China has one of the largest populations in the world, which means that they have one of the fastest-growing elderly population. According to a United Nations population report, China’s population of elderly is expected to grow 71% between 2015 and 2030.[1] This presents a significant problem for the Chinese government, who must house and care for its current population of 1.3 billion. China has experienced a massive industrial and societal shift as the culture and economy have focused more on urbanization and industrialization, and less on traditional values and practices.

Filial piety or xiào (孝) is a tenant of Confucianism that has been practiced in China for over 2500 years.[2] An excellent article by Aris Teon in the Greater China Journal breaks down the cultural and historical complexities and the importance of this idea. In essence, it mandates that for all the parents have given their children—life, a home, education—the child owes the parent an eternal debt that can only be partially repaid by caring for their parents in their old age.[3] This philosophy extends beyond mere care for elders and dictates specific ways children should be subservient to their parents—to strive to improve the state and serve the ruler. Summarizing the extent to which this philosophy is practiced, the following quote comes from a paper that analyzed the state of elder care in China.

“The concept of xiào went beyond simply taking care of elderly parents; it clearly defined children’s attitudes and behaviors within a family. Children were expected to be submissive by following parents’ every decision. Filial piety began with service and obedience to parents, continued with total devotion to their welfare, and extended with loyalty to rulers and authorities in the society. Xiào was considered the basis of family and social order.”[4]

An example of younger generations paying respect to their elders, exemplifying filial piety. Image was included in Illustrations of the Classic of Filial Piety, by an unknown author, possibly Ma Hezhi (fl. 1131-1189) as painter and Emperor Gaozong (1107-1187) as calligrapher, during the Song dynasty (960-1279).[5]

The extreme adherence to this idea can be exemplified in Number 13 of The Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars*, *a set of twenty-four tales that exemplify the xiào between a child and their parents, written by Guo Jujing (郭居敬) during the Yuan dynasty (1260–1368).[6]

“13. HE BURIED HIS SON FOR HIS MOTHER (Guō Jù) (Wèi Mǔ Mái Ér) In the Hàn dynasty the family of Guō Jù was poor. He had a three-year-old son. His mother sometimes divided her food with the child. Jù said to his wife: “[Because we are] very poor, we cannot provide for Mother. Our son is sharing Mother’s food. Why not bury this son?” He was digging the pit three feet deep when he struck a cauldron of gold. On it [an inscription] read: “No official may take this nor may any other person seize it.”

A verse says of him: “Guō Jù wishes to serve his mother, and Buries his son that his mother may survive; Yellow gold is bestowed by heaven, and Brilliant fortune brightens their poor threshold.”

A depiction of the 13th tale.[7]

This philosophy is still practiced in mainland China and plays a significant role in shaping family dynamics and hierarchy, as well as care of elders. This idea of obligation to one's parents and society as a whole means that a child’s first duty is towards their parents, and lastly to themselves. To disdain these ideas can result is vicious exclusion and exile from the community. Conversely, being perceived as a paragon of xiào condones great respect upon the individual, family, and community. This is exemplified in The Oil Vendor and the Queen of Flowers, a classic of Chinese literature.

“Shilao was seriously ill, and soon he died. Zhu Zhong [Shilao’s adoptive son] mourned him as if he had been his own flesh and blood, and buried him according to the appropriate customs and rites so that the whole neighborhood praised his moral virtues as a filial son. After carrying out his filial duties, Qin Zhong reopened the oil shop.”[8]

This philosophy is being directly challenged due to a massive shift in demographics with children living in cities or far from parents; elders can no longer rely on tradition and their children to care for them. Before, it was traditional for three—or sometimes four generations to all—live in the same house. Young men would seek to get married, then move in with their parents who could care for their children. In turn, the children would care for the parents or grandparents as they aged, providing them with dignity and respect until the end of life. It was expected that if your parents cared for you when you were young and helpless, you should care for them when they are old and helpless. Now young men travel to cities to pursue work, leaving their parents and grandparents in impoverished villages to fend for themselves.

