Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

“Attitude Toward American Life,” from Americanization of the Finnish People in Houghton County, Michigan by Clemens Niemi, 1921.

We all have tendency to idealize impressive personalities who have either written books or composed music or other persons of fame who by their works have approached the innermost labyrinths of our nature. This analogy holds true of the immigrant also. He has idealized America, its great men before entering this side of the Atlantic. He has heard many stories about America, has pictured it to be a land of democracy, of freedom, of equality with no class distinction. No one would inquire here about his ancestry; his integrity, his character would only decide his future career.

He, also, has imagined how easily he could make his living here, even a “fortune" like so many of his friends he knew. But what did he find here upon his arrival? Stern reality faced him; he found himself in a new environment, in a new social milieu. He wondered, he stared at the magnificent skyscrapers, at the restless, furiously moving throngs that changed streets and avenues of American cosmopolitan cities into throbbing arteries.

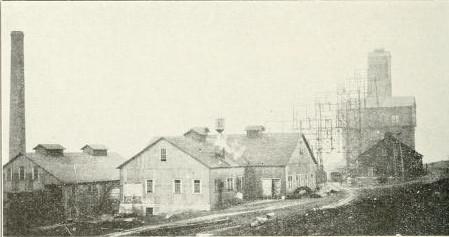

And when he traveled farther inland to meet his friends or relatives he arrived at a tiny mining village or town in which the shrieking whistles blew their tragic welcome. Now he had a general view of America he had so many times dreamed of.

After he had worked a few days he was ready to express his first impressions about America. "I had imagined America to be a beautiful country where aesthetic qualities are on a par with money," said a woman who had come here about twelve years ago. "At once on my arrival I was bitterly disappointed when I reached this mining town. The companies had heaped recklessly mountain-like rock piles in the neighborhood of residence sections. In addition, one could see miserable looking miners' huts scattered all along the muddy alleys and roads. As I contrasted conditions here with those in my native country I began to cry. I wept, I felt lonesome for days, weeks and months before I got used to the new surroundings. I would have gone back to Finland had I had money enough to buy my transportation ticket. But now it is different. I am used to all this. I have raised my children here and for their sake I will stay in America..." This woman had received a fairly good education in the old country.

Another woman who had gone through many hardships in Finland, said: "I came to stay with my daughter, but found everything disagreeable. The language, customs, food, in fact all seemed to be so strange that I thought to myself I would never remain here. I had missed my friends and relatives. I felt lonesome and would often burst into tears. I begged that I might go back to my home country, but all my imploring was in vain. Finally when nobody seemed to pay any attention to my crying I had to stop it myself. I have stayed with my daughter and now I feel perfectly at home. I am so glad after all that I came here. We have plenty of wholesome food and everything we need."

A man engaging in mining added: "I, as so many immigrants, had somewhat lonesome days on my arrival here. It was my inability to talk the English language that caused all the trouble. I thought I would not stay here very long, that as soon as I had earned enough money I would leave this country. I often remembered my friends with whom I had grown up. It seemed to be impossible to live here among strange people, to starve from the lack of congenial companionship. But as I had made nice savings and was about to depart I stopped to think a while. I asked myself why I should leave so soon? I had learned a few words, had learned to eat American dishes, to dress like Americans. In the true sense of the word America and I were now more intimate friends. I decided to remain here one more year. I did so and after that period I paid a visit to Finland, but found condition there so different that I could no longer tolerate their existing social order and that sharp class distinction. I soon left back for America."

A successful business man continued: "I came here to stay. First when I came here I worked in a mine. Then I started my business career and I am satisfied. No old country for me!"

All the interviews I had with these early settlers reflected, with a few exceptions, the same idea: America, because of its strange language, customs, first made somewhat disappointing impression on me, and to stay here longer seemed almost impossible.

But within a year or so his attitude toward American life became greatly modified. He learned to stammer a few broken words or phrases of the language and now the biggest of all the obstacles to cordial friendship between him and America was about to crumble down. The writer was told many times that one's inability to converse in the English language caused more hardships to the immigrant than any other factor. He, also, was economically better off here. Dishes which were regarded as luxuries in the old country were here every day necessities. He had liberal spending money in his pocket. He became acquainted with the American ways of doing things. He occasionally visited libraries, schools and other institutions, participated in the Fourth of July parade, watched how Americans celebrated their national holidays in public parks and there he bought an ice cream cone or pop, or he attended the movies.

All these created in him a desire to be like Americans. Gradually new traditions, new customs displaced the old ones and a peculiar dualism — a combination of the old and new ideals, recollections, convictions, experiences and sentiments filled his mind. Those values which, because of their intrinsic qualities, were of immediate benefit to him in his new environment, gained dominance over the old values. Now he began to see America in a different light.

"How proud I feel to be a naturalized American citizen!" exclaimed a young man who had come here under the age of nineteen and who was attending university. "When I arrived in America I thought I had done very foolishly to leave my native country whose blue lakes and rippling silvery creeks I loved so much. When I came to this side of the Atlantic I hoped so heartily that immigration authorities would turn me back to my native country. I realized what a mistake I had made. My inability to talk the English language made me sensitive. I looked to the American institutions with prejudice so long as I was ignorant about them and the whole American life loomed before my eyes as one unsolvable, obscure puzzle.

“But as I learned the language, learned to read American newspapers, became acquainted with American schools and other institutions, my attitude was changed. My sensitiveness disappeared, memories of my old country gradually vanished from my mind. My thoughts were more centered in this country and on my personal affairs as to how I could adapt myself the quickest possible way to the new environment. I was ready to draw my conclusions on public questions discussed in newspapers. Now I felt I was a part of this great democratic nation which I had so many times idealized. I felt I was unconsciously converted into Americanism through various steps.

"And when I visited art museums, city libraries, state capitols, universities, or when I attended patriotic meetings where "America" or "The Star Spangled Banner" were sung or played, I felt that unexplainable, lofty spirit of patriotism seize me. American traditions and history became clarified and I could distinctly picture before my eyes those brave forefathers of this country who stood for inalienable rights of mankind, who fought and fell bravely for the principles of humanity. Now America is all to me. Only like a flash of lightning old memories of the native country at times penetrate my mind, but they are ephemeral. The traditions of the old country are of secondary importance to me..."

These excerpts from the life histories of those interviewed indicate clearly what the newcomer's attitude toward American life was and how this attitude was gradually changed. What, then, were the Americanizing forces that initiated this change? They were economic betterment that found immediate response in the attitude of the immigrant, the limited knowledge of the language — a few broken words or phrases enabled him to participate in American life, and finally accidental or occasional contact with American institutions. These forces accelerated the Americanization process unconsciously.

Niemi, Clemens. Americanization of the Finnish People in Houghton County, Michigan. Finnish Daily Publishing, 1921.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.