Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Early Travellers in Scotland by Peter Hume Brown, 1891

Jorevin de Rocheford (1661?).

The following narrative is taken from the fourth volume of the Antiquarian Repertory (1809). It is a translation from a very scarce book of travels published at Paris in 1672. The name of its author does not appear in the French biographical collections; and nothing seems to be known of him except what is implied in his own narrative of his travels, which extended over England and Ireland as well as Scotland. From certain of his remarks we gather that his visit to Scotland took place shortly after the Restoration.

Antiquarian Repertory, vol. iv., p. 599.

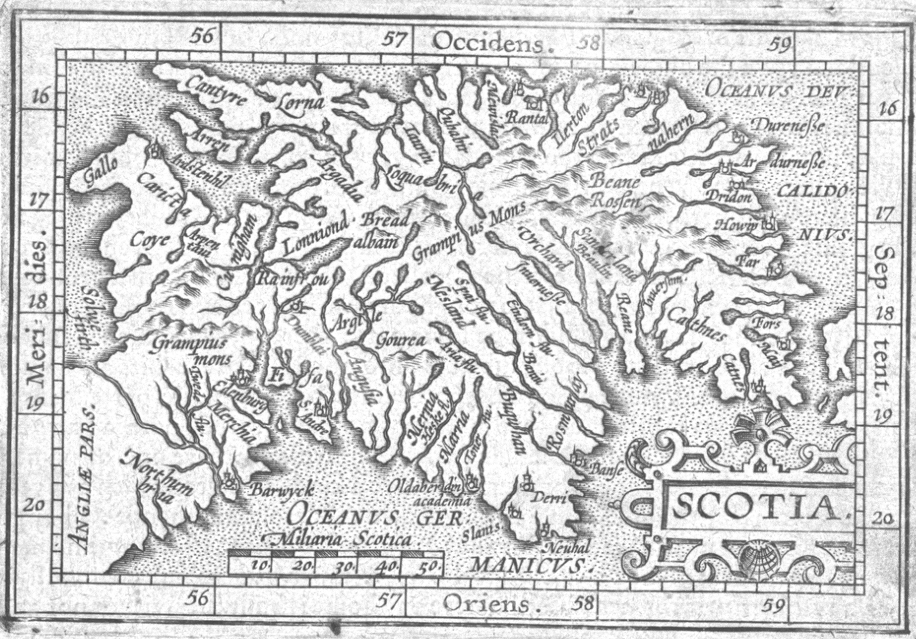

The kingdom of Scotland is ordinarily divided into two parts, which are on this side and beyond the river Tay; each part is subdivided into provinces, called Chirifdomes. This kingdom is bounded on the north side by the Orcade Islands, Schetland and Farro, inhabited only by fishermen, and persons who subsist almost entirely on fish, and a little game they take by hunting in the mountains, with which these islands are generally covered. It is bordered on the west by the Ebudes Islands, and divers other small islets, which are at the entrance of an almost infinite number of great gulfs advanced into the kingdom, which they furnish with fish, in abundance. But the country is so mountainous and so ingrateful in some places, that it is not worth cultivation; and the cold so intense as scarcely to permit grain to ripen. On the south is the kingdom of England; and on the east the German Sea, otherwise the fishy sea, or Haringzee, because there are caught by the Flemish and Dutch the salmoncod, but principally herrings, with which, after salting, they serve France and other kingdoms; this fishery making the best part of their riches.

I know very well that the northern part of this kingdom, beyond the river Tay, is almost uninhabited, on account of the high mountains, which are only rocks, where there is no want of game in great quantities; but there grows but very little corn; which obliges the inhabitants of the interior parts of the country to subsist on fish, which they dry by means of the great cold, after having caught them in the lakes, which are to be found all over the kingdom; and some of the villages by the sea-side export as much fish as furnishes them with corn and other necessaries of life. It is said, that there are certain provinces on that side of the country, where the men are truly savage, and have neither law nor religion, and support a miserable existence by what they can catch. But I likewise know, that the southern part of the kingdom on this side the Tay contains many fine towns, good sea-ports, great tracts of fertile land, and beautiful meadows filled with herds of all sorts of cattle; but the extreme cold prevents their growing to the common size, as is the case all over Europe. The principal towns are, Edinbourg, Lyth, Sterling, Glasgo, Saint Andreau, Abernethy, Dunkeld, Brechin, the old and new Aberdeen, the port of Cromary, Dornok, the town of St Johnstone, where are the four fine castles of Scotland.

