So as I already mentioned in another article, my father worked as a mechanic for most of my early childhood. At first he worked for other companies (as a general shop mechanic), then when he had become well enough known he opened his own shop near a local Block Plant (where my mother also later found employment). After this failed endeavor (dad was a brilliant mechanic but such didn’t necessarily translate to the business world), he soon found gainful employment working for a High School friend who had a millwright business. There he learned Sheetmetal fabrication, welding, and Industrial Engineering skills, becoming an active (if unwilling) member of a union. When this friend and business owner retired early, dad then took over operation of the local full-service gas station in Wilderville. After years of selling gas for less money than it cost him (a typical rural service station sob story), dad resumed his occupation as a millwright -he and my brother worked together in this field over two decades- for most of his remaining days. But for those who really knew dad, these occupations just seemed a means to an end in order to pursue his greater goal: to excel at whatever he put his mind to; as an athlete, as a mechanic, an outdoors man, a fabricator, an amateur motocross racer, whatever he set his will upon. It is this very ethos that he also tried to cultivate within his two sons, and if mine and my brother’s uniquely diverse skill sets are any indicator, perhaps he succeeded in this endeavor as well.

One must also understand that fishing has always been a traditional pursuit within my father’s line, related in part to our heritage (specifically our line of descent from the Lummi tribe) but mostly as a means of sustenance. For members of my family, fishing was more than a hobby, it was a serious business; as it was our primary means of putting food on the table. So in my youth, nearly every weekend (when more pressing “chores” didn’t take precedence; such as the required gathering of 4-6 cord of firewood each year), one could find us down the Rogue, Illinois, Chetco, or Applegate rivers, “getting our line’s wet.” Dad was on a ‘first-name basis’ at all the local fisherman haunts, and so we were always well informed what fish were running, as well as what they were “hitting” on: sometimes we cast “spinners,” and at other times worked “hot-shots.” When the salmon spawned upstream we drifted roe, and plunked worms while the rivers were running high…eventually we even transitioned to “swatting flies” (although I must admit my casting was never what dad might have called “up to standard”). On weekends, whether rain, sleet or snow fell (with the exception of the latter motocross-focused summers) you could find us on the river; at times in mid-winter desperately trying to thaw our frozen reels and hands on the ‘red-eye’ propane heater, and/or wearing appropriately modified trash bags to keep at least some portion of our otherwise sodden bodies dry…but I digress.

At some influential point in the early 1970s, dad became fast friends with a man named Harley. Now, Harley was a drift boat operator/river guide, and dad became quickly enamored with the idea of also making an income as a guide. So, under the tutelage of this new found friend, dad borrowed a boat and over the course of many weekends, learned the finer art of drift boatsmanship. Having taken quite well to this new skill (helped in great part by his undeniable athleticism and legendary determination), dad and Harley then began implementing plans to build dad a pair of boats (a wood one for fishing trips upriver, and an aluminum one for whitewater trips down), with the intention to, at times, partner on lucrative guide trips through the Wild and Scenic portion of the Lower Rogue. So, for many following weekends and long nights on end after work, together they assembled dad’s new dream. To manage such an engineering feat not only required extensive woodworking skills, but also knowledge of aluminum fabrication and welding. It might also need to be mentioned here that members of my father’s line have always seemed to have an innate mechanical aptitude: a predilection for construction, fabrication, engineering and repair (and such latent ability has certainly assisted me in my pursuits in the arts, my passion for all things two-wheeled, and during my Arboricultural career), so for dad, acquiring such varied new skill-sets was really nothing out of the ordinary: merely another in a series of “mechanical puzzles” to be studied and solved.

