Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

“My Home and My Family” from When I Was a Boy in Armenia, by Manoog Der Alexanian, 1926.

I come from a family of merchants and clergymen, my father having been a well-known merchant in my native city. He was a brave man, tall, well-built, of fair skin, brown eyes, and blond hair.

The house in which we lived in Adana was very modest in structure and appearance. It was built of sun-baked mud bricks. There were four buildings, each two stories in height, and facing each other, with a large courtyard in the center. Our house was flat-roofed; all Armenian houses are built in this fashion, to serve a special purpose. In the summer when the weather was too warm, we used to put up a screened chardack on the flat roof of our house and sleep upon it. This is an elevated wooden stand (like the band-stands you see in America) which can be easily dismantled and stored away for the winter.

As a boy I remember, when I was sent to bed early (all the Armenian boys go to bed early) during the summer evenings, how I used to lie on my back in bed on the chardack, watching the bright stars twinkling in the clear, blue sky; intently observing the milky way, and closely following the path of the shooting stars; for, according to an Armenian legend, each time a shooting star falls, a person dies in the direction pointed out by the meteor. How diligently I used to count those stars, until, tired of my boyish efforts to find an end, I fell asleep! It was a very pleasant way, indeed, to fall asleep.

In our courtyard we had a garden, a well, from which we got our drinking water, and a tonir to bake our bread. A tonir is a big earthen jar built on the ground, four feet in height, circular in shape, and with a round opening on top. When bread is to be baked, a fire is made inside the tonir. The dough, after being flattened on the board by an okhlavoo, is taken by the baker-woman on the palm of the hand and arm, and stuck to the inside hot walls of the tonir. In three minutes the bread is baked! This kind of baking makes the bread easily digestible, and it can be kept for a long time without moulding. After being baked, the bread is stored away in large wooden boxes. When it is to be used, it is sprinkled over with water and wrapped in a white cloth, or it may be eaten dry, like crackers. I preferred to eat mine dry, and found it was very tasteful. The bread-baking is done by professional baker-women who travel from house to house and ask if their services are needed. They usually know when bread is needed in such and such a family.

Our well had around its mouth a stone wall, about three feet in height, a wheel, rope, and pail. Each time we wanted water, we used to lower the pail into the well and draw out the water by the wheel.

I remember that it is very easy to fall into such wells and get drowned; many boys have been drowned in this way.

Our house was entered through a large door with two wings, an iron knocker on each wing. As we had no electric buttons, the visitor had to make use of this device in order to enter. When some one knocked at the door, I used to call out, “Who is there?” The visitor had to give his name in a loud voice, and only when we recognized a friend, did we open the door. Three families (all relatives) lived in our house, each occupying a two-story building.

The first story of our house was used for a cellar, where we kept twelve large earthen jars of provisions, filled with dried vegetables, fruits, cereals, raisins, nuts; and two large jars of wine. The cellar was my favorite; here I used to break in often and fill my pockets with raisins and nuts, of which I was very fond.

On the second floor we had one large and one small room spanned by a piazza. The former served as a kitchen and the latter as a living-room and dining-room. The third room was our sleeping chamber, where we had a yukluk covered with a curtain. A yukluk is a wooden, elevated structure, set inside the back wall, where our beds were kept in the daytime. We did not use any bedsteads (this is the custom with all Armenians). At bedtime, the beds are spread on the floor of the room, and in the morning they are folded and placed in the yukluk, and the curtain pulled over so that no one is able to see them. It is rather a back-breaking job for the women who have to fold the beds twice a day.