After having passed through Nieuwark that is on the side of the gulf of Dunbriton, which lay on my left hand, to enter into a country surrounded almost on all sides by mountains, I descended into some very agreeable valleys, as Kemakoom, &c. From thence I followed a small river, where the country grew a little better, to go to Paslet, on a river forded by a large bridge abutting to the castle, where there is a very spacious garden enclosed by thick walls of hewn stone. It was once a rich abbey, as I discovered by a mitre and cross, that appeared half demolished, upon one of the gates of the castle, which was the abbey house. Those who go from Krinock l to Glasgo pass from Kemakoom by Reinfreu; but the way is full of marshes, difficult to pass over, and where there is a boat which does not work on Sundays, according to the custom of England, as it happened when I was travelling that road; which caused me, in order to avoid these difficulties, to change my route, which was after Paislet, to enter into a fine country upon the banks of the river Clyd, which I followed to the suburbs of Glasgo, joined to the town by a large bridge. This I passed before I could enter Glasgo.

Glasgo

Glasgo is the second town in the kingdom of Scotland, situated upon a hill that extends gently to the brink of the river of Clyd, which is capable of bearing vessels, since the tide rises here a little from the gulf of Dunbritton, into which it empties itself; so that vessels can come from Ireland to Glasgo. The streets of Glasgo are large and handsome, as if belonging to a new town; but the houses are only of wood, ornamented with carving. Here live several rich shopkeepers. As soon as I had passed the bridge, I came to the entry of two broad streets. In the first is a large building, being the hospital of the merchants, and farther on the market-place, and town-hall, built with large stones, with a square tower being the town clock-house; under which is the guard-house, as in all the towns of consequence in England.

Although Glasgo has no other fortification, that does not prevent it from being very strong, for towards the east side it is elevated upon a scarped rock, the foot whereof is washed by a little river, very convenient to that part of the town through which it passes. I lodged in this fine large street. The son of the owner of the house, being then studying philosophy at the university, conducted me everywhere, in order to point out to me what was most remarkable in the town. He began by the college, of which he showed me the library, which is nothing equal to that I saw at Oxford. From hence I came into a large and very fine garden, filled with all kinds of fruit-trees, deemed scarce in that country.

At length we entered into the great court, the facade whereof is the great body of the house, newly built, under which are the classes sustaining the galleries, and lodgings for the scholars and students. He introduced me to the regent in philosophy, who asked me many things respecting the colleges and universities of France, principally of that of the Sorbonne; upon which he told me, he was astonished that throughout all Europe there was not one uniform faith, since we all sought the same end to go to Paradise, the road to which we Catholics had made so difficult, although God by his sufferings and mercy had rendered it very easy, and was desirous all the world should enter. To whom I answered that God was at once both merciful and just, and that we could not arrive at heaven but by the difficulties and labours that he himself had suffered, in order to point out the way to us. I was unwilling to continue this discourse, whereby I could learn nothing useful in my voyage, wherefore I took leave of him, in order to visit the metropolitan church of the archbishopric.

It is perhaps the longest and best built in the kingdom, and ornamented round about with many figures of saints, some of which were thrown down and broken at the time the Protestants made themselves masters of it, after having driven out the Catholics. The chapel behind the choir contains some very remarkable tombs. There are two high towers over the principal doors of this handsome church. The archbishop's palace is large, and very near it.

We went and walked in the market-place, where a market is held twice a week; it is across-way, formed by the handsomest streets in the town; on that towards, the left hand is the butchery, and the great general hospital. In the environs of Glasgo are several pits, from whence they dig very good coal, which is used for fires instead of wood in winter time, here severe, and of long duration. One had only need to look at the sphere to know this, and at the time too, when the days in summer are more than twenty-two hours long, since the sun sets only three or four hours at night; so that as the days are long in summer, they are proportionately short in winter.

I left Glasgo to go to Edinbourg, and passed over a great plain, where stands Cader, and afterwards Cartelok, where there is a castle on a river. And shortly after, towards my left hand, I left a great castle in the bottom of a little valley, at the foot of the mountains, from whence issues a little river that I passed at Falkirk. Here great quantities of stuffs and cloths of all sorts are made. Leaving it, on the left hand one sees the extremity of the gulf of Edinbourg, where the river of Forthna empties itself near the town of Stirling, situated at the foot of a range of the highest mountains in Scotland, to go to Lithquo.

