[Note: This story contains potentially upsetting accounts of massacres and life as a refugee.]

This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Martyred Armenia and the Story of My Life by Krikor Gayjikian, 1920.

In a small town in eastern Turkey girt round with rugged mountains lies a small bungalow of one story in which I was born.

The town was made up of about two hundred of these houses, besides many barns and stables.

On the sides of the hills the shepherds tended their flocks of sheep and goats. In the outskirts of the town grazed the cattle. In the spring of the year the shepherds all lived in tents on the sides of the mountains, and they and their families lived on the milk of the sheep, goats and buffalo and what little wheat, corn, barley, beans, potatoes and tomatoes that they could raise. In the winter all moved down into the town, leaving several shepherds to care for the flocks.

Oxen and buffaloes were used for threshing wheat, drawing wagons and plowing the fields.

One evening in the autumn of 1895, just before the sun went down, when everyone was busy about his regular work and completing the tiresome duties of the day, a dark cloud of dust was seen rapidly approaching from, the south. The people finally discovered that the cloud of dust was made by a body of Turkish soldiers.

The town was in confusion. People were running hither and thither gathering up their scanty belongings and starting for the hills.

There were five members of my family, including myself. We took all we could carry of our household goods and started for the mountains with the rest of the townspeople. After walking all evening we became tired and stopped for the night. The next morning we were awakened by the cries of the children, who were cold and hungry, and were in need of shoes and clothing. The snow was falling faster and faster.

We looked back toward the town and beheld a sight that struck terror to our hearts. The Turks had set the town on fire and were shooting those who were unable to escape the night before, and those who had been so tired from their work that they were unable to keep up with the others who escaped. Children, women and men, both young and old, were mercilessly slain in cold blood. Those who had not gone far enough from their enemies were seized in their slumberings upon the ground and killed.

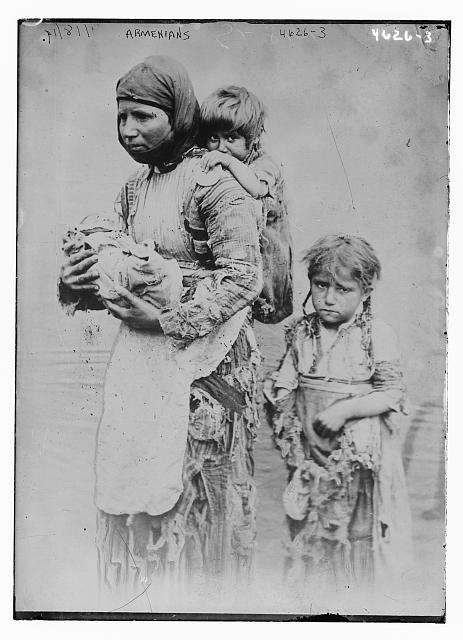

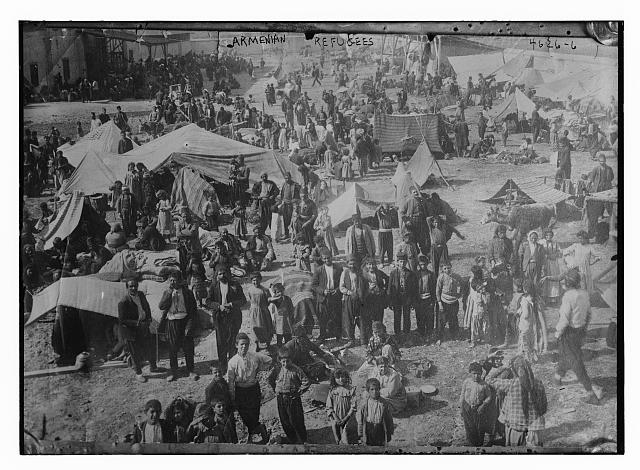

With heavy hearts we walked through the snow and cold to a town thirty miles distant, called Furnez. Here we rested for a few days, purchased a horse and left for Zeitun, the little children riding on the horse. Upon arriving at this city we found that there were people there from about twenty-five or thirty towns, who had been driven from their homes by Turkish soldiers. We lived for a while on the outskirts of the city and beheld day after day Armenian refugees coming into the city with all their belongings on their backs, and weeping and wailing for their loved ones who had been killed by the Turks.