The first boat to arrive at our property was the wooden one. Her intent and purpose was to be spent fishing any number of a series of “drifts” designated by local guides via the boat launch from which they started from and ended at: “"Schroeder Park to Ferry Hole”… “Griffith Park to Robinson Bridge,” etc. These references became part of my immediate family’s lexicon for (what seems at this point at least) the remainder of our lives. With each of these designations also came intimate knowledge of their different stills, riffles, holes; where to fish them, how to fish them, and all influenced (of course) by what variety of fish was actively running at that particular time of year. This was a tremendous amount of information to retain at such a formative point in life. One must also realize that in my family, asking questions was never really encouraged: rather, one was expected to always pay close attention, and then intuit a proper “solution” based upon this ever growing body of observations. One might say it was assumed that life did not present teaching opportunities, as much as learning opportunities. As such, when fishing one was expected to both know and anticipate whether one was to be using a baitcaster/hotshot combo, a spincaster with a “bright” Panther-Martin, and/or whether a wet-fly might best match the water conditions. Dad would at times offer an overriding declaration, but generally, we were not taught and encouraged, but rather, chastised for our failures. Regardless, imagine the body of ever-evolving knowledge my father or grandfather were able to accumulate over decades of such intensive observation, and likewise, the number of fish tales (and the like) available at their disposal: such as the time when my brother caught a duck mid-flight spin-casting at the merge point of the Rogue and Applegate, or when I caught my own ear trying to cast sinking-taper fly line…and yes, we had to endure many such humiliating anecdotes in public re-enactments (often at an outfitters): such was just a life of learning within my family.