Lithquo

Lithquo is situated in a very good country, although it is environed by high mountains. Ib stands on the banks of a large lake, with a castle on the highest part of the town, being on a rock commanding its whole-extent. It is flanked by several large towers, which render it one of the strongest places in the kingdom. There is a very handsome church at one end of the market-place, in the center of which is a fountain, in a bason which receives its waters. The chief street crosses the market-place and the whole town. Here is a manufactory of cloth and fine linen. I left this place, and passed through Kalkester to go to Edenburgh.

Edenburgh

Edenburgh is the capital town, and the handsomest of the kingdom of Scotland, distant only a mile from the sea, where Lith is its sea-port. It stands on a hill, which it entirely occupies. This hill, on the side whereon the castle is built, is scarped down as steep as a wall, which adds to its strength, as it is accessible only on one side, which is therefore doubly fortified with bastions, and a large ditch cut sloping into the rock. I arrived by the suburbs, at the foot of the castle where at the entry is the market-place, which forms the beginning of a great street in the lower town, called Couguet. On coming into this place, one is first struck with the appearance of a handsome fountain, and, a little higher up, with the grand hospital or alms-house for the poor: there is no one but would at first sight take it for a palace. You ascend to it by a long staircase, which ends before a platform facing the entry at the great gate. The portico is supported by several columns, and the arms and statue of the founder, with a tablet of black marble, on which there is an inscription, signifying, that he was a very rich merchant, who died without children. There are four large pavilions, ornamented with little turrets, connected by four large wings, forming a square court in the middle, with galleries sustained by columns, serving for communications to the apartments of this great edifice.

One might pass much time in considering the pieces of sculpture and engraving in these galleries, the magnitude of its chambers and halls, and the good order observed in this great hospital. Its garden is the walk and place of recreation for the citizens, but a stranger cannot be admitted without the introduction of some inhabitant. You will there see a bowling-green, as in many other places in England: it is a smooth even meadow, resembling a green carpet, a quantity of fruit-trees, and a well-kept kitchen-garden. .From thence I proceeded along this great street, to see some ancient tombs in a large burial-ground, and, farther on, the college of the university. I was shown a pretty good library, but the building is not remarkable; it has a court, and the schools are round about it.

This lower town is inhabited by many workmen and mechanics, who, though they do not ennoble the quarter, render it the most populous. Here are a number of little narrow streets mounting into the great one, that forms the middle of the town, and which from the castle extends gently to the bottom of the hill, that seems on two sides enclosed by a valley, which serves for a ditch; in one is what we have called the lower town, and in the other are the gardens, separated from the town by a great wall. I lodged at Edenburgh in the house of a French cook, who directed me to the merchant on whom I had taken a bill of exchange at London. He took me into the castle, which one may call impregnable, on account of its situation, since it is elevated on a rock scarped on every side, except that which looks to the town, by which we entered after having passed the drawbridge, defended by a strong half-moon, where there is no want of cannon.

This brings to my mind one seen in entering the court, which is of so great a length and breadth, that two persons have laid in it as much at their ease as in a bed. The people of the castle tell a story of it more pleasant than true: they say it was made in order to carry to the port of Lyth against such enemies as might arrive by sea; we saw several of its bullets, of an almost immeasurable size. This court is large, with many buildings without symmetry. There are some lodgings, pretty well built, which formerly served for the residence of the kings of Scotland, and at present for the viceroys, when the King of England sends any; for at the time I was there, there was only the Grand Chancellor, who had almost the same authority and power as a viceroy.

Descending from this castle by the great street, one may see its palace, and, a little before the great market-place, the custom-house, where are the king's weights. This street is so wide that it seems a market-place throughout its whole extent. The cathedral church is in the middle; its only ornament is a high square tower. Beside it is the parliament-house, where the chancellor resides. There are several large halls, well covered with tapestry, where the pleadings are held, and a fine court. In the great hall are several shop-keepers, who sell a thousand little curiosities. There is besides a large pavilion, having a little garden behind it, where there is a terrace commanding a view over all that part of the town called the Couguet, at the foot of the palace and pavilion where the chancellor resides. This fine large street serves for the ordinary walk of the citizens, who otherwise repair to the suburbs of Kanignet, in the ancient palace of the kings of Scotland.

