Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Glimpses of Welsh Life and Character by Marie Trevelyan, 1893.

Among the earliest and most curious forms of amusements in Wales, was that of "trying the mettle" of the young men.

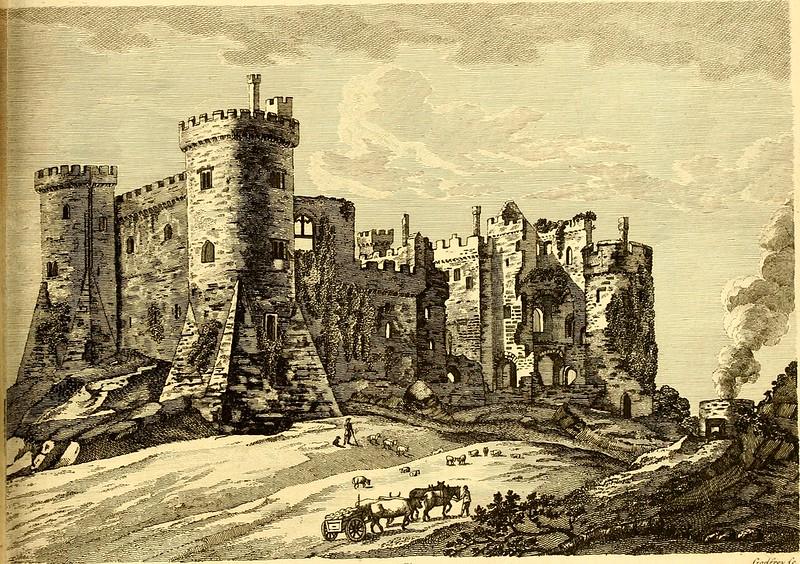

According to the oldest records, wild beasts were kept in strong wooden cages in the great courtyards of the castles. From these menageries, bulls, stags, bears, and wolves were in turn let loose at Christmas, Easter, and Whitsuntide, and the young men were called upon to exhibit their prowess in encounters with these formidable animals. Sometimes a bear or a wolf bore the reputation of being very ferocious, and the "mettle" of the youthful Celt was tried to the utmost. Then it was that strong arm and agile movement meant life, and the least wavering on the part of the youth might end in death. If the young man conquered the animal in the first adventure, it was considered a mark of splendid skill; and, after that, he was never again called upon to exercise his strength in so rude and barbarous a fashion.

Later on, the amusements of men of "gentle blood" appeared to have consisted chiefly of fierce personal encounters. It was the custom among young Welshmen to strut to and fro, boasting about the strength, though by no means the length of their sturdy limbs, and challenging the Normans and other strangers to wrestle, leap, dance, sing, or fight. The Welsh would pour out a stream of abuse against the Normans and their courage, and each would promise the other to fight and do his worst.

After the challenge an adjournment was made, during which the combatants armed themselves for the fray. Previous to the encounter, the opponents went to the priest to be shriven, and then the godly man would give wholesome warning to the extremely mettlesome youth, who daringly accepted, or provoked the challenge of a man accustomed to fighting from his boyhood up.

All the men at arms assembled to witness the fight, and, to use the actual words of a short and strong Welshman who had to encounter a gigantic opponent, "the bigger the man the better the mark."

A terrible scene then ensued. The javelin, the long iron grapple, the sword all were used in the fray, and it must have "Seen a sickening moment, when the combatants fell, and rolling together in the dust, were still further maddened by the yells of the men, and the shrieks of the ladies, in the gallery overlooking the great courtyard.

In Glamorganshire, the name Turberville is commonly held to have been bestowed upon the founder of the family for his fighting propensities. Some authorities go so far as to say he derived his name from his reputation as a "town troubler." However this may be, his characteristics appear to have been transmitted to many of his posterity, and the records of Glamorgan show that in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, there were numerous headstrong men bearing this name, whose chief delight was fighting and the fray. One of these fighting Turbervilles figures in the family history of Sir Rhys ap Thomas. An old chronicle, bearing date of A.D. 1460-70, reads thus:

"Thomas ap Gruffydd, the father of Sir Rhys ap Thomas, who helped Henry VII. to the throne, was famous for his boldness and skill in tilt and tournament, as he was in single combat. He had several encounters in the vale of Towey, particularly with one Henry ap Gwilym, who repeatedly challenged him, and was constantly vanquished. A quarrel with William, Earl of Pembroke, brought upon him another adversary, whose adventures were attended with some humorous circumstances. The Earl's quarrel was taken up by one Turberville, a noted swashbuckler of that day, 'one that would fight on anie slight occasion, not much heeding the cause.' Turberville sent in his defiance, to Thomas ap Gruffyd, by one of the Earl's retainers."

"Go tell the knave," said he, "that if he will not accept my challenge, I will ferret him out of his conie berrie, the Castle of Abermarlais." Thomas received this message very jocosely. "By my faith," said he, "if thy master is in such haste to be killed, I would that he should choose some other person to undertake the office of executioner."

This reply much provoked the challenger; and in a rage he set out for Abermarlais. Entering the gate, the first person whom he encountered was Thomas ap Gruffyd himself, sitting at his ease, dressed in a plain frock gown, whom he took for the porter. "Tell me, fellow," said Turberville, '"is thy master Thomas ap Gruffyd within?" "Sir," answered Thomas, "he is at no great distance; if thou wouldst have aught with him, I will hear thy commands."

"Then tell him," said he, "that here is one Turberville would fain speak with him." Thomas, hearing his name, and seeing the fury he was in, could scarce refrain from laughing in his face; but restraining himself, he said he would acquaint his master; and on going into his room, he sent two or three servants to call Turberville in. Turberville no sooner saw Thomas ap Gruffyd than, without making any apology for the mistake he had committed, he taxed him roundly for his contempt of so great a person as the Earl of Pembroke.

"In good time, sir," said Thomas; "is not my lord of Pembroke of sufficient courage to undertake his own quarrels, without the aid of such a swasher as thyself?"

"Yes, certainly," said Turberville, "but thou art too much beneath his place and dignity; and he has left thy chastisement to me."

"Well then," said Thomas, in excellent humour, "if thou wouldst even have it so, where would it please thee that thou wouldst have me go to school?" "Where thou wilt, or darest," said Turberville. "Thou comest here with harsh compliments," said, Thomas. "I am not ignorant, however, that as the accepter of thy challenge, both time, place, and weapons are in my choice; but I ween that it is not the fashion for scholars to appoint where the master shall correct them." After this parley, Thomas fixed on Herefordshire for the scene of the combat.

Here the champions met accordingly, when at the first onset Thomas unhorsed his adversary, and cast him to the ground, and by the fall broke his back.

The next engagement of this kind in which Thomas ap Gruffyd took part was in Merionethshire, when his antagonist, David Gough, was slain. Having afterwards thrown himself on the ground to rest, and being unarmed, he was treacherously stabbed by one of his enemy's retainers.

Thomas ap Gruffyd's two elder sons, Morgan and David, immediately after their father's death became warm partisans on opposite sides of the rival houses of York and Lancaster, and both perished in that civil warfare.

Trevelyan, Marie. Glimpses of Welsh Life and Character. J. Hogg, 1893.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.