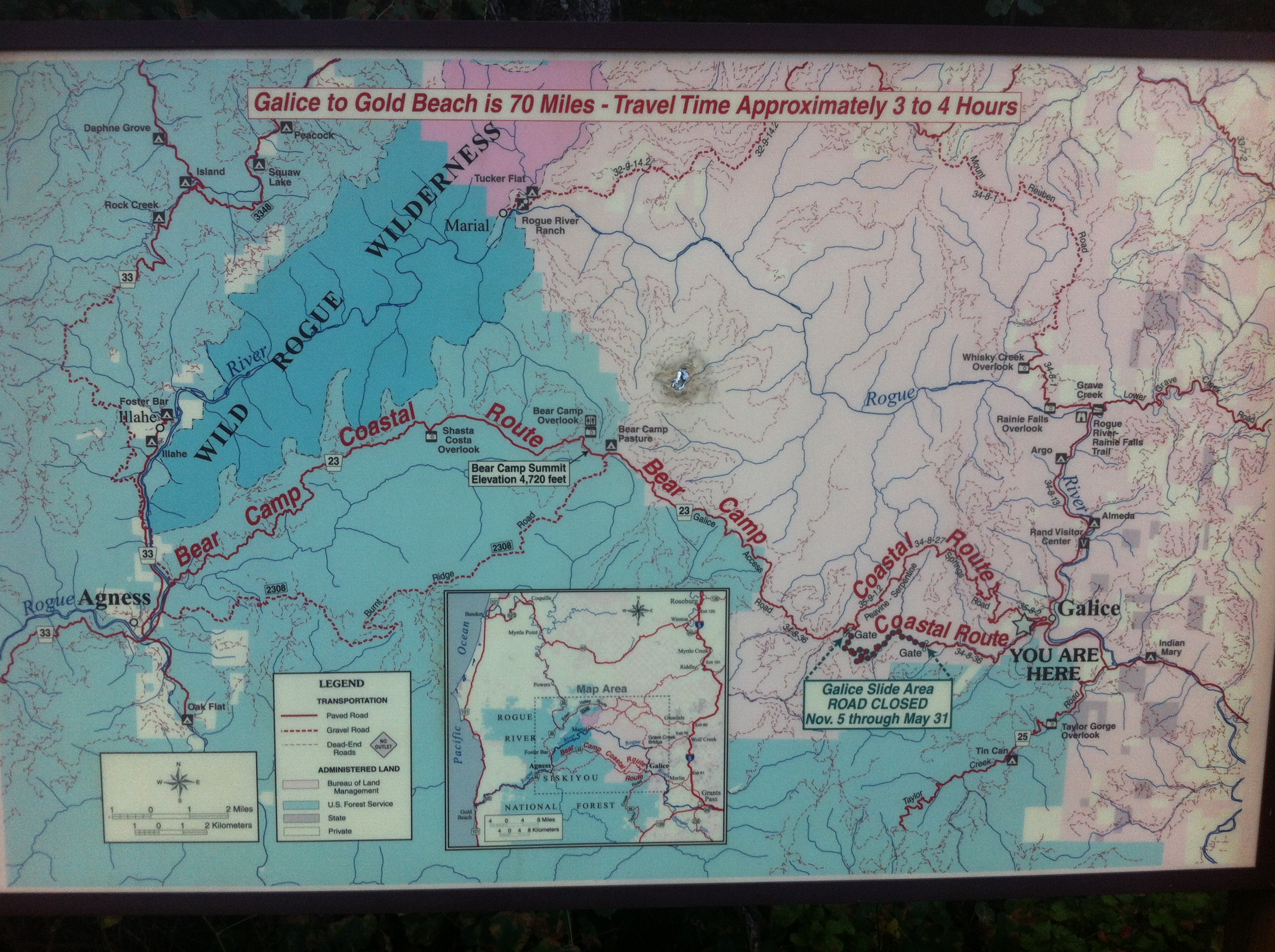

…but “turn about is fair play” indeed, and my father himself had some questionable lapses in judgement: like one epic trip coming back up over Bear Camp Road…

Soon enough dad’s bright yellow white-water drift boat was finished. After some initial test-drifts and setup, her true maiden voyage was an “all or nothing” trip down the infamous Grave Creek to Agness run, a 3 day (34 mile) trip through a mostly inaccessible stretch of the Wild and Scenic portion of the Rogue River. On this stretch of river there were only two points for (over-priced, first-come, first-serve) resupply: Paradise and Marial Lodges, and other than the rather primitive Rogue River hiking trail that ascends/descends along the right bank, these were the only points in or out of the canyon other than the river, or a Life-Flight. So, boaters heading down through this stretch of river needed to be self-sufficient, and pack for any eventuality. Comprising mostly Class II-IV rapids, it was certainly an enjoyable challenge for rafters of that era; but a drift boat is another thing entirely. Rafts could bounce and bump their way down through some of the tighter, trickier sections (such as Mule Creek Canyon, or Blossom Bar), but a drift boat has to be surgically guided in/around any and every obstacle or otherwise the oarsman risks swamping or overturning, so this initial run was done as ‘Spartan’ as possible -just a guide and his gear in each boat- in order for dad to more intimately learn the river and its moods. Once this initial “admission exam” was successfully completed, dad then started running his own independent trips, teaming up with Harley when the latter required an extra guide. After one such lower river run is when this particular story occurred: but if you will just bear with me a little longer, a bit more backstory is still needed.

In order to pick up a boat after a successful Wild and Scenic Rogue River trip, one generally did so at a small riverside town/boat-launch known as Agness. To get there, one could either “run the pavement” down Hwy 199 to the coast, turn N and continue up the Oregon Coastline on Hwy 101 to Gold Hill, turn East, and then work one’s way upstream to the goal: such a one-way trip would require most of an entire summer’s day. The preferred alternative was to come downriver (as if one were launching at Grave Creek) until just before the Galice store, turn up the “Bear Camp” road, and then work one’s way along this BLM/Forest Service logging road which followed the ridgeline running roughly parallel to the river-canyon. This route, even with its significantly slower speed, was a much faster option than it’s paved alternative, and so was the method of choice for most. It was a risky endeavor, however, and not just because of the potential for a breakdown in the middle of thousands of square miles of uninhabited, primitive area: it was also an active logging zone. It was quite common back then to encounter logging trucks on such roads; often “independents” working for Gyppo operations (AKA “paid by the load”) and so they were usually traveling at extremely high rates of speed, trying to maximize each day’s pay. And, due to the large, hurtling mass in question doing so on mixed dirt/gravel roads, they were all too dependent upon the laws of physics: at such speeds they couldn’t sufficiently slow down, and generally couldn’t even manage to get out of your way, especially if carrying a load. However, you could anticipate their behavior (and thus the potential consequence) if you were paying attention. For instance: going into the National Forest you would encounter slower, less maneuverable trucks under heavy load (highest danger), and coming out empty, more maneuverable trucks travelling at higher speed (high danger). Regardless, anyone who spent time on such “shared access roads” quickly learned to spot ahead for the tell-tail billowing clouds of dust that indicated potential doom hurtling toward oneself. Even today, decades later, one can still see the rusting, tragically twisted hulks of vehicles that found themselves (and their unfortunate occupants) at the bottom of the mountain’s flank after a desperate but ill-timed attempt to dodge such a catastrophe.

