Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

“Persian Rugs and Rug-Makers” from When I was a Boy in Persia by Youel Benjamin Mirza, 1920.

In Persia there are no ready-made toys for the girls to play with. They are, therefore, compelled to make their own rag babies. At a very early age little girls collect various colors and shades of cloth from which they make dolls.

They also take old stockings and unravel them and save the yarn, out of which they make balls to be used when they are playing on the housetops in the fall of the year. In playing the game the girls strike the ball to the ground with the palm of the hand and then make a quick turn. As it bounces it is given another blow so that the player can make another turn. This is kept up until the ball strikes a stone or a depression and gets beyond the control of the player, or else the girl, on account of making so many successive turns, falls from dizziness. I have witnessed from 180 to 200 turns being made without catching the ball or letting it fall. These balls are often beautifully ornamented with designs, tiny images of human beings, palm-leaves 'and birds.

The boys also play the game, but they are not so artistic as the girls, and neither do they have the patience to make the balls. So frequently a girl will present to a boy, either through his sister, her chum, or some confidential friend who will keep her secret, a beautiful ball which she has thus made out of yarn and ornamented. In this way the Persian girls have their first lesson in love, sewing, embroidery, and rug-making.

As soon as a girl reaches the age of understanding she is taught fancy weaving. The work of some of these young artists is beautiful. To teach them various designs the beginner is taken by the master of the art into the yard and the designs are drawn on the clay or sand. Sometimes they are drawn on paper, but paper being generally scarce the first means are invariably employed. When the pupil has mastered the drawing lessons she is shown the arrangement of every thread and the color that should be used. After accomplishing this the student must then make the designs in the rug or embroider them on a piece of cloth without looking at the drawing.

The Incentives to Becoming an Artist

The incentives to becoming an artist in the field of rug-making are indeed manifold. The first and foremost thought is to uphold the family name, the second, that it practically assures a young lady a good marriage, the third and final one, her artistic ability adds to her marriage dower at the final settlement of matrimonial arrangements between herself and her lover.

It is indeed not an unusual thing for a Persian beauty to put from seven to ten years into the making of a small rug as a gift for a prospective husband. Thus, being a work of love and a work of years, it is natural that, at its completion, it should not only shine like an Almas (diamond) but should fulfill all her dreams, hopes and fancies for a happy future.

The Material Used in Rug-Weaving

Wool, cotton, silk, goat's and camels hair are extensively used in the art of rug-making. The wool is obtained from shearing the sheep and the young Persian lambs. The lamb's wool, on account of its softness, is used in finer Persian rugs. The goats of Kurdistan and the Province of Azerbajin have long, fluffy hair with natural colors of black, white and brown. The hair obtained from these goats can not be surpassed in any part of the world with the exception of the Angora and the Cashmere of Tibet. The camel's hair is obtained mainly from the eastern part of Persia, as the camels of that locality have long, wooly hair.

All animals that produce rug material are sheared in the spring and fall. The sheep, goats, and Persian lambs after being fed in summer and winter come out of their pens fat and fluffy. They suddenly, however, change their appearance, and it is indeed a sight to see hundreds of these animals, after losing their woolen dress, running up and down the banks of a stream and trimmed all over with the exception of small tufts around the ears.

Cotton-raising is one of the most important industries in Persia. This material is used in rug-making on account of its several advantages. First, it is considered lighter than wool; second, it gives a better foundation on which to tie the pile; third, it keeps the rugs in better shape, and finally, the most important quality is that moths seldom get in rugs where cotton is used.

The famous Persian Abresem (silk) is obtained mainly from the regions bordering the Caspian Sea. In order to produce the silk great precaution is taken to assure the safety of the caterpillars from any danger of cold or noise. Primarily the silk-worms must be kept in a clean room with body temperature, and they must be guarded from all buzzing of flies and mosquitoes.

How the Material is Prepared

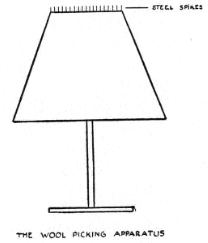

When the wool or other material for rug- making is thus obtained, it is put through a process of cleaning. The wool is first soaked in cold water and thoroughly washed until all its impurities have disappeared. It is then spread in the sun until it is well dried, but care is taken not to allow the wool to dry to the extent of losing its natural oil. After the wool has been cleaned it is put through a process of picking to loosen it so it can be spun into yarn. The apparatus for picking shown in the diagram is made of wood.

