“To the Germans no Edda has been transmitted nor has any writer of former times sought to collect the remains of German heathenism. On the contrary the early writers of Germany having in the Roman school been alienated from all reminiscences of their paternal country have striven, not to preserve, but to extirpate every trace of their ancient faith. Much, therefore, of the old German mythology being thus irretrievably lost, I turn to the sources which remain, and which consist partly in written documents, partly in the never-stationary stream of living traditions and customs. The first, although they may reach far back, yet appear fragmentary and lacerated, while the existing popular tradition hangs on threads which finally connect it with Antiquity. The principal sources of German mythology are, therefore, I. Popular narratives; II. Superstitions and ancient customs, in which traces of heathen myths, religious ideas and forms of worship are to be found.

Popular narratives branch into three classes :

I. Heroic Traditions (Heldensagen)

II. Popular Traditions (Volka- sagen)

III. Popular Tales (Marchen)

That they all in common -though traceable only in Christian times- have preserved much of heathenism, is confirmed by the circumstance, that in them many beings make their appearance who incontestably belong to heathenism, viz. those subordinate beings the dwarfs, water-sprites, etc., who are wanting in no religion which, like the German, has developed conceptions of personal divinities.

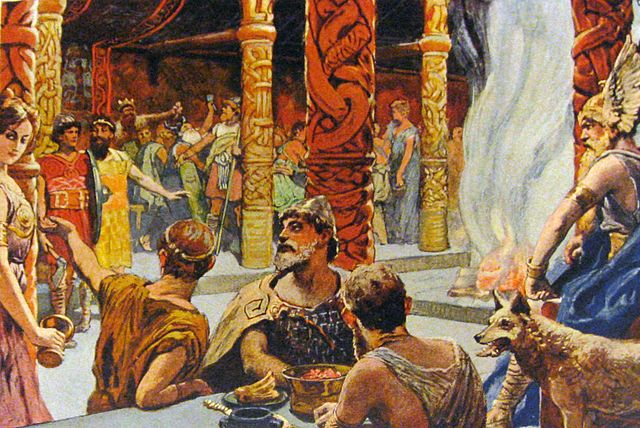

The principal sources of German Heroic Tradition are a series of poems, which have been transmitted from the eighth, tenth, but chiefly from the twelfth down to the fifteenth century. These poems are founded, as has been satisfactorily proved, on popular songs, collected, arranged and formed into one whole, for the most part by professed singers. The heroes, who constitute the chief personages in the narrative, were probably once gods or heroes, whose deep-rooted myths have been transmitted through Christian times in an altered and obscured form With the great German heroic tradition -the story of Siegfried and the Nibelunge, this assumption is the more surely founded as the story, even in heathen times, was spread abroad in Northern song.

If in the Heroic Traditions the mythic matter, particularly that which forms the pith of the narrative, is frequently concealed, in the ‘Popular Traditions’ (Volksagen) it is often more obvious. By the last mentioned title we designate those narratives which, in great number and remarkable mutual accordance, are spread over all Germany and which tell of rocks, mountains, lakes and other prominent objects. The collecting of those still preserved among the common people has, since the publication of the ‘Deutsche Sagen’ by the Brothers Grimm, made considerable progress. Of such narratives many, it is true, belong not to our province some being mere obscured historic reminiscences others owing their origin to etymological interpretations, or even to sculpture and earrings, which the people have endeavoured to explain in their own fashion; while others have demonstrably sprang up in Christian times, or are the fruits of literature. Nevertheless, a considerable number remain which descend from ancient times, and German mythology has still to hope for much emolument from the Popular Traditions since those with which we are already acquainted offer a plentiful harvest of mythic matter, without which our knowledge of German heathenism would be considerably more defective than it is.

The Popular Tale (Volksmarchen), which usually knows neither names of persons or places, nor times, contains, as far as our object is concerned, chiefly myths that have been rent from their original connection and exhibited in an altered fancifull form. Through lively imagination, through the mingling together of originally unconnected narratives, through adaptation to the various times in which they have been reproduced and to the several tastes of listening youth, through transmission from one people to another, the mythic elements of the Popular Tales are so disguised and distorted, that their chief substance is, as far as mythology is concerned, to us almost unintelligible.

