“It was extremely difficult to prevent a relapse into heathenism, seeing that to retain a converted community in the true faith, well-instructed ecclesiastics were indispensable, and these were few in number, the clergy being but too frequently persons of profane and ungodly life. In many cases it was doubtful whether they had even received ordination. Instances might therefore occur like that recorded in the Life of St. Gall, that in an oratory dedicated to St. Aurelia idols were afterwards worshiped with offerings; and we have seen that the Franks, after their conversion, in an irruption into Italy, still sacrificed human victims. Even when the missionaries believed their work sure, the return of the season, in which the joyous heathen festivals occurred, might in a moment call to remembrance the scarcely repressed idolatry; an interesting instance of which, from the twelfth century, we shall see presently. The priests, whose duty it was to retain the people in their Christianity, permitted themselves to sacrifice to the heathen gods, if, at the same time, they could perform the rite of baptism. They were addicted to magic and soothsaying, and were so infatuated with heathenism that they erected crosses on hills and with great approbation of the people celebrated Christian worship on heathen offering-places.

But the clergy were under the necessity of suffering much heathenism to remain if they would not totally disturb and subvert the social order of life. Heathen institutions of a political nature might no more be attacked than others which a significant and beneficial custom had made venerable and inviolable. The heathen usages connected with legal transactions must for the most part remain if the clergy would not also subvert the law itself, or supplant it by the Roman code, according to which they themselves lived. Hence the place and time of the judicial assemblies remained unchanged in their connection with the heathen offering-places and festivals; although the offerings which had formerly been associated with these meetings had altogether ceased. In like manner the old heathen ordeals maintained their ground, though in a Christian guise. Offenders must be punished, and the clergy patiently saw heathen practices accompanying the punishment, because the culprit was an unworthy Christian. In matters of warfare and the heathenism still practised in the field the clergy were equally powerless. Hence the Christian Franks, as we have already seen, when they invaded Italy sacrificed men while such cruelty in ordinary life had long been abolished among them. Thus did much heathenism find its way back during the first Christian age, or maintained its ground still longer, because it was sanctioned by law and usage. Where the converters in their blind zeal would make inroads into the social relations, the admission of Christianity met with many hindrances. The teaching of St. Kilian had found great favour with the Prankish duke Gozbert; but when he censured that prince for having espoused a relation, he paid for his presumption with his life. Among the Saxons Christianity encountered such strong opposition, because with its adoption was connected the loss of their old national constitution.

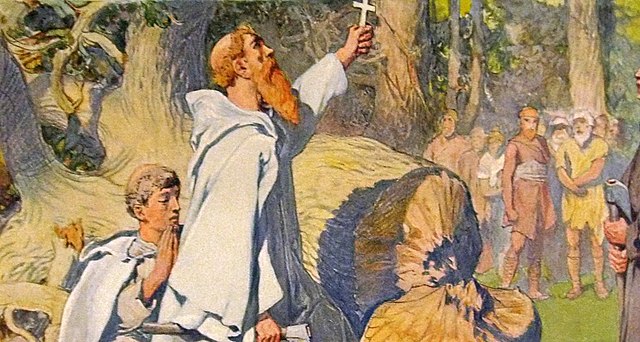

As the missionaries thus found themselves obliged to proceed with caution, and were unable to extirpate heathenism at one effort, they frequently accommodated themselves so far to the heathen ideas as to seek to give them a Christian turn. Many instances of such accommodations can be adduced. On places, for instance, regarded by the heathen as sacred. Christian churches were constructed, or, at least crosses there erected, that they might no longer be used for heathen worship and that the people might the more easily accustom themselves to regard them as holy in a Christian sense. The wood of the oak felled by Boniface was made into a pulpit and of the gold of the Langobardish snake altar-vessels were fabricated. Christian festivals were purposely appointed on days which had been kept as holy days by the heathens; or heathenish festivals with the retention of some of their usages were converted into Christian ones. If, on the one side, through such compromises, entrance was gained for Christianity, so on the other they hindered the rapid and complete extirpation of heathenism, and occafiioned a mixture of heathenish ideas and usages with Christian ones.

To these circumstances it may be ascribed that heathenism was never completely extirpated, that not only in the first centuries after the conversion, an extraordinary molding of heathenism and Christianity existed, but that even at the present day many traces of heathen notions and usages are to be found among the common people. As late as the twelfth century the clergy in Germany were still occupied in eradicating the remains of heathenism.