In the center of our living-room was a large rug, with long rugs on each side of the room, and cushions stuffed with wool. We had no chairs; we sat on these rugs, our legs folded, and leaned against the cushions. There were no pictures on the walls; instead we had twelve large bunches of winter grapes and six large winter melons hanging by ropes from the ceiling. And in place of electricity or gas, our room was lighted with three kerosene lamps. For ventilation, the door, windows, and fireplace served the purpose. Neither did we have steam heat or hot air; our room was heated with three manghals (tin receptacles held on tripods) in which we made a charcoal fire, and these, when ready, we brought into the room. The family then circled around to warm themselves. Another way of heating was the ojach, a kind of old-fashioned fireplace, where we made a fire. Altogether, we were quite warm and comfortable.

There were no “movies” or theatres in my home town. Usually the neighbors came to our house in the evening and told stories (hekiat), to which I listened with great attention and enthusiasm; or they would read the daily papers and discuss the news. Playing cards—particularly backgammon—(a favorite indoor sport with John Locke, the great English philosopher) is a very popular pastime in Armenia. Just as “bridge” is absorbing to Americans, so is the backgammon the delight of Armenians; once they begin, it becomes difficult for them to quit.

No Armenian boy or girl is allowed outside the house after six o’clock, unless accompanied by a chaperon. After I did all my studies, I went early to bed with a prayer; each morning, also, I prayed before breakfast.

The Armenian Food

Our food is simple but very wholesome. For breakfast we had fried eggs, tea, and bread. Lunch was light, but our supper rather elaborate.

Our food consisted of fresh, cooked vegetables, eggs, fresh lamb, and fresh fish. We are not acquainted with canned food, storage eggs, or storage meat. Everything we eat is bought fresh every day. We dried our vegetables for the winter.

The most favorite Armenian dishes in my town were pilav, madzoon, kufteh, sarma, dolma, and kebab.

Pilav is made of coarsely ground whole wheat after it is washed, boiled, and dried. Then it is cooked with tomatoes and fresh butter. This dish is very delicious and easy to digest.

Madzoon is what the Americans call “sour milk.” It is made by boiling the milk and letting it cool until it is lukewarm, then adding vegetable yeast, covering it, and letting ferment. In three hours’ time, you have delicious madzoon ready.

Many Americans who are surprised at the longevity of Armenians, may wish to know the cause; it is attributable partly to their sobriety and regular hours, but more especially to the use of madzoon. It has been well demonstrated by the great Russian bacteriologist, Metchnikoff, that madzoon or “sour milk” is a great aid to longevity by its helpful action on the bacteria in the intestinal tract.

Sarma and dolma are made by stuffing fresh minced-meat mixed with rice or bulgoor in grape-vine leaves, peppers, tomatoes, cucumbers, and cabbage. Kebab is broiled lamb.

The Armenian Family

Armenians observe an improved form of the old patriarchal family. The father or eldest living male rules supreme. The mother, on the other hand, is the queen of the house; she rules supreme in domestic affairs. Her duty is to see that the children are properly clothed, and look neat and clean. She does not mind her husband’s business, nor does the husband mix in his wife’s domestic affairs; there is a distinct division of work and duties between husband and wife. Each tries to excel in his own field. This system eliminates many unpleasant quarrels and misunderstandings, replacing them with mutual understanding, love, and devotion. In the evening the husband comes directly home from work; he has no clubs to go to, or business engagements to make, hence stays at home and passes his evenings pleasantly with his family.

Husband and wife are mutual companions in life, their aim being the upkeep and maintenance of a happy family.

There is mutual love and respect for each other; a sincere loyalty runs through the whole family. Every boy is envious of his family’s name and pride, and he will safeguard it zealously.

The father is considered the “king,” and the mother the “queen” of the house. Both are respected and implicitly obeyed by their children, who do not and cannot give them “back talk,” or tell them that they are wrong in this or that matter; they never say, “I won’t.”