As I remember the trip in question (it is quite possible some of these early, formative memories have become somewhat jumbled) dad and Harley had again teamed up, each taking a shared load of passengers and gear. The plan was after the requisite 3-days for the trip had passed, my mom, brother and I were to meet dad around late-afternoon at the Agness launch, load up per usual the boat, gear, and client, and then head back up over the hill, hopefully getting back to Galice (a modest store/cafe/boat launch we habitually stopped at for a complimentary post-trip meal and refreshments) in the early evening before dropping the client off at their residence of choice. During those 3 days, however, mom had modified the plan, wanting to get us all out of the house so that we might enjoy the hot late-summer day swimming and exploring the cooler, coastal breeze-fed shoreline of the Lower Rogue Canyon. She had already packed the truck the night before and so we managed to leave bright and early on that fateful morning. We then cautiously made our way up and over Bear Camp, with my brother and I taking turns spotting the road ahead from the bed of the pickup in order to allow our mom the proper warning to find a safe pull-out so as to give Log trucks the “right of way” (realistically it was theirs, whether you granted it or not). From our turns at watch we had both noted that there was smoke coming from a ridge in the distance to the south, but we didn’t give it much thought, as spot fires were common that time of year, and we hadn’t heard any warnings or seen any road closure notices when we turned up the Bear Camp Road. Regardless, we successfully made it to the launch without incident, and after mom had expertly parked the truck/trailer, we spent most of the day frolicking along the cooler canyon-cradled riverside. Around the agreed upon time (like clockwork), we saw first one, then another of our party’s boats drifting down the broader coastal waterway to meet us. We welcomed them with enthusiastic waving before assisting in their “pulling ashore.” Refreshments were then passed around (as it was common for the last stretch of the trip to be as dry as the Prohibition, and so mom generally picked up a rack of Blitz -dad’s favorite- for the boaters), and the exited storytelling began to flow as per usual with the wetting of tongues. Times such as these are my greatest memories of early childhood: when I was still young and feral, my dad was an unfettered spirit, and the thought of tomorrow’s chores, or persistent hard times were but a faint memory. At times such as these, everyone’s mood was light, playful, and joyous.

Soon enough, afternoon approached evening, and still there was no sign of Harley’s ride. Even with a liberal dose of stress relief, it had become apparent to everyone something was wrong. A discussion began in earnest regarding what the best action might indeed be. We could all continue to wait at the launch of course; we could even spend the night if we had to, as we certainly had enough gear and would only have had to run into Gold Hill to replenish our food stock, but it wouldn’t help solve the mystery (and potential tragedy) of what might have happened to Harley’s “Old Lady.” Not to mention, dad had already taken extra time off work, and wasn’t entirely sure another unannounced absence would be very appreciated, especially in a time of high unemployment. So, an executive decision was finally made to unload the boats (usually the gear stayed in the boats for the ride home), stack one atop another upon the trailer, and then cram all of us (and the gear) into dad’s pickup to make the trip home where we hopefully wouldn’t come across the grisly remains of Harley’s truck and ex-life partner. It should perhaps be noted here some of the more specific details about this particular family pickup: it was a Ford “Custom Cab” (previously owned by Harley) sporting an “oh-so-70’s” candy apple yellow paint job with equally 70’s custom graphics. It also had a hot-rod small block V8 engine, and “three on the tree” transmission (I also remember some of these details originally relating to a dragster project dad had become involved in, so perhaps such facts are related). The resulting “Frankentruck” was probably the most least-likely trailer hauling solution anyone has ever conceived: it idled down the road at over 10 mph. Due to the ample horsepower on tap and little/no weight bias in the rear, pulling a boat up the ramp almost always resulted in a burnout (and you might imagine how much worse it was w/o a boat on the trailer). So it was a surprise to no one when the truck managed this much greater load without a complaint; if anything, in this overloaded state it was functioning better than ever!