The missionaries saw in the heathen idols and in the adoration paid to them only a delusion of the devil, who, under their form had seduced men to his worship, and even believed that the images of the gods and the sacred trees were possessed by the evil one. Thus they did not regard the heathen deities as so many perfect non-entities, but ascribed to them a real existence, and, to a certain degree, stood themselves in awe of them. Hence their religion was represented to the heathens as a work of the devil, and the new converts were, in the first place, required to renounce him and his service. In this manner the idea naturally impressed itself on the minds of the people that these gods were only so many devils; and if any person, in the first period of Christianity, was brought to doubt the omnipotence of the God of the Christians, and relapsed into idolatry, the majority regarded such apostasy as a submission to the devil. Hence the numerous stories of compacts with the evil one, at which the individual who so devoted himself, must abjure his belief in God, Christ, and the Virgin Mary, precisely as the newly converted Christian renounced the devil. That the devil in such stories frequently stood in the place of a heathen god is evident from the circumstance, that offerings must be made to him in crossways, those ancient places of sacrifice.

But heathenism itself entertained the belief in certain beings hostile alike to gods and men, and at the same time possessed of extraordinary powers, on account of which their aid frequently appeared desirable. We shall presently see how in the Popular Tales the devil is often made to act the part which more genuine traditions assign to the giant race and how he not infrequently occupies the place of kind, beneficent spirits.

Let it not excite surprise that in the popular stories and popular belief, Christ and the saints are frequently set in the place of old mythologic beings. Many a tradition which in one place is related of a giant or the devil is in another told of Christ or Mary or of some saint. As formerly the minne (memory, remembrance, love) of the gods was drunk, so now a cup was emptied to the memory or love of Christ and the saints, as St. Johns minne, Gertrudes minne. And, as of old, in conjurations and various forms of spells, the heathen deities were invoked, so, after the conversion, Christ and the saints were called on. Several religious usages which were continued became in the popular creed attached to a feast-day or to a Christian saint, although they had formerly applied to a heathen divinity. In like manner old heathen myths passed over to Christian saints, some of which even in their later form sound heathenish enough, as that the soul, on the first night of its separation, comes to St. Gertrud. That in the period immediately following the conversion, the heathen worship of the dead was mingled with the Christian adoration of saints, we have already seen from the foregoing; and the manner in which Clovis venerated St. Martin, shows that he regarded him more as a heathen god than as a Christian saint. It will excite little or no surprise that the scarcely converted king of the Franks sent to the tomb of the saint, as to an oracle, to learn the issue of a war he had commenced against the Visigoths, as similar transmutations of heathen soothsaying and drawing of lots into apparently Christian ceremonies are to be found elsewhere.

We will now add two instances one of which will show how an individual mentioned in the New Testament has so passed into popular tradition as to completely occupy the place of a heathen goddess while the other will make it evident how heathen forms of worship can through various modifications gradually assume a Christian character.

Herodias is by Burchard of Worms compared with Diana. The women believed that they made long journeys with her on various animals during the hours of the night, obeyed her as a mistress and on certain nights were summoned to her service. According to Batherius bishop of Verona (ob. 974), it was believed that a third part of the world was delivered into her subjection. The author of Beinardus informs us that she loved John the Baptist but that her father, who disapproved of her love, caused the saint to be beheaded. The afflicted maiden had his head brought to bear but as she was covering it with tears and kisses it raised itself in the air and blew the damsel back so that from that time he hovers in the air. Only in the silent hours of night until cockcrowing does he rest and sits then on oaks and hazels. Her sole consolation is that under the name of Pharaildis, a third part of the world is in subjection to her.

That heathen religious usages gradually gave rise to Christian superstitions will appear from the following: It was a custom in tbe paganism both of Rome and Germany to carry the image or symbol of a divinity round the fields in order to render them fertile. At a later period the image of a saint or his symbol was borne about with the same object. Thus in the Albtbal according to popular belief, the carrying about of St. Magnus' staff drove away the field mice. In the Freiburg territory the same staff was employed to extirpate the caterpillars.

Sources:

"Northern Mythology: compromising the principal popular traditions and superstitions of Scandinavia, North Germany, and the Netherlands" -Thorpe Benjamin, London, E. Lumley (1851)

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.