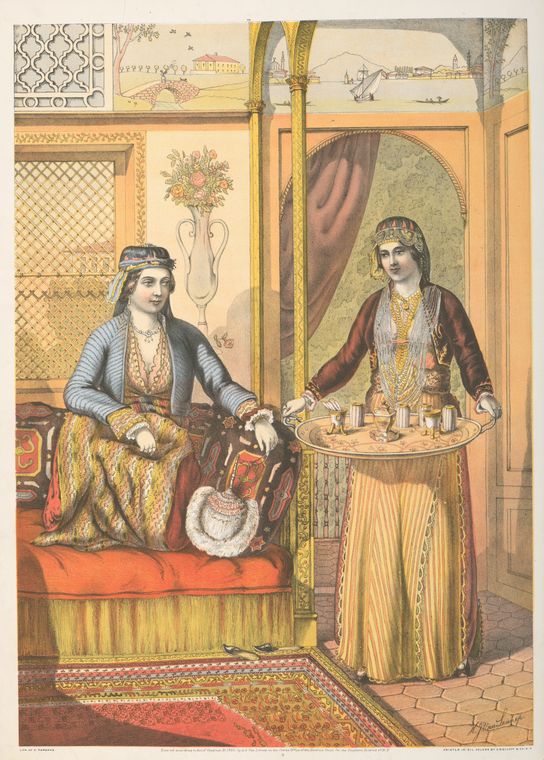

In the house, the father occupies the highest seat and is followed by his children according to their age. The young man cannot smoke in the presence of his parents, and is not allowed to talk without permission, especially in the presence of a guest. The daughters are the helpmates of the mother. Usually they serve their parents the coffee and refreshments, carrying the tray to the eldest member first and making a bow. After all cups are removed, they walk back and stand in the rear of the room, tray in hand, until all the coffee cups are emptied; then another bow as each person is approached and relieved of the china.

Grown-up boys and young men, even after they are married and have children of their own, refrain from smoking or drinking in the presence of their parents. Usually the married son does not leave his father’s house; it is a common thing to see an Armenian family with as many as sixty members. In our family there were twenty-two, all living in separate flats in the same house.

At meal times, the women do not join their men. Two separate dining-tables are set; one for the men, and another for the women and children. No woman joins the men’s table except the grandmother; it is not considered etiquette. Our dining-table was a large, round affair about one foot in height. We sat around this table, the eldest always sitting at the head. A prayer was said before and after each meal, usually by the youngest boy of the family. Before the meal, I used to repeat the Lord’s Prayer, and after the meal the following prayer: “May our God, the Father, bless and preserve the plentifulness of our table; blessed be His name; Amen.”

After dinner and a wash, men sit in the room and smoke their water-pipes (nargileh) or roll their cigarettes. I have often carried fire for the water-pipe; its gurgle and bubble amused me very much. After dinner we washed our hands under a faucet. When we had a guest, we had quite a different method of washing the hands, to wit: a round basin with a cover (punctured by many holes) on which there was an elevated place for the soap. Besides this we had an ubruk, a silver-plated metal jug filled with water. I used to sling a towel over my left arm, take the jug in my right, and, holding the washbasin in my left, make the round by setting the basin in front of the person who wished to use it, pouring water over his hands and handing him the towel.

Women begin to eat after the men are through. After the women are through eating, all dishes are washed and nothing is left unclean for tomorrow. There is no fight over “Who will do the dishes?” Nor is the husband asked “ to help his wife in the kitchen.”

In Adana, we had thirty mules and five horses kept in the stable in a khan (inn) of the city. We had a government contract for “the snow of the mountains.” Our mules were sent to the mountains with caretakers, who brought large blocks of snow wrapped in felt. When the snow reached the city, it was unwrapped and stored away in the straw pile in a one-story house. All the jobbers of the city had to come and buy the snow from us. As I mentioned before, Adana is quite warm in the summer, so we had much need for snow. It was mixed with different drinks and sold to the people by the jobbers. Each year we had to pay the government 250 Turkish pounds (a little over $1,000) for this privilege.

Besides the snow business, my relatives had three department stores for dry-goods. They were well-known for their honesty in business and charity to the poor.

Alexanian, Manoog Der. When I Was a Boy in Armenia. Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.