Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From When I Was a Boy in China by Yan Phou Lee, 1887.

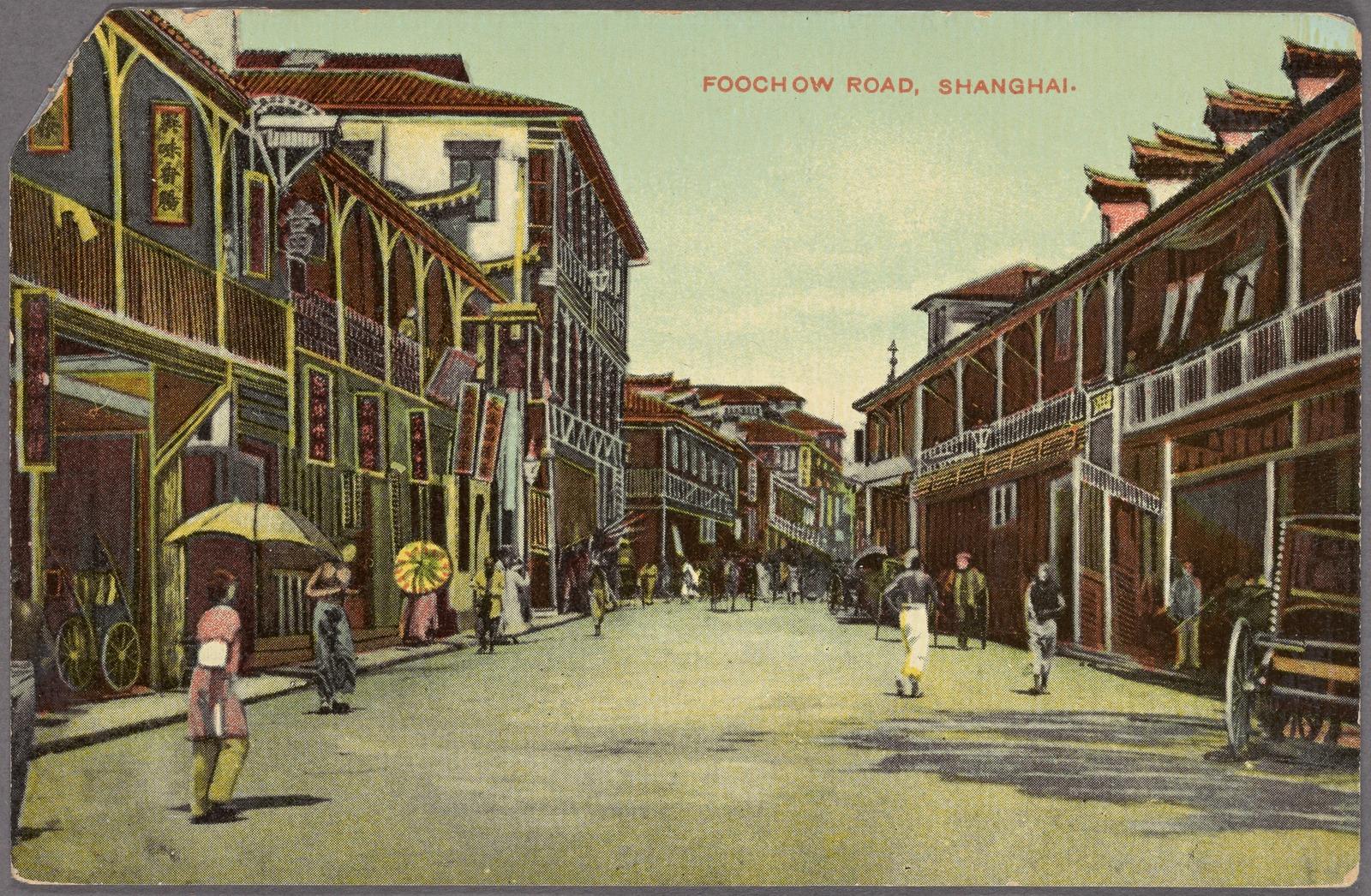

On our arrival at Shanghai, my cousin took me to see our aunt whose husband was a comprador in an American tea warehouse. A comprador is usually found in every foreign hong or firm. He acts as interpreter and also as agent for the company. He has a corps of accountants called shroffs, assistants and workmen under him.