I begged bread from day to day, and in that way kept our bodies and souls together until we were compelled to move into the city, because the Turks were surrounding it and our quarters were becoming more and more unsafe. The churches, school houses and all the public buildings were crowded with refugees, but we finally obtained shelter in an old abandoned cellar, where there were already five or six families.

This cellar was dark, damp and dungeon-like, with no windows, no door, and no floor. We slept on the ground with hardly enough covering to keep ourselves warm. For three months we had only dough to eat, made of corn meal mixed with a little butter, no water to wash in, no clothes to change. All three of us children became sick, having contracted colds and fever. My brother and sister died and all hopes of my recovery were vanishing, but mother was determined that I should live.

Mother being of the Greek Catholic faith, told the Lord that she would offer to Him a sacrifice of one goat if He would heal my body from these terrible diseases or plagues. Shortly after the Lord undertook and raised me up from my bed of affliction.

About this time the suffering in the city was terrible. Women went about fasting and praying for deliverance from the Turks, while the men who were yet quite strong, fought the enemy with a fixed determination to overcome.

Outside the city the Turks were suffering fiercely from the cold and lack of food. Many were taken sick and died.

When peace was declared, the rejoicing was great. Missionaries came to the city bringing us clothes, food and money. One of the missionaries came into the city accompanied by a colored man with a great pack on his back. This was the first colored man I had ever seen, and I was very much frightened at first, as everyone thought that he was a Turk; but when he opened his pack and began going from house to house, giving every member of every house a silver Turkish dollar, the rejoicing was beyond description.

During the war ninety thousand Armenians had been killed by the Turks, but God in His infinite mercy saw fit to spare my life, and the lives of my father and mother.

For two or three days we lived on the outskirts of the town again, living on greens, which we picked and cooked, and then decided to go back to our homes and try to rebuild the spot that remained dear in our memories.

We were about three days in traveling from Zeitun to the place where our beloved Gaban once stood, and when we arrived found nothing but charred ruins all around. Locating with little difficulty the place where our house had once stood, we dug in the ashes and found some flour which had been burned black. However, we took this black flour and made it into bread.

In a few days some missionaries came and furnished us with clothes and money enough to keep us from being naked and starving to death.

All of the people cleared away the ashes and ruins and began to rebuild. Trees were cut and the work started. The houses were built of stone with two rooms. The roof was made of wooden beams, covered with earth. The two rooms were divided into halves. One-half of one room was occupied by the donkey and ox; the other half was filled with hay. The goats occupied the other half room with the family. The family ate, lived and slept on the floor in their part of the structure.

At mealtime all gathered around the large bowl which was put in the middle of the floor, filled with food. Each one squatted on the ground floor and ate out of the bowl with his hands, unless there was soup, then wooden spoons were used. If there was not enough spoons, one waited until the other had finished and then took his turn eating. It was one mile to the nearest spring, where water could be procured for use both for washing and cooking purposes. Every other week water was carried from the spring to wash clothes. We took a bath about four or five times a year.

Early in the morning I would go up into the hills and cut wood, then carry it home on my back, with a supply of leaves for the goats. This was quite an enjoyable occupation in the summer time, but in the winter my feet suffered severely from the cold, they being protected by only a thin moccasin made of buffalo skin, tied on with a piece of string.

By this time the missionaries who had come into the town shortly after the war, had established schools and churches in the town. I attended the school for several years and one day went to the church. The singing and music attracted my attention, and I continued to go Sunday after Sunday. The missionary gave me a New Testament printed in the Armenian language, and I loved to read about Jesus, the story of His life and how He died on the cross for my sins. Upon professing to love Jesus and believing on Him, I was taken into the church.