But Popular Traditions and Popular Tales are, after all, for the most part, but dependent sources, which can derive any considerable value only by connection with more trustworthy narratives. A yet more dependent source is the Superstitions still to be found in the country among the great mass of the people, a considerable portion of which has, in my opinion, no connection with German mythology; although in recent times there is manifestly a disposition to regard every collection of popular superstitions notions and usages as a contribution to it.

Among the superstitions are to be reckoned the charms or spells and forms of adjuration which are to be uttered frequently, with particular ceremonies and usages, for the healing of a disease or the averting of a danger, and which are partly still preserved among the common people, and partly to be found in manuscripts*. They are for the most part in rhyme and rhythmical, and usually conclude with an invocation of God, Christ and the saints. Their beginning is frequently epic, the middle contains the potent words for the object of the spell. That many of these forms descend from heathen times is evident from the circumstance that downright heathen beings are invoked in them.

Another source is open to us in German Manners AND Customs. As every people is wont to adhere tenaciously to its old customs, even when their object is no longer known, so has many a custom been preserved, or only recently fallen into desuetude, the origin of which dates from the time of heathenism, although its connection therewith may either be forgotten or so mixed up with Christian ideas as to be hardly recognisable. This observation is particularly applicable to the popular diversions and processions, which take place at certain seasons in various parts of the country. These, though frequently falling on Christian festivals, yet stand in no necessary connection with them ; for which reason many may, no doubt, be regarded as remnants of pagan usages and festivals. And that such is actually the case appears evident from the circumstance, that some of these festivals, e.g. the kindling of fires, were at the time of the conversion forbidden as heathenish, and are also to be found in the heathenism of other nations. But we know not with what divinities these customs were connected, nor in whose honour these festivals were instituted. Of some only may the original object and probable signification be divined; but for the most part they can be considered only in their detached and incoherent state. It may also be added, that Slavish and Keltic customs may have got mingled with the German.

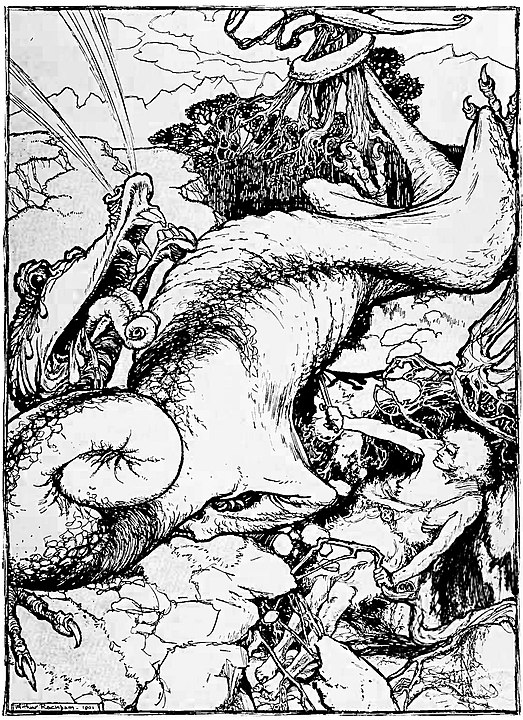

While the Scandinavian religion may, even as it has been transmitted to us, be regarded as a connected whole, the isolated fragments of German mythology can be considered only as the damaged ruins of a structure, for the restoration of which the plan is wholly wanting. But this plan we in great measure possess in the Northern Mythology, seeing that many of these German ruins are in perfect accordance with it. Hence we may confidently conclude that the German religion, had it been handed down to us in equal integrity with the Northern, would, on the whole, have exhibited the same system, and may, therefore, have recourse to the latter, as the only means left us of assigning a place to each of its isolated fragments…”

Sources:

“Northern Mythology: compromising the principal popular traditions and superstitions of Scandinavia, Germany, and the Netherlands” Thorpe Benjamin, London, E. Lumley (1851)

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.