This suburb is at the end of the great street, where there is another of the same size, and almost as handsome, which adjoins to the palace called the king's house, said to have been formerly an abbey, great appearances thereof being still remaining. In entering, you pass the first great court surrounded with lodgings for the officers; and from thence into a second, where appears the palace, composed of several small pavilions, intermixed with galleries and turrets, forming a wonderful symmetry; but it has been much damaged by fire. There is likewise the church, the cloisters, and the gardens of this ancient abbey. This suburb is separated from the town by a gate with a bell tower, wherein is a clock; and on one side appears the little suburb of Leyth-oye, the way leading to the port of Leyth. In the middle of the street is a very fine hospital, which carries some marks of having formerly been a convent, and close to it a handsome church, once belonging to a priory, when the Catholic religion was prevalent in the kingdom of Scotland,

It is difficult to hear mass at Edinburgh, for it is strictly forbidden to be celebrated, although there are some Catholics, Flemings and Frenchmen, who dwell there, with whom I made an acquaintance, and who visited me sometimes in my inn. They one day begged me to go a shooting with them, assuring me that we should not return without each of us filling his bag with game; nevertheless, it was not this consideration that caused me to go, but rather the hope of learning some curiosity of the country and the city of Edinburgh, where these gentlemen had resided a long time. We set out at four o'clock in the morning, being four in company, with three good dogs. We came to the sea-side on a great beach, from whence the tide had retired, where we found some water-fowl, of which we killed three, and six large wood-cocks, and near this place were some little hills covered with heath and bushes, where we went to beat for hares and rabbits, which frequently stroll near the sea-side. Our dogs put out a large leveret, which was soon knocked down. We then went to get some of our game cooked for breakfast, at a village not far off, and afterwards returned to hunt along that gulf which we coasted in going to Edenburgh, whither we carried, of our shooting, six young wild ducks, four wood-cocks, and two rabbits. I was very much fatigued, yet nevertheless lent my hand as heartily to the business as any present in getting the supper ready, in order to have it the sooner done; when in the combat that ensued, every one did wonders, where the glasses served for muskets, the wine for powder, and the bottles for bandileers; whence we returned from the field all conquerors and unwounded.

These gentlemen invited me several other times to go sporting with them, but I always refused, on account of the great fatigue I had undergone. I chose rather to visit Leyth, a mile distant from Edinburgh, from whence coaches set out every moment to go by a paved road over a large and very fertile plain. Seeing a gibbet in my way, I could not refrain from laughing, as it brought to my mind the many tricks played at Rome with the hangman's servant, who is obliged to carry a ladder from his house to the place of punishment, where his master is to execute the criminal. He, carrying this ladder, is mounted on a horse, led by a man with a drawn sword in his hand, to defend him. But let him do what he will, every one will have a stroke at him; some refresh him with pails of water, which they throw out of the windows; others embroider his clothes with handfuls of mud; some greet him with rotten melons, and others over- whelm him with stones, accompanied with this reproach, Boya, so odious among the Italians; they also pull his feet and ladder, to make him fall; insomuch that it is pleasant to see in what a pickle he arrives on the gallows. But in England it is not so, for the executions are performed only every six months; and it signifies nothing at what time the criminal is condemned to death, he being always kept till that day, and is taken from the gibbet to be interred on Good Friday.

Lyth

Lyth is a little trading town, and a good sea-port, situated at the mouth of the little river Lyth in the gulf of Edenburgh, which is above forty miles in length, and twelve broad at its entry, and before Lyth about eight. In the middle there is a small island, on which is an impregnable fort. There are many good harbours and large towns along this gulf, with mines yielding tin, lead, and sea-coal, in such quantities that the Flemish, the Dutch, the Danes and the Swedes, and even the French, are served from hence. Moreover in this same gulf they prepare salt, which the Dutch purchase to cure the fish catched in the Scotch seas; although many persons say this salt will not preserve them long, and that the things pickled with it are apt to spoil. But without straying from Lyth, I can say it is the most famous sea-port in Scotland, frequented, on account of its traffic, by all the nations in Europe; and it is at the mouth of this little river, which is so deep that the largest vessels can come up into the center of the town, and lie loaded along the quay, sometimes to the number of more than fifty.

