Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

“Boys and Girls at Home” from When I was a Boy in Palestine by Mousa Kaleel, 1914.

"That our sons may be as plants grown up in their youth;

That our daughters may be as corner-stones, polished after the similitude of a palace."

Psalms, cxliv: 12.

This is an old, old saying, but it still describes the ideal child of Palestine, The period of boyhood or girlhood is shorter in Palestine than in the United States, but often merry. Children are the rulers of most houses in the country villages. If they are well, they run in and out in all kinds of weather, barefooted and bareheaded. If they are not well, not over-much attention is paid to them at first, except to bring them dainties to eat. If the illness turns out to be genuine, however, all the medical help within reach is summoned, but if, as usually happens to be the case, dread of the schoolmaster's stick is at the bottom, they soon recover when their mothers take them to school and make matters all right with the teacher.

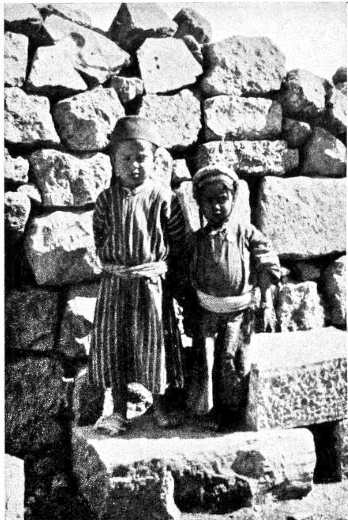

The poorer children are seldom bothered with more than one garment, except sometimes a skull-cap. If the parents can afford it, they provide a little cloth cap embroidered with colored silk and with a few bangles of blue beads sewed on the front. The beads serve the purpose of protecting the child against what is called the “Ayen,” or eye. The tradition is that God will take the choicest boys, especially if they are admired by onlookers, so the blue beads are provided to counteract any wicked looks the child may encounter. To protect the child against evil spirits, his guardians provide him with a small leather purse that has some texts from the Bible or the Koran, as the case may be, written on it. As the boy grows older, he may be given a jacket to wear over the little shirt. The girls have a little shawl to wrap around their shoulders and a row of coins on their head-dresses.

When very little, boys and girls play together in the streets and around the ovens, sometimes even on roofs. By the time they are six, however, they separate and play with their own kind and choose different games. The boys become wild in their play, while the girls begin to help around the home.

Here is an impression of the children in Palestine, given by an early traveller.

“From earliest infancy they are brought up in utter ignorance; they are never children; the merry laughter and sports of European childhood are here quite unknown. At three years they are little men and women with wonderful aplomb. Tiny tots scarcely able to toddle may be seen gathering khobbayzeh (wild mallows) for the evening meal, and, when they have filled the skirts of their one wee garment, will trot home as sedately as though the cares of life were already pressing heavily on their shoulders. I have seldom in this country heard a genuine laugh from man, woman, or child; the great struggle for existence seems to have crushed all but fictitious mirth.

“The fellaheen boys—very rarely the girls—take charge of the flocks and herds till they are old enough to consider themselves men; thus exposed to all weathers they are as hardy as their charge, but if one is attacked by sickness, one is as little cared for as the other, and chronic coughs, fevers, rheumatism, and ophthalmia are the consequent results."

Further on he concludes:

“The fellaheen (peasants) are all in all the worst type of humanity that I have come across in the East." Or in other words, the world.

I am almost tempted to charge the writer of the passage with writing for dramatic effect, but I will not. He may be sincere. A tourist who sees one child doing a certain thing concludes that all children in Palestine do likewise. It is not an uncommon thing, however, to find a whole family ruled by the whims of a little child, and loving fathers cannot stand against the crying of their children. So tender are they in their love that they often do even ridiculous things to please their children, such as letting them ride on their backs.

A traveller through Palestine may see a tiny girl helping her mother in her play by gathering greens, or a boy living with his father's flocks when they go up in the mountains for the summer. It is a case of preference and enjoyment rather than of slavish labor. As for the peasants being the worst people in the East, the writer of the passage may have had some personal experience with a band of brigands. Later on in his work he fears that his sketch “will seem over-colored," and cites, as an added proof of the depravity of the people, an incident of being abused in “the most scurrilous language" by the children!