The top is full of steel spikes about an inch long. The instrument is placed firmly between the knees, and the wool is repeatedly pulled over the spikes until it is thoroughly mixed.

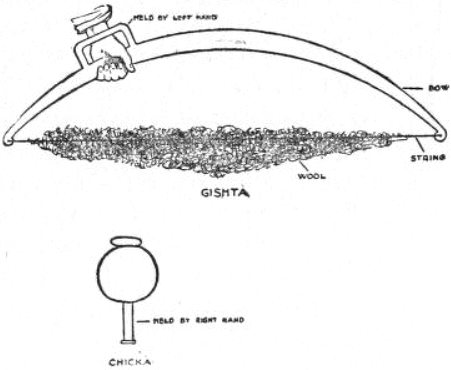

Another instrument used largely for picking is called by the natives, Gishta.

The use of this instrument is a trade and many men make a living by it. In the seasons of wool-shearing and cotton-picking, Gishta-users go from house to house to mix the wool or cotton so that it can be spun and finally used in making rugs and carpets. This instrument is shown in the diagram and consists of a bow made of wood, about six or seven feet long. The string of it is made of buffalo hide or some unbreakable material. The handle of the bow is held by the left hand, and the string, while touching the wool or cotton, is pounded with a wooden chicka (hammer) held by the right hand. As the string vibrates and springs up and down in the wool it mixes it and makes it ready for the next operation, spinning.

The looms and cotton-gins are so numerous in Persia that they can be found in almost every home. The spinning is done on the hand spinning-wheel by women, especially widows, who are compelled to make their living. The spinners work from four or five o'clock in the morning to the late hours of night, and if they spin during that time one pound of wool it is considered to be a good day's work.

When the wool is spun it is then wound up in large skeins and made ready for the dyers.

The Dyer and the Method of Dyeing

In Persia the dyers can be recognized a long distance off by the color of their hands. That they are dyers makes them not only exceedingly proud, but they feel quite happy over the fact that their hands show the marks of their profession. The craft is hereditary and it descends as sacred treasure from father to son for generations. The dyers are all men. In the case of a weaver not being able to make or prepare his own dyes, the yarn is taken to one of the dyers and dyed the desired color and shade.

Dyes are prepared from leaves, plants, roots, and the bark of trees, insects, animal blood, vegetables, and flowers. After the colors have been extracted they are put in big pots, boiled, and reboiled, until a satisfactory shade has been obtained. When the dye is ready to be used, the dyer takes one skein of yarn at a time and dips it into the dye until the desired tint has been obtained. It is then taken out and hung over the dye-pot in the sun without being wrung out.

The dyeing season is usually in the latter part of spring, or at times when the rains do not fall. In passing by the villages one can easily recognize the dyer's home: on his housetop and in the yard there will be seen skeins of yarn of various colors hung on ropes to dry. When there are several dyers in the same village the display of colors is truly picturesque and, to a stranger, it would seem that the village was having a big holiday, or that they were commemorating a great national event.

The dyers that I knew in Persia were the best-hearted men that I ever saw. The boys liked them more than anybody else in the village. We used their yards and housetops as loafing-places, and not in- frequently, to get us out of the way when they were working, they gave us colored yarns out of which we made our King David sling-shots.

The Loom and Weaving

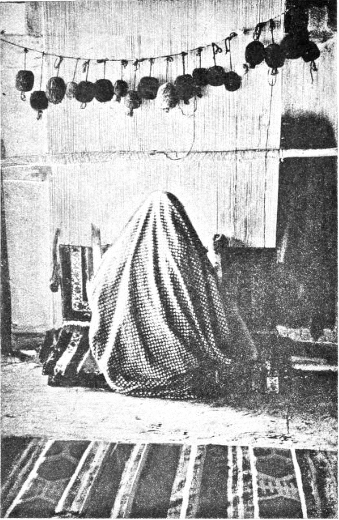

The apparatus used in weaving a Persian rug is indeed a very simple and not at all complicated piece of mechanism. The whole loom is made of four rough poles, two of them firmly set in the ground like telephone poles, another placed across these at the top and another at the bottom, thus forming a wooden frame. This is regulated according to the size of the rug. The warp threads are stretched from the top to the bottom pole, with a smooth stick inserted between the threads as a shuttle. When this is done the rug painting begins.