The river forms the separation of a large village, which lies on the other side, to which you must pass over a stone bridge that joins it to the town. This village is the residence of fishermen and sailors, and here sometimes large vessels are built. On the same side is a citadel, close to the sea, which has almost ruined it by its waves, having undermined the bastions in such a manner, that it is as it were abandoned, for there is no garrison to guard it. Adjoining to the quay is a mole, fashioned like a wooden bridge, advancing more than two hundred paces into the sea, to prevent the sand brought by the tide from choking up the entrance of the port, which is extremely necessary for the town of Edenburgh, for the merchandizes that arrive by sea, or are shipped for foreign countries, principally for the north.

I returned to Edinburgh, and, after taking my leave of some French people of my acquaintance, departed for Barwick, by the following route. Leaving the town, I had the gulf on my left hand, and on my right the great road to Newcastle, near a small river at Nedrik where there is a castle. At Molsburg there is also a castle on a river, still within the agreeable view of this ; which one is obliged continually to follow, on account that the road is bordered by high mountains, which are impassable. Come to Trenat, where there are mines of very good coal, with which I saw several vessels loaded. The country where they are commonly found, is somewhat mountainous, and covered with bad soil, as hereabouts at Arington on a river. Here is a large market-place, and a fine street adjoining to the principal church, which it is said the French held a long time, when they made themselves masters of a good part of this kingdom, and from whence they were at length driven out, as I was informed by my landlord's son, in conducting me out of the town. I followed the river, full of good fish, particularly trout of a delicious taste; on it I saw a large castle, on the right hand, going to Linton, where I passed this river, which runs among the rocks. Shortly after, one has a view of the same gulf, passing over a country covered with sandhills to Dunbart.

The village is famous for its great fishery of herrings and salmon, which are carried into France and other parts of Europe. The port would be good for nothing, if the road, which is before it, was not covered by high rocks, which border these coasts. At the foot of these is a part of the village, the habitation of fishermen ; and another above it, where there is a fine large street. I lodged in the house of one who spoke French, and had served Louis the Thirteenth in the Scots Guards. He related to me many things that had happened in his time. He had been at the siege of Rochelle, the history of which he gave me, with many particulars. He treated me with fish of all sorts, among others, with a piece of salmon dressed in the French manner, and a pair of soles of prodigious size. The beer usually drank in Scotland is made without hops, they call it ale; it is cheaper than the English beer, which is the best in Europe.

From Dunbarton, through a champaign country, I next came to Cobrspech, whence, having passed some little mountains, I still followed the sea, and went through five or six small hamlets, in a plain near a river. The country hereabouts is but badly cultivated, and full of heaths, till I descended into a bottom to Aiton, where there is a castle on a river, which I crossed, and afterwards passed a high mountain, adjoining to some meadows near the sea-side, 4 and along the banks of a river, following which, I arrived at Berwick.

Barrwick

Barrwick is the first town by which I re-entered England, and, being a frontier to Scotland, has been fortified in different manners. There is in it at present a large garrison, as in a place of importance to this kingdom. It is bounded by the river Tweed, which empties itself into the sea, and has a great reflux, capable, but for sands at the entrance into its port, of bringing up large vessels. I arrived here about ten of the clock on a Sunday; the gates were then shut, it being church time, but were opened at eleven, as is the custom in all fortified places. Here is an upper and a lower town, which are both on the side of a hill, that slopes towards the river. On its top there is a ruined and abandoned castle, although its situation makes it appear impregnable; it is environed on one side by the ditch of the town, and on the other side by one of the same breadth, flanked by many round towers and thick walls, which enclose a large palace, in the middle of which rises a lofty keep, capable of a long resistance, and commanding all the environs of the town.

The high town encloses within its walls and ditches those of the lower, from which it is only separated by a ditch filled with water. In the upper town the streets are straight and handsome; but here are not many rich inhabitants, they rather preferring the lower town, in which there are many great palaces, similar to that which has been rebuilt near the great church. In all the open areas are great fountains, and in one of them the guard-house and public parade, before the town-hall or sessions house, over which is the clock-tower of the town; so that by walking over Barwick, I discovered it to be one of the greatest and most beautiful towns in England.

The greatest parts of the streets in the lower town are either up or down hill; but they are filled with many rich merchants, on account of the convenience and vicinity of its port, bordered by a large quay, along which the ships are ranged. There is not a stone bridge, in all England, longer or better built than that of Berwick, with sixteen large and wonderfully well-wrought arches; it is considered as one of the most remarkable curiosities of the kingdom.

Brown, Peter Hume. Early Travellers in Scotland. David Douglas, 1891.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.