Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From The Aztecs: Their History, Manners, and Customs by Lucien Biart, translated by John Leslie Garner, 1900.

The multiplicity of the Mexican gods required a great number of priests, who were almost as highly venerated as the divinities they served. When we remember that the great temple of Mexico sheltered at least five thousand, and that four hundred were engaged in the worship of Tezcatzoncatl, the Aztec Bacchus, we may believe the historians when they place the total number at a million. The honors that were paid the priests, the respect that was shown them, induced young men to enter the sacerdotal state. The nobles consecrated their children to the service of the gods for a stated time, and their example was followed by the lesser nobility, who accepted subordinate positions. To serve the gods was, among the Aztecs, to honor one's caste, and at the same time to acquire a sign of distinction.

The priests were separated from each other by several hierarchical degrees. The first of the supreme pontiffs—there were two of them—bore the title of Teoteuctli (“divine lord"), and the second that of Hueiteopixqui ("high-priest") These two dignities were conferred only on persons illustrious by birth, or on account of their probity, or their knowledge of the religious ceremonies.

The high-priests were oracles, whom the kings consulted at critical times, and war was never undertaken without their consent. It was they who consecrated kings, and who tore the heart from the human victims in the sacrifices. The high-priest of Mexico was the head of religion throughout the empire; but the nations conquered by the Aztecs, with a political genius not inferior to that of the Romans on this point, preserved their own worship.

The dignity of pontiff was conferred by election; but it is not known whether the electors were priests or the nobles charged with the election of the kings. In Mexico the badge of this dignity consisted of a tuft of cotton attached to the breast. During the feasts the emblems of the divinity that was being honored were worn on the luxurious vestments of the high-priest.

Next to the two priestly dignities just mentioned, the highest was that of Mexitliteohuatzin, which the high-priest conferred. The duty of this minister consisted in supervising the observance of the rites and the forms in religious feasts. At the same time he watched over the conduct of the priests placed at the head of seminaries, for the purpose of punishing those who neglected their duties. On account of his complicated functions he was assisted by two aids, or vicars, one of whom held the office of superior-general of seminaries. As a badge, the first of these vicars always carried a bag of incense on his person.

Next in the hierarchical order came the Tlatquimilolteuctli, or steward of the sanctuary; then the composer of hymns sung during the feasts, the Ometochtli. The ordinary priests were designated by the name of Teopixqui ("minister of God"), a term which to-day is applied to Catholic priests. In each quarter of Mexico a principal priest directed the feasts and religious acts.

Among the priests there were still others, called sacrificers, diviners, and chanters; of these last, some served during the day and others at night.

Next came those charged with cleaning the temple, ornamenting the altars, educating the young, regulating the calendar, and finally with the production of mythological paintings.

Four times a day—in the morning, at midday, in the evening, and at midnight—the priests were required to incense the altars. At this last hour the most important ministers of the temple came to assist the one that was keeping watch. They burned incense to the sun four times during the day, and five times during the night. The perfumes employed were liquid styrax (liquidambar styraciflua), and copal resin (rhus copallina).

At certain festivals they used chapopotli,—a sort of bitumen which was collected on the shore of the Gulf of Mexico, and which seems to come from submarine volcanoes. The censers were made of clay, or at times of gold, provided with a handle, and were similar in form to our saucepans. Every morning the priests painted their bodies black with soot, and on this they traced designs with yellow or red ochre. At evening they all bathed in pools within the enclosure of the temples.

The ordinary dress of the Aztec priests resembled that of the other citizens, with the exception of the black cotton cap which they wore. During the ceremonies they wore a sort of mantle. They allowed their hair to grow; sometimes it descended to their feet. They tied it up with ribbons, or left it unconfined and daubed it with colors, which gave them a hideous appearance.

Besides the paintings with ochre, they prepared others for the sacrifices that took place on mountain-tops or in dark grottos. Taking scorpions, spiders, worms, small vipers, and other repugnant or venomous animals, they burned them on the hearths of the temple; then they mixed the ashes with water, soot, tobacco, and living insects. Having presented this mixture to the gods, they smeared their bodies with it. Thus covered they faced all dangers, persuaded that they had become invulnerable, and that they could brave the teeth of wild beasts and the mouths of serpents.

This mixture, which was called Teopatli ("divine medicine"), was regarded as a remedy for all diseases. The pupils of the seminaries were charged with collecting the animals required for the manufacture of this strange ointment, which is still in use among the Indians. The teopatli was also used in enchantments, and in the popular mind it has preserved its supernatural virtues up to the present time.

