alone or chiefly as a form of conduct appropriate in dealing with others but as a means of self-discipline in that which befitted self. However polite the Japanese may be in expressed consideration for the feelings of others, the samurai was ceremonious from a sense of what was becoming to a man in his position, and the punctilious observance of all forms was a matter of no light importance in his educational training. His athletic sports and military exercises were all prefaced and concluded by ceremonial conduct, almost ritualistic in character, while his accomplishments often appeared little more than forms which in themselves, apart from the poise and control through them attained, were vain and foolish.

Courtesy and conduct, under all circumstances, were taught concretely in the actual training of daily life from which there was no escape for the forgetful. Children with parents and with their companions were constantly under discipline which habituated conduct and made certain reactions a matter of instinct. Stories of daring and of ideal heroism were the stuff on which children's imaginations were fed; and feats, often beyond childish strength, were required that drill might set the ideal as a part of daily living and not as something to be rightly expected only of the remote and unusual. The writer remembers the son of a twosworded samurai telling how, when as a lad he had been given his sword and was supposed to learn its use and avoid its misuse, he sat down to dinner one day next his aged grandfather, and, in boyish haste, laid his sword upon the wrong side, where it could not naturally be drawn quickly. Like a flash the old man's blade was forth, and the lad lay senseless by a blow from its flat surface that he might learn, in a way not to be forgotten, where to place a sword that might be needed in self-defense.

"Tis not in hatred that we beat

The bamboo bending neath the snow."

Neesima, Japan's Christian educator, himself a samurai, says: "My grandfather paid special attention to my education. Every evening he put me on his lap and told for me instructive stories about ancient heroes, great personages, wise men, etc., and above all, he was particularly attentive in instructing me to be obedient to parents and faithful to friends and at the same time to be careful in speaking, modest in act, and not to steal nor deceive and flatter." He also says that once when his grandfather heard of his disobedience to his mother, the old man caught the boy and rolled him up in a night coverlet and shut him up in a closet, later releasing him with tender words of explanation.

Outside of the home, even during the Dark Ages of Japan's history, the children of samurai were taught in the temple schools and in private institutions. During the period of increased attention to education under the Tokugawa, they enjoyed greater opportunities for literary culture; but book-learning was never highly valued by the true samurai whose intelligence rejoiced rather in deeds than words. His education often included poetical composition and familiarity with Confucian ethics; but he was primarily a man of action and regarded philosophy only as an aid to character and literature as an amusement. By far the greater number of the samurai received no formal literary training; yet they were trained men.

Training in the art of fencing, archery, jiujitsu, horsemanship and the use of the spear formed the bulk of their education outside of the home. It was severe; and each exercise, apart from skill, was supposed to impart some culture of character. For example, archery developed that composure of nerve which has very direct relation to self-control; and the very essense of jiujitsu consists in self-restraint which allows the foe to injure himself by his own unchecked onslaught.

Such was the emphasis placed upon self-control that it would seem that the samurai must have realized some great temptation to passion within his native character. The Japanese have been called stoical. Rather by nature they are strongly emotional, while their stoicism has been acquired by training. No one can deny the stoic element. It is most apparent in all the common experiences of life and upon occasions of great crisis; yet it is not the stoicism of the unfeeling but of those trained to control their feelings under all circumstances for which they can have been prepared. The unusual at times reveals the fire, and the restraint once broken often proves the strength of the passion which had been held in check.

The place in which the samurai were taught athletics was called dojo, the place for learning the way of the warrior. The strictest forms of etiquette were observed; and one who had completed the dojo training was an expert not only in military science as then understood, but also in that control which makes for character. As Waterloo is said to have been won upon the playground of Eton because of the self-mastery rather than because of the physical prowess there gained, so many a Japanese battle was determined by the moral qualities rather than the military skill derived from some teacher who made his training-field a place of manhood-culture. The culture of the will through muscular training, but recently recognized in theory, was among the samurai of Japan a seemingly intuitive practice. Data upon the subject do not allow definite conclusions, but they at least suggest the possibility that something of the samurai's moral strength had origin in his physical training through half a millenium.

All warriors of note, and many of humble station, had personal kaho, or private codes of conduct, which stood in lieu of any generally accepted standard of morality. These were often unified into a body recognized as binding within certain clans. The simple life of physical austerity and self-control was always a primary demand. Mutual confidence and trust between fellow-samurai was expected; and honor was supposed to govern all, including the final act of death. As typical of the shorter codes, prepared by samurai leaders for their followers, may be given the substance of seven articles issued by Kato-Kiy omasa, a loyal adherent of the House of Tokugawa:

Rise early, practice archery.

For amusement, hunt and wrestle.

Eat no white rice, eat the black.

Spend not for luxury; save, for public necessity.

Care only for the sword, they that dance and sing shall be slain.

Train in military tactics, avoid literary exercises.

That which was rightly to be expected was considered obligatory. The rightful expectation, not of others but of one's self, was the highest law. Self-respect was an essential of the samurai. Death was preferable to dishonor, the dishonor which, regardless of the opinion of others, was no less a deadly shame because secret within the hall of self-judgment,

'To-day the cherries are blooming;

To-morrow scattered they lay;

Their blooms are like to the warrior,

Whose life may end with the day;

Yet strives he ever unfailing,

His name in honor to stay.'

