Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From The Memoirs of the Conquistador Bernal Diaz del Castillo, published in 1552 and translated by John Ingram Lockhart.

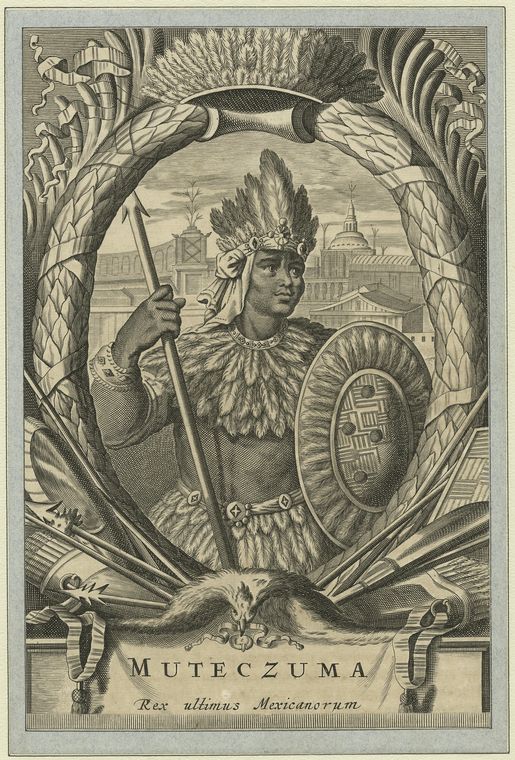

The mighty Motecusuma may have been about this time in the fortieth year of his age. He was tall of stature, of slender make, and rather thin, but the symmetry of his body was beautiful. His complexion was not very brown, merely approaching to that of the inhabitants in general. The hair of his head was not very long, excepting where it hung thickly down over his ears, which were quite hidden by it. His black beard, though thin, looked handsome. His countenance was rather of an elongated form, but cheerful; and his fine eyes had the expression of love or severity, at the proper moments.

He was particularly clean in his person, and took a bath every evening. Besides a number of concubines, who were all daughters of persons of rank and quality, he had two lawful wives of royal extraction, whom, how- ever, he visited secretly without any one daring to observe it, save his most confidential servants. He was perfectly innocent of any unnatural crimes. The dress he had on one day was not worn again until four days had elapsed.

In the halls adjoining his own private apartments there was always a guard of 2000 men of quality, in waiting: with whom, however, he never held any conversation unless to give them orders or to receive some intelligence from them. Whenever for this purpose they entered his apartment, they had first to take off their rich costumes and put on meaner garments, though these were always neat and clean; and were only allowed to enter into his presence barefooted, with eyes cast down.

No person durst look at him full in the face, and during the three prostrations which they were obliged to make before they could approach him, they pronounced these words: "Lord! my Lord! sublime Lord!" Everything that was communicated to him was to be said in few words, the eyes of the speaker being constantly cast down, and on leaving the monarch's presence he walked backwards out of the room. I also remarked that even princes and other great personages who come to Mexico respecting law-suits, or on other business from the interior of the country, always took off their shoes and changed their whole dress for one of a meaner appearance when they entered his palace.

Neither were they allowed to enter the palace straightway, but had to show themselves for a considerable time outside the doors ; as it would have been considered want of respect to the monarch if this had been omitted.

Above 300 kinds of dishes were served up for Motecusuma's dinner from his kitchen, underneath which were placed pans of porcelain filled with fire, to keep them warm. Three hundred dishes of various kinds were served up for him alone, and above 1000 for the persons in waiting. He sometimes, but very seldom, accompanied by the chief officers of his household, ordered the dinner himself, and desired that the best dishes and various kinds of birds should be called over to him.

We were told that the flesh of young children, as a very dainty bit, was also set before him sometimes by way of a relish. Whether there was any truth in this we could not possibly discover; on account of the great variety of dishes, consisting in fowls, turkeys, pheasants, partridges, quails, tame and wild geese, venison, musk swine, pigeons, hares, rabbits, and of numerous other birds and beasts; besides which there were various other kinds of provisions, indeed it would have been no easy task to call them all over by name.

This I know however, for certain, that after Cortes had reproached him for the human sacrifices and the eating of human flesh, he issued orders that no dishes of that nature should again be brought to his table.

I will, however, drop this subject, and rather relate how the monarch was waited on while he sat at dinner. If the weather was cold a large fire was made with a kind of charcoal made of the bark of trees, which emitted no smoke, but threw out a delicious perfume; and that his majesty might not feel any inconvenience from too great a heat, a screen was placed between his person and the fire, made of gold, and adorned with all manner of figures of their gods.

The chair on which he sat was rather low, but supplied with soft cushions, and was beautifully carved; the table was very little higher than this, but perfectly corresponded with his seat. It was covered with white cloths, and one of a larger size. Four very neat and pretty young women held before the monarch a species of round pitcher, called by them Xicales, filled with water to wash his hands in. The water was caught in other vessels, and then the young women presented him with towels to dry his hands. Two other women brought him maise-bread baked with eggs.