My uncle was rich and lived in a fine house built after European models. It was there that I first came in immediate contact with Western civilization. But it was a long time before I got used to those red-headed and tight-jacketed foreigners. “How can they walk or run?” I asked myself curiously contemplating their close and confining garments. The dress of foreign ladies was still another mystery to me. They shocked my sense of propriety also, by walking arm-in-arm with the men. “How peculiar their voices are! how screechy! how sharp!” Such were some of the thoughts I had about those peculiar people.

A few days after, I was taken to the Tung Mim Kuen, or Government School, where I was destined to spend a whole year, preparatory to my American education. It was established by the government and was in charge of a commissioner, a deputy-commissioner, two teachers of Chinese, and two teachers of English. The building was quite spacious, consisting of two stories. The large schoolroom, library, dining-rooms and kitchen occupied the first floor. The offices, reception room and dormitories were overhead. The square tables of the teachers of Chinese were placed at each end of the schoolroom; between them were oblong tables and stools of the pupils.

I was brought into the presence of the commissioners and teachers; and having performed my kow-tow to each, a seat was assigned me among my mates, who scanned me with a good deal of curiosity. It was afternoon, and the Chinese lessons were being recited. So while they looked at me through the corners of their eyes, they were also attending to their lessons with as much vim and voice as they could command. Soon recitations were over, not without one or two pupils being sent back to their seats to study their tasks over again, a few blows being administered to stimulate the intellect and quicken memory.

At half-past four o’clock, school was out and the boys, to the number of forty, went forth to play. They ran around, chased each other and wasted their cash on fruits and confections. I soon made acquaintance with some of them, but I did not experience any of the hazing and bullying to which new pupils in American and English schools are subject. I found that there were two parties among the boys. I joined one of them and had many friendly encounters with the rival party. As in America, we had a great deal of generous emulation, and consequently much boasting of the prizes and honors won by the rival societies. Our chief amusements were sight-seeing, shuttle-cock-kicking and penny-guessing.

Supper came at six when we had rice, meats and vegetables. Our faces invariably were washed after supper in warm water. This is customary. Then the lamps were lighted; and when the teachers came down, full forty pairs of lungs were at work with lessons of next day. At eight o’clock, one of the teachers read and explained a long extract from Chinese history, which, let me assure you, is replete with interest. At nine o’clock we were sent to our beds. Nothing ever happened of special interest. I remember that we used to talk till pretty late, and that some of the nights that I spent there were not of the pleasantest kind - cause I was haunted by the fear of spirits.

After breakfast the following morning we assem- bled in the same schoolroom to study our English lessons. The teacher of this branch was a Chinese gentleman who learned his English at Hongkong. The first thing to be done with me was to teach me the alphabet. When the teacher grew tired he set some advanced pupils to teach me. The letters sounded rather funny, I must say. It took me two days to learn them. The letter R was the hardest one to pronounce, but I soon learned to give it, with a peculiar roll of the tongue even. We were taught to read and write English and managed by means of primers and phrase-books to pick up a limited knowledge of the language. A year thus passed in study and pastime. Sundays were given to us to spend as holidays.

It was in the month of May when we were examined in our English studies and the best thirty were selected to go to America, their proficiency in Chinese, their general deportment and their record also being taken into account.

There was great rejoicing among our friends and kindred. For the cadet’s gilt button and rank were conferred on us, which, like the first literary degree, was a step towards fortune, rank and influence. Large posters were posted up at the front doors of our homes, informing the world in gold characters of the great honor which had come to the family.

We paid visits of ceremony to the Tautai, chief officer of the department, and to the American consul-general, dressed in official robes and carried in fine carriages. By the first part of June, we were ready for the ocean journey. We bade our friends farewell with due solemnity, for the thought that on our return after fifteen years of study abroad half of them might be dead, made us rather serious. But the sadness of parting was soon over and homesickness and dreariness took its place, as the steamer steamed out of the river and our native country grew indistinct in the twilight.

Lee, Yan Phou. When I Was a Boy in China. D. Lothrop Company, 1887.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.