Shortly after this my father went to the church and heard the missionary preach a sermon on becoming like little children in order to get into the kingdom of heaven. He became so troubled over this sermon on account of not being able to understand how he could become a little child again, that he lost his mind and in a short while died.

I remember one day after my father died, that I got an egg. This was such a luxury that I divided the egg in half and ate half at one meal, with two pans of bread, and the other half at the next meal with two more pans of bread. My mother was kept very busy patching up my clothes; they had so many patches on them it was a difficult job to find the clothes.

One winter morning we awoke to find everything dark, and upon going to the door to see what was the matter, found that it had been snowing during the night and the wind had blown the snow up against our house, completely covering it up.

Mother taught me the Lord's Prayer and another prayer which was, 'Lord supply our needs like you are supplying the blind wolf's needs." One day she explained this little prayer to me and this is how it is: There was once a shepherd who was constantly losing sheep from his flock. One day he determined to find out the reason for the disappearance of these sheep, and discovered that when he started to drive the sheep home, that one of them turned around and went in the opposite direction. Immediately he left the flock and followed the straying sheep. Over hills and through valleys he trudged until at last the sheep entered a cave. There, in the cave, was a blind wolf. The Lord had been sending these sheep to the cave to supply the needs of the blind wolf.

At this time meat was very cheap, selling at two or three cents a pound; but we were unable to buy it, as we were very poor. I went over to the spring and set traps to catch birds.

One day when I was out with the traps, a boy came and told me that my mother wanted me. Immediately he said that, I felt a sensation go through me that I had never felt before — neither could I describe it. I realized that something serious must have happened. When I asked him if she was dead, he told me a lie, and said that she was not, but just wanted to see me. I cried all the way home. When I arrived, there was mother cold in death. My only and best friend that I ever had in the world could answer my calls no more. My heart was broken, and it was a long time before I recovered from the shock.

Having lost my mother, father, brother and sister, I was now alone in the world, with no one to love me or take care of me. I decided to go to a city which was four days' walk from where I was. The name of this city was Adana.

When I arrived in Adana I was offered a job plowing from sunrise to sunset, at a rate of eighteen dollars for seven months. I worked at this job for about three weeks, and then left and went into the city. From then on I worked on the streets of the city, selling candy and doing odd jobs for a living. An old inn afforded me shelter during the nights. There were anywhere from five to ten roommates with me every night, and we all slept on the floor, pestered continually by many busy vermin. Many times I was bothered while sitting in church by these little annoyers.

One day as I was walking along the street, I saw some people going into a show, and I decided that I would go in, too, as I had never been in a show in my life. I went in and as a result, had to do without many comforts and buy cheap clothes.

While in Adana I noticed the people were beginning to seclude themselves; the stores were closed, and there were very few people on the streets, and soon war broke out in this place. There were more Turkish people in this city than Armenians. In a few days after we were told that the war was over and peace was declared. The Turks took all the arms from the Armenians, and then they started the war again, leaving us in a predicament.

I went to a church, then to a missionary home, but a fire broke out next door at night, and I was afraid and went out down through a dark alley, walked around and found another place, and tried to find shelter behind a wall around the church. During the night the houses of the Armenians around where I was were fired, and many people were burned up. Many were trying to find shelter inside the walls in the place where I was. Many were killed by the Turks in this raid. People had no place to sit down, nor food to eat, nor water to drink. It was a terrible wail that went up from that crowd. It was a hard thing to tell which were the rich people and which were the poor — all had been reduced to the same level.

When morning came, one stranger on horse-back came and took the people away in crowds to a place resembling our parks, and put them inside a wall. While here there was a message sent to the Turkish government, telling how many of the people were left, and demanding instructions as to the disposition of them. The message came back that we were to be set at liberty. The suffering had been so great during this period of the war that many thousands of the children died. I had but one dollar in my pocket, and went to selling buttermilk. This was the second time that the Lord spared me from the hands of the cruel Turk.

Gayjikian, Krikor. Martyred Armenia and the Story of My Life. God’s Revivalist Press, 1920.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.