Before, howerer, Motecusuma began his dinner, a kind of wooden screen, strongly gilt, was placed before him, that no one might see him while eating, and the young women stood at a distance. Next four elderly men, of high rank, were admitted to his table; whom he addressed from time to time, or put some questions to them. Sometimes he would offer them a plate of some of his viands, which was considered a mark of great favour. These grey-headed old men, who were so highly honoured, were, as we subsequently learnt, his nearest relations, most trustworthy counsellors and chief justices. Whenever he ordered any victuals to be presented them, they ate it standing, in the deepest veneration, though without daring to look at him full in the face. The dishes in which the dinner was served up were of variegated and black porcelain, made at Cholulla. While the monarch was at table, his courtiers, and those who were in waiting in the halls adjoining, had to maintain strict silence.

After the hot dishes had been removed, every kind of fruit which the country produced were set on the table; of which, however, Motecusuma ate very little. Every now and then was handed to him a golden pitcher filled with a kind of liquor made from the cacao, which is of a very exciting nature. Though we did not pay any particular attention to the circumstance at the time, yet I saw about fifty large pitchers filled with the same liquor brought in all frothy. This beverage was also presented to the monarch by women, but all with the profoundest veneration.

Sometimes during dinner time, he would have ugly Indian hump-backed dwarfs, who acted as buffoons and performed antics for his amusement. At another time he would have jesters to enliven him with their witticisms. Others again danced and sung before him. Motecusuma took great delight in these entertainments, and ordered the broken victuals and pitchers of cacao liquor to be distributed among these performers. As soon as he had finished his dinner the four women cleared the cloths and brought him water to wash his hands. During this interval he discoursed a little with the four old men, and then left table to enjoy his afternoon's nap.

After the monarch had dined, dinner was served up for the men on duty and the other officers of his household, and I have often counted more than 1000 dishes on the table, of the kinds above mentioned. These were then followed, according to the Mexican custom, by the frothing jugs of cacao liquor; certainly 2000 of them, after which came different kinds of fruit in great abundance.

Next the women dined, who superintended the baking department; and those who made the cacao liquor, with the young women who waited upon the monarch. Indeed, the daily expense of these dinners alone must have been very great!

Besides these servants there were numerous butlers, house-stewards, treasurers, cooks, and superintendents of maise-magazines. Indeed there is so much to be said about these that I scarcely knew where to commence, and we could not help wondering that everything was done with such perfect order. I had almost forgotten to mention, that during dinner-time, two other young women of great beauty brought the monarch small cakes, as white as snow, made of eggs and other very nourishing ingredients, on plates covered with clean napkins; also a kind of long-shaped bread, likewise made of very substantial things, and some pachol, which is a kind of wafer-cake.

They then presented him with three beautifully painted and gilt tubes, which were filled with liquid amber, and a herb called by the Indians tabaco. After the dinner had been cleared away and the singing and dancing done, one of these tubes was lighted, and the monarch took the smoke into his mouth, and after he had done this a short time, he fell asleep.

About this time a celebrated cazique, whom we called Tapia, was Motecusuma's chief steward: he kept an account of the whole of Motecusuma's revenue, in large books of paper which the Mexicans call Amatl. A whole house was filled with such large books of accounts.

Motecusuma had also two arsenals filled with arms of every description, of which many were ornamented with gold and precious stones. These arms consisted in shields of different sizes, sabres, and a species of broadsword, which is wielded with both hands, the edge furnished with flint stones, so extremely sharp that they cut much better than our Spanish swords: further, lances of greater length than ours, with spikes at their end, full one fathom in length, likewise furnished with several sharp flint stones. The pikes are so very sharp and hard that they will pierce the strongest shield, and cut like a razor; so that the Mexicans even shave themselves with these stones.

Then there were excellent bows and arrows, pikes with single and double points, and the proper thongs to throw them with; slings with round stones purposely made for them; also a species of large shield, so ingeniously constructed that it could be rolled up when not wanted: they are only unrolled on the field of battle, and completely cover the whole body from the head to the feet. Further, we saw here a great variety of cuirasses made of quilted cotton, which were outwardly adorned with soft feathers of different colours, and looked like uniforms; morions and helmets constructed of wood and bones, likewise adorned with feathers. There were always artificers at work, who continually augmented this store of arms; and the arsenals were under the care of particular personages, who also superintended the works.

Motecusuma had likewise a variety of aviaries, and it is indeed with difficulty that I constrain myself from going into too minute a detail respecting these. I will confine myself by stating that we saw here every kind of eagle, from the king's eagle to the smallest kind included, and every species of bird, from the largest known to the little colibris, in their full splendour of plumage. Here were also to be seen those birds from which the Mexicans take the green-coloured feathers of which they manufacture their beautiful feathered stuffs. These last-mentioned birds very much resemble our Spanish jays, and are called by the Indians quezales. The species of sparrows were particularly curious, having five distinct colours in their plumage—green, red, white, yellow, and blue; I have, however, forgotten their Mexican name. There were such vast numbers of parrots, and such a variety of species, that I cannot remember all their names; and geese of the richest plumage, and other large birds. These were, at stated periods, stripped of their feathers, in order that new ones might grow in their place.