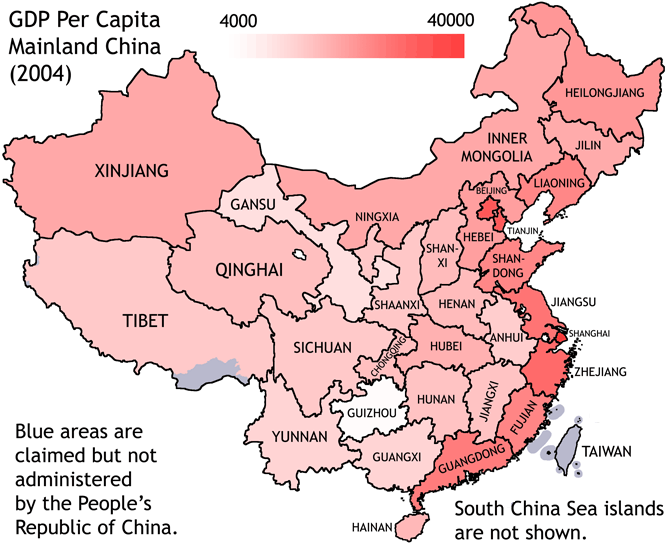

A diagram of GDP in 2004 per region, the wealthiest places run east to west indicating more industry, jobs, and higher population in urban areas.[9]

In addition to job centralization in cities and the depopulation of the countryside, the one-child policy (implemented initially to combat an uncontrolled population increase) has produced the 4:2:1 problem. Namely the fact that there are four grandparents and two parents all relying on the support of one working child—usually a male[10]. The preference for males during the Policies Height led to sixteen males being born for every one female.[11] This has led to millions of bachelors with little hope of marriage.

As there are fewer jobs and inadequate food supplies in rural areas, there has been a horrifying increase in elder abandonment and abuse. In places where the jobs have moved to the cities and the children follow them for work, elders who cannot work are seen as a burden. High in the mountains of the Fujian province, a Buddhist temple, called the Ji Xiang temple, serves as a home for elders that have been abandoned by their families and shunned by their communities. The temple’s 84-year-old head nun Neng Qing tells a heartbreaking story of how elders are cast out from their homes and rejected by communities.

“In a neighboring village, there was one old person who had eight children. Every morning, he went to each of the children's families, but no-one even invited him in for breakfast. The village contacted us, but it was too late. He had already committed suicide.”[12]

The Ji Xing temple is one of the few places providing free end of life care; the government is struggling to provide the rest. The current state of elder care in China is precarious. According to the China Business Review, only about 1.6% of all seniors are funded—a full 6.4% below the world bank’s standard.[13] These numbers can be interpreted as “a need for an additional 3.4 million hospital and nursing home beds dedicated to senior care over the next five years alone.”[14]

All these factors make professional care for the elderly imperative. The Chinese government does not currently have any regulations about the standards of care for the elderly nor any accrediting agency for private companies seeking to provide those services. The central government prefers to reimburse citizens for in-house care by trained professionals, rather than establish care facilities. Not only is this in line with cultural values about how elders should be attended and treated, but it is believed to be more cost effective.[15] Additionally, the Ministry of Health stated that “China plans to develop the smart health and elderly care industry in the next four years to grant universal access to health management services and home-based elderly care.”[16] The ministry also aims to build a coalition of providers to establish a diverse and responsive industry within the next four years.[17] Finally, the ministry seeks to integrate technology in the form of big data analysis, wearable technology, and potentially home-service robots.