The Mexican priests led an austere life and fasted frequently. They rarely drank fermented liquors, and never became intoxicated. The three hundred and three ministers of Tezcatzoncatl, having ended the song by which they invoked him, placed three hundred and three reeds in the immense jar which was always kept full of agave wine by his devotees, set before the altar; one alone of these reeds was hollow. The priest to whom the hollow reed fell by lot had a right to drink the fermented liquor, since he alone could suck it up.

During the days when duty kept them in the temple, the priests avoided meeting all women except their own wives; if they chanced to encounter a strange woman, they passed her with eyes downcast in order not to see her. All incontinence on the part of the priests was severely punished. At Teotihuacan, the priest convicted of having violated the laws of chastity was delivered to the people, and beaten to death with sticks at night. At Ichcatlan, the high-priest was required to live in the temple, and abstain from all communication with women. If, unfortunately, he failed to observe this rule, he was killed, and his limbs presented to his successor, as a warning.

If a priest did not get up to assist at the night services, his ears and lips were pierced, or his head sprinkled with boiling water. On a second offence, he was expelled from the temple, and during the feast of the god of waters, was drowned in a lake. Ordinarily the priests lived in a community, under the surveillance of a superior. The sacerdotal office among the Aztecs lasted only for a stated time, at the end of which the priests retired or returned again to civil life, to occupy important positions. However, some of them devoted themselves to the service of the gods for their entire lives. Women were admitted to the priesthood, but their offices were limited to incensing the idols, keeping up the sacred fire, sweeping the temple, preparing the provisions for offerings, and presenting them at the altar; they could neither sacrifice to the gods nor aspire to the higher dignities, no matter what their capacity.

Among these priestesses, some were consecrated to the religious life by their parents from their childhood, while others bound themselves voluntarily, by vows, for one or two years, either after a sickness, or to make a good marriage, or to interest the gods in the welfare of their families.

The consecration of the first was practised as follows: At the birth of the child the parents offered it to the divinity whom they worshipped, and advised the priest of their district of this act, who communicated it to the Tepanteohuatzin, or superior-general of seminaries. Two months afterwards they took the child to the temple and placed a passion-flower, a small censer, and a little incense in her hand, as symbols of her future occupations.

Every month this ceremony was repeated, and the barks of trees intended for the sacred fire figured in it. At five years the little girl was sent to the Tepanteohuatzin, who placed her in a seminary. There she was instructed in the rules of religion, she was taught how to conduct herself, and to busy herself with work suited to her sex. In regard to the young girls who entered a seminary in consequence of a vow, they first were required to sacrifice their hair.

They all lived greatly secluded, in quiet and meditation, under the surveillance of superiors. Some arose before midnight, others after, and still others before the break of day, to keep up the fire and incense the idols. Although priests assisted at the ceremony, they were not allowed to communicate with the priestesses.

Every morning these latter busied themselves in preparing the provisions for offerings, and in sweeping the aisles of the temple. When their regular duties were ended, they occupied themselves in spinning or weaving rich stuffs to clothe the idols and ornament the altars. The chastity of these vestals was the constant object of the surveillance of their superiors, and the least fault met with no pardon.

When the young girl, who had been consecrated to the worship of the gods since her childhood, reached her seventeenth year, her parents looked for a husband for her. When they had found one, they presented quails, incense, flowers and edibles on a handsome dish to the Tepanteohuatzin, thanking him for the care he had taken in the education of their daughter, and asking permission to give her in marriage. The high dignitary generally granted the request, and exhorted his pupil to a complete observance of the new duties she was about to take upon herself.