The Persian weaving, like Persian reading and writing, always begins at the right and goes to the left. The craft, on account of requiring small, dainty hands to tie the close knots and stitches, is performed mainly by the delicate fingers of women and girls.

The weavers are very superstitious. They would not think of commencing their work without first invoking the blessing of Allah by saying, "Bismil lah-el Rahemone el Rahum," meaning, "In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate." When the neighbors come to see their work they are given most wicked looks unless before making any complimentary remarks they say, "Mashallah, Mashallah.” Again, to avoid the evil eye of their neighbors or visitors they tie blue beads in the rug and leave the tufts of wool undipped, not keeping track of how much work they accomplish during the day, or the space they cover. Frequently, upon commencing their work next morning they look to see whether the devils or genii have interfered with their designs. They also believe that genii come at night and do their weaving for them and braid the fringes of their rugs.

One of the principal reasons that a Persian rug is so durable and lasting is the method of knotting. Every knot is made separately so that in case it should come out it would not affect other knots or rows in the rug.

How Long Does It Take To Make a Persian Rug?

The question of how long it takes to make a Persian rug has been asked frequently. For this reason I will give as an example how much time and labor it requires to make one of the standard American size. A 9 x 12 rug made in Persia by a fine weaver would have at least 400 handmade knots to the square inch, or 6,220,800 knots when completed. In tying the knots the weaver must exercise a great deal of skill and care, so it is very doubtful that even the fastest and most expert weavers can tie more than three knots per minute.

Therefore if a weaver works eight hours every day in the year it will take eleven years, ten months and five days to complete this piece of work.

How the Persian Rugs Are Named and Classified

The Persian rugs take the names of districts or cities in which they are made. For example, the Tabriz rug is called by that name because it is made in the city of Tabriz. The Teheran rug is made in the Persian capital city, the Sheraz rug in the city of Sheraz. Sometimes erroneously the rugs are named from the city in which they were sold or shipped, such as "Kirmanshah" rugs. There are thousands of Kirman rugs that are sold as "Kirmanshah" simply because that was the last place from which the rugs were purchased.

The rugs are also classified according to their weave and grade. The following are the most important rugs made in Persia and exported largely to England and the United States: Senna, Sorrook, Kirmanshah, Kashan, Tabriz, Kirman, Sheraz, Teheran or Irani, Khorassan, Saraband, Herat, Ferogan, Hamadan, Kurdistan, Ispahan and Sultanabad.

Until recent years very few weavers wove rugs with the idea of selling them. Rugs were made primarily for the use of the family. Occasionally, however, when a friend or stranger admired the precious article to the extent of causing the "evil eye" to come upon it and on the family that owned it, the rug was either given away or sold for a few pieces of silver. The rugs that we had were mainly bought or presented to my grandfather by Kurdish chieftains. Some of the rugs which we used in our house have not, as yet, to my knowledge, found a place in the American market.

These are large felt carpets called by the natives, "Lumta." They are made, not by weaving, but by beating the wool together and then pressing it. They are very thick, warm and noiseless, with red, cream, and white borders. The field of these carpets is frequently dotted with red, black, white, green, blue and golden circles of wool. Besides felt carpets there were also long, narrow rugs from 4 x 12 feet and upward. I once asked my father to tell me how much some of these rugs cost. The one 4 x 12 I was told cost originally about $2.40, and the largest ones that I saw never cost more than $18 in American money. I believe that, even now, the rugs can be bought at a very low price, but strangers or rug agents who are not acquainted with the character and customs of the Kurds and other fastidious rug-owners, would be subject to robbery and many great disappointments in purchasing these rugs from the homes of the owners.

Mirza, Youel Benjamin. When I Was a Boy in Persia. Lothrop, Lee, Shepard Co., 1920

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.