All these birds had appropriate places to breed in, and were under the care of several Indians of both sexes, who had to keep the nests clean, give to each kind its proper food, and set the birds for breeding. In the courtyard belonging to this building, there was a large basin of sweet water, in which, besides other water fowls, there was a particularly beautiful bird, with long legs, its body, wings, and tail variously coloured, and is called at Cuba, where it is also found, the ipiris.

In another large building, numbers of idols were erected, and these, it is said, were the most terrible of all their gods. Near these were kept all manner of beautiful animals, tigers, lions of two different kinds, of which one had the shape of a wolf, and was called a jackal; there were also foxes, and other small beasts of prey. Most of these animals had been bred here, and were fed with wild deers' flesh, turkeys, dogs, and sometimes, as I have been assured, with the offal of human beings.

Respecting the abominable human sacrifices of these people, the following was communicated to us: The breast of the unhappy victim destined to be sacrificed was ripped open with a knife made of sharp flint; the throbbing heart was then torn out, and immediately offered to the idol-god in whose honour the sacrifice had been instituted. After this, the head, arms, and legs were cut off and eaten at their banquets, with the exception of the head, which was saved, and hung to a beam appropriated for that purpose. No other part of the body was eaten, but the remainder was thrown to the beasts which were kept in those abominable dens, in which there were also vipers and other poisonous serpents, and, among the latter in particular, a species at the end of whose tail there was a kind of rattle. This last-mentioned serpent, which is the most dangerous, was kept in a cabin of a diversified form, in which a quantity of feathers had been strewed: here it laid its eggs, and it was fed with the flesh of dogs and of human beings who had been sacrificed. We were positively told that, after we had been beaten out of the city of Mexico, and had lost 850 of our men, these horrible beasts were fed for many successive days with the bodies of our unfortunate countrymen. Indeed, when all the tigers and lions roared together, with the bowlings of the jackals and foxes, and hissing of the serpents, it was quite fearful, and you could not suppose otherwise than that you were in hell.

I will now, however, turn to another subject, and rather acquaint my readers with the skilful arts practised among the Mexicans: among which I will first mention the sculptors, and the gold and silversmiths, who were clever in working and smelting gold, and would have astonished the most celebrated of our Spanish goldsmiths: the number of these was very great, and the most skilful lived at a place called Ezcapuzalco, about four miles from Mexico. After these came the very skilful masters in cutting and polishing precious stones, and the calchihuis, which resemble the emerald. Then follow the great masters in painting, and decorators in feathers, and the wonderful sculptors. Even at this day there are living in Mexico three Indian artists, named Marcos de Aguino, Juan de la Cruz, and El Crespello, who have severally reached to such great proficiency in the art of painting and sculpture, that they may be compared to an Apelles, or our contemporaries Michael Angelo and Berruguete.

The women were particularly skilful in weaving and embroidery, and they manufactured quantities of the finest stuffs, interwoven with feathers. The commoner stuffs, for daily use, came from some townships in the province of Costatlan, which lay on the north coast, not far from Vera Cruz, where we first landed with Cortes.

The concubines in the palace of Motecusuma who were all daughters of distinguished men were employed in manufacturing the most beautiful stuffs, interwoven with feathers. Similar manufactures were made by certain kind of women who dwelt secluded in cloisters, as our nuns do. Of these nuns there were great numbers, and they lived in the neighbourhood of the great temple of Huitzilopochtli. Fathers sometimes brought their daughters from a pious feeling, or in honour of some female idol, the protectress of marriage, into these habitations, where they remained until they were married.

The powerful Motecusuma had also a number of dancers and clowns: some danced in stilts, tumbled, and performed a variety of other antics for the monarch's entertainment: a whole quarter of the city was inhabited by these performers, and their only occupation consisted in such like performances. Lastly, Motecusuma had in his service great numbers of stone-cutters, masons, and carpenters, who were solely employed in the royal palaces.

Above all, I must not forget to mention here his gardens for the culture of flowers, trees, and vegetables, of which there were various kinds. In these gardens were also numerous baths, wells, basins, and ponds full of limpid water, which regularly ebbed and flowed. All this was enlivened by endless varieties of small birds, which sang among the trees. Also the plantations of medical plants and vegetables are well worthy of our notice: these were kept in proper order by a large body of gardeners. All the baths, wells, ponds, and buildings were substantially constructed of stonework, as also the theatres where the singers and dancers performed. There were upon the whole so many remarkable things for my observation in these gardens and throughout the whole town, that I can scarcely find words to express the astonishment I felt at the pomp and splendour of the Mexican monarch.

In the meantime, I am become as tired in noting down these things as the kind reader will be in perusing them: I will, therefore, close this chapter, and acquaint the reader how our general, accompanied by many of his officers, went to view the Tlatelulco, or great square of Mexico; on which occasion we also ascended the great temple, where stood the idols Tetzcatlipuca and Huitzilopochtli. This was the first time Cortes left his head-quarters to perambulate the city.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo, The Memoirs of the Conquistador Bernal Diaz del Castillo, John Ingram Lockhart, trans. (London: J. Hatchard and Son, 1844).

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.