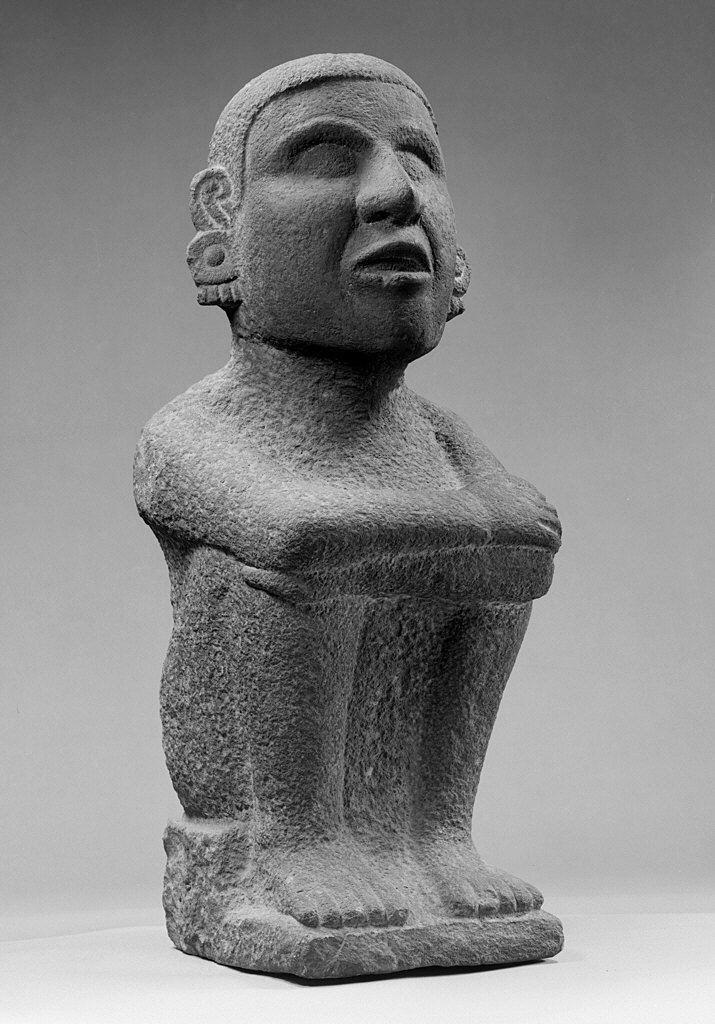

Kneeling Female Figure, 15th–early 16th century.

Among the different Mexican religious orders,—there were some for women, and some for men,—those who had Quetzacoatl for a patron deserve special mention. They followed a most severe life; they plunged into the water at midnight and watched almost until daylight, singing hymns or performing acts of penitence. These priests and priestesses had a right to betake themselves at all times to the forests, and to bleed themselves,—a privilege which they enjoyed by reason of their great reputation for sanctity. The superiors of these convents bore the name of the god they served, and paid no visits except to the king.

The members of this order were consecrated to Quetzacoatl from their birth, and the father who intended his son for the worship of that god invited the superior of the convent to dinner. The latter sent one of the monks in his stead to the house, and the child was presented to him. The monk, taking the little creature in his arms, offered it to Quetzacoatl, pronouncing a prayer, and placing about its neck a collar called yanueli, which the child had to wear until its seventh year.

At the end of its second year the child was conducted to the superior, who made an incision in his breast, which, with the collar, was a sign of consecration. At the age of seven years he entered the seminary, after having first listened to a long moral discourse, in which he was reminded of the vow which had bound him to Quetzacoatl, and in which he was exhorted to conduct himself carefully, and to pray for his relatives and for the nation.

Another order, called Telpochtilztli ("reunion of children") was consecrated to Tezcatlipoca.

Children were bound to this supreme god by ceremonies similar to those just described, but they did not live in a community. In each quarter of the city, at sunset, they were called together by a superior to dance, and then to sing the praises of the gods.

Among the Totonacs was a brotherhood devoted to the worship of the goddess Centeotl, the members of which led a most austere life. Only men of sixty years of age, who were widowers and of good habits, could enter this order. Their number was limited; and not only the people, but the highest personages, the high-priest included, came to consult them. Seated on a bench, they listened to the questions addressed to them, with their eyes fixed on the ground, and their replies were received as oracles, even by the kings of Mexico. These monks employed their leisure in producing historical paintings, which they sent to the high-priest, that he might show them to the people.

The Aztec priests were generally of a literary character; and their austere life and their knowledge increased the influence which they owed to their sacred character. The Spanish missionaries, in spite of their prejudices, have always done justice to their morality and their chastity. They regarded them as men blinded by the devil, and not as impostors.

Although the external worship of the Aztecs was sanguinary, its similarities with many of the customs of the Catholic Church struck the Spaniards from the first. The cross of Tlaloc, the baptism of the new-born, the auricular confession, the vows of chastity, the monastic orders, etc., led the first missionaries to believe that the gospel had been preached in Anahuac at the time of the origin of Christianity; and in Quetzacoatl, who taught charity, gentleness, and peace, they thought they saw a disciple of Jesus Christ. Modern science has dispelled these illusions, as well as those that ascribe an Egyptian, a European, or a Hindoo origin to the people of Mexico. The Chichimecs, the Toltecs, and the Aztecs were at least American peoples, even if they were not autochthons. As to their civilizers, they cannot rationally be ranked among the disciples of Christ, but possibly they may have been sectaries of Buddha.

Biart, Lucien. The Aztecs: Their History, Manners, and Customs. Translated by John Leslie Garner, A.C. McClurg & Co, 1900.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.