With everyone crammed in and the gear packed expertly around us, we began the long trip back. Dad, “well lubricated” at this point, was both emboldened and desperate to make up for lost time. “Who knows what we might find on the road ahead? Best to get there while we still had some remaining daylight…” Up the twisting turning road we motored, dad’s leaden foot prompting us to mostly keep our heads down and hang on. I remember my brother and I sitting back against the tailgate pressed into place by the resulting g-forces, while mom sat with her back to the cab, desperately digging in her heels and grumbling under her breath at dad’s “Baja 1000” style driving tactics: for, dad wasn’t just going at a good clip, he was doing a trailer towing version of “drifting.” Hard acceleration down the straight (just the proper rate of speed to smooth out the speed ripples) hard on the brakes until committed to the slide, then into a 6 wheel drift, with the boats bouncing and banging noisily behind, all while feathering back into the throttle in order to rocket down the next straight. Looking back on the memory, it was proper Rally-Car technique, only with a vehicle packed to the sidewalls with bodies, boat gear, and with a double stack trailer following close in-tow. Everything that wasn’t tied or seat-belted down slid to the gravitational pull of each drift, and the outside corners often had one imagining nothing but sky under the related rear wheel. Inside the cab, dad could be heard whooping and joking with his boat mates while those of us delegated to the truck-bed were subjected to louder and louder protestations from mom. Coming at last up to the crest of the ridgeline, dad suddenly screeched to a full-lock stop at a pull out in midst a thick cloud of choking dust.

“WALT! What the hell do you think you are do-” and then we all turned to look at what dad was staring at as he slowly got out from behind the driver’s seat and the dust cleared: a couple miles down a generally straight track of road before us was an approaching wall of fire and smoke. Further beyond one could see the flashing lights of the yellow fire crew-trucks, and off in the distance you could see the big tanker planes lining up to drop their loads of retardant, all while helicopters upslope conducted spot-drops with water. “…well, sh#t.” dad muttered under his breath to no one in particular, and it was generally agreed that we had finally found the reason for the absence of the second truck and trailer. We then all stood transfixed for a spell, watching the scene: the big, lethargic tanker planes would line up for their approach, dropping their nose and gaining speed as they approached the ground. Then, at the last possible moment, the flaps would upturn, the nose would abruptly rise and the behemoth would groan reluctantly skyward again, dropping their reddish orange load in a broad arc ahead of the fast moving wildfire. The flames however, seemed undeterred, as they continued to leap and lick their way up slope through the dry underbrush. Further down slope one could see the conflagration crowning the canopy, creating mini fire tornadoes that spiraled skyward. When a Ponderosa Pine ignited, it was as if it literally exploded when the pitch-heavy wood caught. It was mesmerizing and fascinating for sure, but ultimately terrifying to witness the savage power of the blaze and its unrelenting march up the mountainside towards the narrowing path before us. In the meantime the adults discussed our options: “I think we could make it.” dad kept repeating amid the point/counterpoint over the policy at that time of enlisting able-bodies in the vicinity of a wildfire to help fight it (this was very common during lightning caused spot-fires near our home: the fire department would routinely go door to door for “volunteers” and few able-bodied adults felt they had the option to refuse) amid the loudly voiced displeasure regarding any of it from mom. Finally dad turned to us and stated firmly; “Alright, its getting late…get in.” knowing better than to argue, my brother and settled back in at the tailgate, mom resumed her ‘mirror’ of dad in the cab, and everyone else buckled in too. Dad started the truck, put it in gear, yelled “HANG ON!” and gunned it.