An example of elders playing a game.[18]

In reality, the need for a geriatric industry and infrastructure of professional elder care is inevitable and unavoidable; and the public and private sectors are rushing to meet demand. Both government-owned homes and community-owned homes exist. The former is funded and staffed by the national and local government; the latter must pay rent and utilities, and generate enough income to pay staff and provide services. Both types accept donations from public and private sources, and several private homes are repurposed government homes. These facilities differ in many ways, one of the most obvious being size and capacity. Government homes, in general, have been around longer, are larger, and provide a wider variety of services. Private homes are smaller but more specialized. Additionally, government homes are usually better staffed and their staff receives a higher salary.[19] Finally, some facilities are covered under universal health insurance, either reimbursing the patient for care given or covering costs directly. If a facility is not covered, then all expenses must be paid out of pocket. Furthermore, it is essential to note that the geriatric industry is in its infancy. Between one half and two-thirds of all care facilities in Nanjing were founded in the last decade, with most staff being minimally trained migrant workers.[20] Beijing, one of the largest cities in China, has two hundred and fifteen public nursing homes and one hundred and eighty-six private homes, or roughly three beds for every hundred seniors.[21] According to the Beijing evening news, there are ten thousand applicants waiting for the eleven hundred beds on offer in the capital's top government home.[22]

In addition to specialized homes and facilities, domestic helpers can play a crucial role in elder care. These are individuals who come to a community of elders and assist them with daily tasks. While home-based care still accounts for nearly 85% of all elder care, domestic helpers assist in making such care viable for the immediate future.[23]

Most helpers are between thirty and fifty years old, with over 70% of these helpers possessing less than a high school education. The income of foreign domestic workers tends to be higher than local Chinese domestic helpers.[24] The helper's work can be demanding, especially when dealing with highly dependent adults; some are made to do menial tasks like cleaning and other housework in addition to their duties as a caretaker. High workload and low pay can lead to a high turnover rate which causes concerns for both workers and employers. Additionally, workers are not protected under Chinese labor laws and few sign contracts with their employers, leaving them open to exploitation and abuse. Migrant workers may find it difficult to adapt to a new country due to difficulties with its language and customs, which can make a demanding job even harder. Finally, most workers are undertrained, while there is a government-issued certificate for domestic helpers, only 6% of domestic helpers earned the certificate before employment.[25] Textbooks have been published, but the literacy rates amongst helpers—especially rural migratory helpers—make them of limited use. While classes and specific courses are offered in some areas, most workers cannot afford the time or the money to take them. In short, there is a myriad of problems with migratory domestic helpers and no easy solution.

In light of modern challenges, the reshaping of xiào is complicated and controversial. In 1996, the Chinese government passed the Protection of the Rights and Interests of Elderly People, also known as the Filial Piety Law, in response to the rising rates of elder abandonment in rural areas and the systemic neglect and abuse in poorly-regulated, newly constructed care facilities. The law states that “Discriminating against, insulting, maltreating or forsaking the elderly is forbidden.”[26] The law mandates that “supporters” and their spouses are required to pay medical expenses, “cater to [their elder’s] special needs,” cook for and feed them, farm their land, and refrain from assigning them to work beyond their ability.[27] Supporters are defined as “the sons and daughters of the elderly and other people who are under the legal obligation to provide for the elderly.”[28] The law also includes provisions to punish insulting the elderly either verbally or physically, stealing from or extorting the elderly, or failing to fulfill the piety duties as mandated by the state and customs.[29] Punishments can range from having one’s name publicly called out to having their credit negatively affected, which could prevent them from buying a house, founding a business, or registering for a library card.[30]

In 2012, the law was revised to include the creation of a social security system to gradually improve social and financial security for the elderly. It also employed scientific research and it established a statistical system that would release information to better improve strategies towards elder care.[31] The revision further mandated that supporters must not only respect and tend to their parents, but that they must also “frequently visit or greet the elderly. Employers shall, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the state, ensure the rights of the supporters to have the family visit leave.”[32] The revision permitted care to be handed over to a third party, provided the elder consented. “If they cannot take care of the elderly in person, they may, according to the will of the elderly, commission other individuals or institutions for the elderly to take care of the elderly.”[33] Finally, it was mandated that a positive image of elders and elder care be taught and reinforced in schools and through the media.

“The publicity and education on respecting, providing for and helping the elderly shall be extensively carried out throughout the country to establish the social values under which the elderly are respected, cared for and helped. The organizations of juveniles, schools, and kindergartens shall carry out moral education on respecting, providing for and helping the elderly and education in the legal system on protecting the lawful rights and interests of the elderly among young people and children.