Boys in Palestine, I must admit, are fighters, and are taught by their parents to fight. This is justified by the internal conditions of the country, caused by a very slack and weak government. The boy must grow into a man who has a good aim with his gun, and who can hurl a stone a great distance with accuracy. It is a semi-primitive land, and men have to live accordingly to get along in it. The people are good at heart and often blessed with the keenest brains in the world; all they need is some gentle leadership that will be willing to come down to their ranks, even below, if need be, and lift them up gradually.

It is natural that they should resent any “Khawaja” (an upper-class foreigner) trying to make a curiosity of them, continually shooting at them with clicking cameras, and asking insolent and prying questions about their sanctuaries. Many of the tourists who visit Palestine do so from a desire to study the religious customs of the people from a scientific point of view, and they thoughtlessly offend the people by apparently making light of what are very sacred things. The lowliest peasant in Palestine is vain, and the tiniest boy can throw a stone. With these as acknowledged facts let the missionary and investigator work.

The children spend wintry evenings listening to tales, usually by the grandmother, but sometimes by the mother.

The stories are mostly all like the “Arabian Nights." The success of the story does not always depend upon thrilling events, but a great deal upon the method of the story-teller. A well-told story is punctuated with wishes and exclamations. It is begun by wishing the well-being of the hearers and the home. When a death is related, the teller prays God to preserve her hearers from death, and when the hero attains happiness, she wishes happiness for her listeners. Often, to collect his thoughts, the story-teller begins a digression by saying, “May peace remain with you,'' continuing to gain time by adding other good things, “and health and strength and wealth," etc.

Thus are the happy evenings spent in winter around a great fireplace filled with crackling, oily olive logs. If it rains hard, and the wind blows fiercely, the children chant a little juvenile song, beginning thus:

"Umtree wazadee Baitna adeedee."

It is addressed to nature, and means,

"Rain and increase, our house is made of iron."

Those who do not farm usually say,

“Umtree ala ayn Khazzan kumheh,"

which means

“Rain to the spite of him who stores his grain (wheat)."

This is a sort of vindictive expression against the man who hoards his grain, anticipating a scarcity of rain, which is sure to cause higher prices. It shows that human nature is the same the world over, and that “corners'' in wheat are not anymore popular in Palestine than in the United States.

The following story is sometimes told to boys to check their foolhardiness and warn them against foolish pride, and to induce obedience to fathers:

A young tiger who had heard about the ability of men, though he had never seen a man, felt so eager in his strength to have a combat that he told his father he wanted to go out and find a man and have a fight with him. The father tiger, advising against such an undertaking, said:

“Even I, who am older and stronger than you, should not think of seeking a fight with a man, for I cannot prevail against him."

But the young, proud tiger, not heeding his father's advice, went to seek a man. He journeyed until he came to a road much frequented by travellers, and lay down under a tree to await the foe. While waiting there, he saw a camel running down the road, although loaded heavily. The camel was running away from his master. The young, inexperienced tiger got up, and said to the camel:

“Are you a man?”

“I am not a man, but am running away from one, because he loads such heavy burdens on me,” replied the camel.

The young tiger thought to himself: “How strong must the man be if he causes so much distress and fear in this great creature.”

Next passed a horse, and the tiger thought, “Maybe this is the man,'' but received a negative reply to his question as he had from the camel. Then came along a weak little donkey, loaded with wood and driven by a man. The tiger asked his question of the man:

“Are you a man?"

"Yes," the man answered.

Then the tiger said, “I have come to have a fight with you."

“All right," said the man, “but I am not quite ready now. May I tie you with my rope to the tree until I come back?”

The tiger allowed the man to tie him, which the man did very securely. Then he cut a strong, thick club from the tree, and began to beat the tiger with it.

“Oh, please let me go! " the tiger cried out in pain. “I'll never try to fight with a man again."

So the man let him go, and the young tiger went to his father and told his experience.

Kaleel, Mousa. When I was a Boy in Palestine. Lothrop, Lee, and Shepard Co. 1914.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.