I think most of us had just assumed we were going to do something sane (like turn around and head back to Agness), but dad obviously had different ideas. No doubt concerned about being selected for fire duty after a trio of exhaustive days already, and knowing he would definitely be expected at work the next, his scales of judgement must have just…broke. We continued to accelerate. “KEEP YOUR HEADS DOWN!” he yelled out the window as I began to hear a steadily rising sound akin to a banshee wail emanating from my mother: “WAAAAAALT!” As we quickly approached the fire zone, you could feel the air increase in temperature: have you ever opened a woodstove when its at “full stoke” and felt that near shriveling heat on your skin, in your throat and on the back of your eyeballs"? That’s precisely how the air felt. The truck was going so fast at this point its as if it had floated off the ground (the trailer too). We also seemed to be in a weird gravity-free stasis; everything slowed down as if in slow-motion. This was the first time I can remember feeling this now all-too-familiar state. It later became a common experience for me once I started riding and racing motorcycles, and served me well during my arborist/tree climber days. It tends to happen at times of high stress: when one is in the middle of an accident, near accident, or other moments which prompt extremely high adrenaline.

At a seeming snail’s pace I raised my head up just in time to see us entering what now appeared to be an ever growing tunnel of smoke. Equally slowly, I laid my head back down and looked up as the sky became streaked in grey umber. The color deepened to a solid background of rolling charcoal grey, dark umber and black, accentuated by a back-light of deep red. I watched, fascinated, as tongues of flame gracefully danced over the truck…it was so awe inspiring (thankfully), that one couldn’t help but hold ones breath. These tongues slowly transformed into a sheet, and then a wave, and as if in a slow motion dream-state it seemed we now surfed along this fiery face, advancing ever closer to its inevitable embrace…then the sky suddenly turned a vivid blue, and the wind, dust and noise were upon us again. I could smell the acrid stench of smoldering hair, paint and nylon.

I could also hear my mother again, uttering a string of curses at my father that should have crippled him and turned his hair grey on the spot. Instead, war whoops and shouts of victory drowned her voice from within the cab. It seems for those riding encased safely in a cocoon of glass and steel, it had been quite a treat: “Icing on the cake” for a trip already filled with lifetime bucket-list moments. Once well past the danger zone, dad parked upon a distant pullout that allowed a broader view of the action occurring in our wake. The hillside, and most alarmingly the road we had just traveled, was now completely engulfed in flame. Soon after, the fire had crested the ridge and continued on to who knows where. By then mom had become quite silent, seething as hotly as the trial we had just endured, and would keep such embers stoked until a rather personal conversation between her and her husband later. We lingered there until the declining sun and the threat of being caught up on the mountainside in an active fire zone became a voiced concern again (the dusty trails of yellow fire vehicles were spotted on some nearby roads moving fast towards us; for what purpose exactly, will forever remain a mystery). So prompted, we all quickly piled back into the truck, and headed for Galice.

Once at the cafe, we all ate a hearty meal, and the adults indulged in their favorite spirit. Since Galice didn’t remain open late back then even on weekends, we all ended up getting home at a reasonable hour, even with the added round trip of having to drop Harley off (we would have only been 1/2 way home via the coastal route at that point). Mom either saved her coveted ember for a later time, or the conversation was very short and of the type that quickly degenerates to “ultimatum.” Dad was well familiar with these, and so already knew the most sensible tact. Regardless, whatever transpired between them wasn’t loud enough to wake my brother and I, sleeping within earshot.

And what of Harley’s missing significant? Was she smote down from on high? Was she consumed utterly within the fiery embrace of Hephaestus? Did she foresee Armageddon and humbly retreat before its unstoppable advance? No. Come to find out, early in her ascent up the mountain she had pulled off the road to let a log truck pass by and had gotten the trailer stuck. So, she simply unhooked the trailer, and headed back to civilization. This was not an altogether uncommon problem on that road: there was many a trip where we came across orphaned trailers balanced precariously on the roadside, and/or others parked upon deflated tires in a pull out. However, instead of going for help, flagging down a truck to use their CB, finding a payphone, or something else semi-sensible, she just drove the 80 miles back home, parked the truck and just figured everything would work out “OK” for us…

…however, I’m not entirely sure it was OK for her once Harley returned home and heard her side of the story that night…?

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.