Radio programs, films, television programs, newspapers and periodicals, internet and so on shall serve the elderly by reflecting the life of the elderly and carrying out publicity on protecting the lawful rights and interests of the elderly.”[34]

The law was met with mixed reactions. Dang Janwu, Vice Director of the China Research Center on Aging, stated that “The social welfare system can answer the material needs of elders, but not the spiritual needs.”[35] Outside of a strictly legal setting, however reinterpretations of xiào have been more harmonious in some urban settings as the realities of the situation have set in. Dr. Feng was a Chinese-American who conducted outstanding research on growing populations of minorities in American nursing homes; he remarked upon his return to China in 2006, “You’d imagine elders would be upset, but they tell you ‘I’d rather live by myself. I’m pretty happy here. I can chat with people…instead of spending every day with my son’s family.”[36] A qualitative study conducted in Nanjing City, Zhan, Luo, and Feng found that elders in urban environments had broadened their concept of xiào. They understood that their children could not care for them due to obligations of family, work, and children; but they interpreted their children’s ability to pay for expensive elder care as amounting to the same adherence of xiào as if they had personally attended by their parents.[37]

Elder care in China is a complex and controversial topic. Ancient traditions require a system of care that is no longer practical in light of modern economic and social factors like industrialization and job migration. Care then falls either to the family who (if they are wealthy enough to afford one) can hire a migrant helper to assist in their care. If the family is fortunate enough to be near a city and has enough money, they can enroll their elder in a specialized facility. At worst, families and communities simply abandon elders to fend for themselves. The government is rushing to address these problems by constructing more facilities and passing laws to uphold the moral integrity of its citizens.

Works Cited

“Aging China: Changes and Challenges.” BBC News, September 19, 2012. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-19630110.

artist, Unknown. Illustrations of the Classic of Filial Piety. Song dynasty ( -1279 960. Ink and colors on silk, album leaf. National Palace Museum. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Classic_of_Filial_Piety_(%E5%A3%AB%E7%AB%A0_%E7%95%AB).jpg.

“China Plans Smart Health and Elderly Care.” Accessed January 30, 2018. http://en.nhfpc.gov.cn/2017-02/17/c_72766.htm.

“China’s Ageing Population: 100-Year Waiting List for Beijing Nursing Home - Telegraph.” Accessed February 24, 2018. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/china/9805834/Chinas-ageing-population-100-year-waiting-list-for-Beijing-nursing-home.html.

Dingar. English: The Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars - No. 24. [object HTMLTableCellElement]. Own work. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%E4%B8%BA%E6%AF%8D%E5%9F%8B%E5%84%BF.JPG.

“Domestic Helpers as Frontline Workers in China’s Home-Based Elder Care: A Systematic Review.” Accessed February 24, 2018. http://www.tandfonline.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/doi/pdf/10.1080/08952841.2016.1187536?needAccess=true.

Dong, XinQi. “Elder Rights in China: Care for Your Parents or Suffer Public Shaming and Desecrate Your Credit Scores.” JAMA Internal Medicine 176, no. 10 (October 1, 2016): 1429–30. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5011.

Endrjuch. English: Xiangqi Chess. March 26, 2010. Own work. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Xiangqi-Chinese-chess.jpg.

Feng, Zhanlian, Heying Jenny Zhan, Xiaotian Feng, Chang Liu, Mingyue Sun, and Vincent Mor. “An Industry in the Making: The Emergence of Institutional Elder Care in Urban China.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 59, no. 4 (April 2011): 738–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03330.x.

“File:GDP per Capita China 2004.Png.” Wikipedia, April 5, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:GDP_per_capita_China_2004.png&oldid=774041602.

Hatton, Celia. “Who Will Take Care of China’s Elderly People?” BBC News, December 21, 2015, sec. Magazine. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35155548.

“Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly -- China.Org.Cn.” Accessed February 23, 2018. http://www.china.org.cn/english/government/207403.htm.

“Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly (2012 Revision).” Accessed February 23, 2018. http://www.lawinfochina.com/display.aspx?id=12566&lib=law.