The cherry of Japan, unlike that of the West, is treasured not for its fruit but for its bloom. The blossoms open before the leaves appear, covering the branches and minutest twigs with a garment of glory which falls, after but a day or two of prime, at the slightest touch, at the silent call of the air, calmly, quietly, willingly, though it would seem passing to an untimely doom. So should the samurai go to meet the end when it comes after glory. The custom of harakiri, frequently practiced by men and by women of the samurai class, has been misunderstood. Though employed as a refuge and escape by many unworthy spirits, it was, on the part of the trained samurai, never an act of passion, never an act of fear, but always of calm resolve and from a sense of duty, a sacrament of truly religious significance in which self and all self-interest was not forgotten but deliberately laid aside in the interest of some high obligation. Self-inflicted death for any reason of self alone was never honored; but from childhood the samurai lad was trained to look upon death in calmness with open eyes and to control every emotion of fear in its presence.

Girls of a samurai family were not neglected, for, however inferior their position according to the teachings of current philosophy, they were to be the mothers of men and of samurai. Inured to physical virtues that were of masculine character, death was preferable to dishonor; and the samurai wife was one in whom her husband might well trust. As rulers within the home, they were to mold the ideals and superintend the early training of the children. This made it imperative that they should have standards of virtue and honor becoming the mothers of men, and gave added importance to their own familiarity with the art of fencing and the use of the naginata (long handled sword).

The attention paid by the samurai of old to the physical culture of his daughters, as mothers of sons to be, may in a measure be paralleled by the recent regard for physical training in the girls' schools of the Empire, Without any declared purpose on the part of the government, many recognize an intent looking not alone to the immediate hygienic effects but to the development of a future generation of Japanese that shall be of superior physique. The result from this and allied causes is already assured.

The training of the Japanese Bushi was, as we have seen, designed to produce men characterized not only by physical prowess but even more by a certain spirit. That spirit, finding individual embodiment, was Yamato Damashii, the Spirit of Japan. Of that spirit perhaps the most characterizing attribute was chugi, loyalty. Filial obedience and loyalty to one's superior are the fundamental virtues emphasized in Confucian thought. Of these China placed filial obedience first, while Japan has considered them essentially identical and given preference to that form of duty expressed by the term 'loyalty.’ There could be no real conflict between these two obligations when the ultimate superior was also the head of the great parental stock ; but whenever conflict appeared to rise, loyalty to one's leader justified the setting aside of every minor family claim. This obligation attained the force of an instinctive impulse. This loyalty may be criticised in that it seems always to have been to an individual rather than to a principle; but the question also may be raised as to what is law or principle apart from a personal law-giver, a will in conformity to which is the essence of loyalty.

Obligation is an interpersonal bond; and in the character of chugi, loyalty, we find that which, if more primitive, is also more nearly ultimate, the sense of utter obligation to a superior who is more than an abstraction of right or a formulation of principles. This loyalty to one's immediate lord, and ultimately to the Emperor, was fostered through the feudal ages by the sternest discipline. "Are you ready to die for your master?" was no unusual demand, even to children, and expected but one answer, unhesitatingly given, "I am ready."

Practice falls far short of the ideal theory in every sphere of human endeavor; yet upon the theory exemplified in the practice of the best the truest judgment is based. Both Japanese and European writers have doubtless idealized; but if, of the former, some seem clearly to have read the history and precepts of samurai training with eyes that beheld an after-image of Christian virtues, no less have romanticists and poets shed a halo over the life of Western chivalry. Little harm can be done by an over-appreciation; and certainly to the Bushido spirit of the samurai, of simple virtues and brutal passions often in strange contrast, Japan owes much of that character which to-day, as in the past, defies complete analysis because it is a living soul.

With the passing of feudalism, passed also the distinct status of the samurai. The Restoration proclaimed the equality of the four ancient classes: the soldier, the farmer, the artizan, the merchant; and perhaps nothing in all the history of Japanese military aristocracy gave more conclusive evidence to the character of that nobility than the spirit with which they laid down at the feet of the Emperor, privilege and property held for centuries. With the passing of the feudal order, the loyalty which had bound the samurai to individual leaders, centered upon one object, the Emperor, as supreme, a person and yet the embodiment of a great national ideal, who "represents to-day to each one of his fifty millions of subjects the unity, interests and glory of the whole." And while New Japan is increasingly a land of the common people, who are developing with remarkable efficiency, the families of old samurai-training and tradition have, in every walk of their unaccustomed life, displayed the spirit of their ancient education. The samurai to-day, for he exists in most respects unnoticed among his fellows, though he may draw the kuruma in which you ride about the streets, is conspicuous in this, he is still a gentleman ; and his wife or daughter, though perchance she cook your daily food, is a lady from whose gentle courtesy of manner many a lesson might be humbly learned.

Lombard, Frank Alanson. Pre-Meiji education in Japan; a study of Japanese education previous to the restoration of 1868. Kyo Bun Kwan, 1913.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.