“New Law Requires Adult Children to ‘Visit Home Often’ - All China Women’s Federation.” Accessed February 24, 2018. http://www.womenofchina.cn/womenofchina/html1/news/china/15/3869-1.htm.

Parkinson, Justin. “Five Numbers That Sum up China’s One-Child Policy.” BBC News, October 29, 2015, sec. Magazine. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-34666440.

“Placing Elderly Parents in Institutions in Urban China A Reinterpretation of Filial Piety.” Accessed February 23, 2018. http://journals.sagepub.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/doi/pdf/10.1177/0164027508319471.

“Recent Developments in Institutional Elder Care in China.” Accessed February 24, 2018. http://www.tandfonline.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/doi/pdf/10.1300/J031v18n02_06?needAccess=true.

“Senior Care in China: Challenges and Opportunities – China Business Review.” Accessed January 30, 2018. https://www.chinabusinessreview.com/senior-care-in-china-challenges-and-opportunities/.

Span, Paula. “In China, a More Western Approach to Elder Care.” The New Old Age Blog, 1311787337. //newoldage.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/07/27/in-china-a-more-western-approach-to-elder-care/.

Teon, Aris. “Filial Piety (孝) in Chinese Culture.” The Greater China Journal (blog), March 14, 2016. https://china-journal.org/2016/03/14/filial-piety-in-chinese-culture/.

“The Impact of Rural-Urban Migration on Familial Elder Care in Rural China.” Accessed February 23, 2018. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1037&context=sociology_diss.

“THE TWENTY-FOUR FILIAL EXEMPLARS.” Accessed February 23, 2018. http://pages.ucsd.edu/~dkjordan/chin/shiaw/FilialExemplarsEnglish.pdf.

Wong, Edward. “A Chinese Virtue Is Now the Law.” The New York Times, July 2, 2013, sec. Asia Pacific. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/03/world/asia/filial-piety-once-a-virtue-in-china-is-now-the-law.html.

“WPA2015_Report.Pdf.” Accessed January 30, 2018. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Report.pdf.

“WPA2015_Report.Pdf.”

Teon, “Filial Piety (孝) in Chinese Culture.”

Teon.

“The Impact of Rural-Urban Migration on Familial Elder Care in Rural China.”

artist, Illustrations of the Classic of Filial Piety.

“THE TWENTY-FOUR FILIAL EXEMPLARS.”

Dingar, English.

Teon, “Filial Piety (孝) in Chinese Culture.”

“File.”

“Ageing China.”

Parkinson, “Five Numbers That Sum up China’s One-Child Policy.”

Hatton, “Who Will Take Care of China’s Elderly People?”

“Senior Care in China.”

“Senior Care in China.”

“Senior Care in China.”

“China Plans Smart Health and Elderly Care.”

“China Plans Smart Health and Elderly Care.”

Endrjuch, English.

“Recent Developments in Institutional Elder Care in China.”

Feng et al., “An Industry in the Making.”

“China’s Ageing Population: 100-Year Waiting List for Beijing Nursing Home - Telegraph.”

“China’s Ageing Population: 100-Year Waiting List for Beijing Nursing Home - Telegraph.”

“Domestic Helpers as Frontline Workers in China’s Home-Based Elder Care: A Systematic Review.”

“Domestic Helpers as Frontline Workers in China’s Home-Based Elder Care: A Systematic Review.”

“Domestic Helpers as Frontline Workers in China’s Home-Based Elder Care: A Systematic Review.”

“Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly -- China.Org.Cn.”

“Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly -- China.Org.Cn.”

“Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly -- China.Org.Cn.”

“Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly -- China.Org.Cn.”

Dong, “Elder Rights in China.”

“Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly (2012 Revision).”

“Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly (2012 Revision).”

“Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly (2012 Revision).”

“Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly (2012 Revision).”

Wong, “A Chinese Virtue Is Now the Law.”

Span, “In China, a More Western Approach to Elder Care.”

“Placing Elderly Parents in Institutions in Urban China A Reinterpretation of Filial Piety.”

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.