Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Myths & Legends of Babylonia & Assyria by Lewis Spence, 1916.

Taboo

The belief in taboo was universal in ancient Chaldea. Amongst the Babylonians it was known as mamit. There were taboos on many things, but especially upon corpses and uncleanness of all kinds. We find the taboo generally alluded to in a text "as the barrier that none can pass."

Among all barbarous peoples the taboo is usually intended to hedge in the sacred thing from the profane person or the common people, but it may also be employed for sanitary reasons. Thus the flesh of certain animals, such as the pig, may not be eaten in hot countries. Food must not be prepared by those who are in the slightest degree suspected of uncleanness, and these laws are usually of the most rigorous character; but should a man violate the taboo placed upon certain foods, then he himself often became taboo. No one might have any intercourse with him. He was left to his own devices, and, in short, became a sort of pariah.

In the Assyrian texts we find many instances of this kind of taboo, and numerous were the supplications that these might be removed. If one drank water from an unclean cup he had violated a taboo. Like the Arab he might not "lick the platter clean." If he were taboo he might not touch another man, he might not converse with him, he might not pray to the gods, he might not even be interceded for by anyone else. In fact he was excommunicate. If a man cast his eye upon water which another person had washed his hands in, or if he came into contact with a person who had not yet performed his ablutions, he became unclean. An entire purification ritual was incumbent on any Assyrian who touched or even looked upon a dead man.

It may be asked, wherefore was this elaborate cleanliness essential to avoid taboo? The answer undoubtedly is—because of the belief in the power of sympathetic magic. Did one come into contact with a person who was in any way unclean, or with a corpse or other unpleasant object, he was supposed to come within the radius of the evil which emanated from it.

Popular Superstitions

The superstition that the evil-eye of a witch or a wizard might bring blight upon an individual or community was as persistent in Chaldea as elsewhere. Incantations frequently allude to it as among the causes of sickness, and exorcisms were duly directed against it. Even to-day, on the site of the ruins of Babylon children are protected against it by fastening small blue objects to their headgear.

Just as mould from a grave was supposed by the witches of the Middle Ages to be particularly efficacious in magic, so was the dust of the temple supposed to possess hidden virtue in Assyria. If one pared one's nails or cut one's hair it was considered necessary to bury them lest a sorcerer should discover them and use them against their late owner; for a sorcery performed upon a part was by the law of sympathetic magic thought to reflect upon the whole. A like superstition attached to the discarded clothing of people, for among barbarian or uncultured folk the apparel is regarded as part and parcel of the man.

Even in our own time simple and uneducated people tear a piece from their garments and hang it as an offering on the bushes around any of the numerous healing wells in the country that they may have journeyed to. This is a survival of the custom of sacrificing the part for the whole.

If one desired to get rid of a headache one had to take the hair of a young kid and give it to a wise woman, who would "spin it on the right side and double it on the left," then it was to be bound into fourteen knots and the incantation of Ea pronounced upon it, after which it was to be bound round the head and neck of the sick man. For defects in eyesight the Assyrians wove black and white threads or hairs together, muttering incantations the while, and these were placed upon the eyes. It was thought, too, that the tongues of evil spirits or sorcerers could be 'bound,' and that a net because of its many knots was efficacious in keeping evilly-disposed magicians away.

Omens

Divination as practised by means of augury was a rite of the first importance among the Babylonians and Assyrians. This was absolutely distinct from divination by astrology. The favourite method of augury among the Chaldeans of old was that by examination of the liver of a slaughtered animal. It was thought that when an animal was offered up in sacrifice to a god that the deity identified himself for the time being with that animal, and that the beast thus afforded a means of indicating the wishes of the god.

Now among people in a primitive state of culture the soul is almost invariably supposed to reside in the liver instead of in the heart or brain. More blood is secreted by the liver than by any other organ in the body, and upon the opening of a carcase it appears the most striking, the most central, and the most sanguinary of the vital parts. The liver was, in fact, supposed by early peoples to be the fountain of the blood supply and therefore of life itself. Hepatoscopy or divination from the liver was undertaken by the Chaldeans for the purpose of determining what the gods had in mind. The soul of the animal became for the nonce the soul of the god, therefore if the signs of the liver of the sacrificed animal could be read the mind of the god became clear, and his intentions regarding the future were known.

The animal usually sacrificed was a sheep, the liver of which animal is most complicated in appearance. The two lower lobes are sharply divided from one another and are separated from the upper by a narrow depression, and the whole surface is covered with markings and fissures, lines and curves which give it much the appearance of a map on which roads and valleys are outlined. This applies to the freshly excised liver only, and these markings are never the same in any two livers.

Certain priests were set apart for the practice of liver-reading, and these were exceedingly expert, being able to decipher the hepatoscopic signs with great skill. They first examined the gall-bladder, which might be reduced or swollen. They inferred various circumstances from the several ducts and the shapes and sizes of the lobes and their appendices. Diseases of the liver, too, particularly common among sheep in all countries, were even more frequent among these animals in the marshy portions of the Euphrates Valley.

The literature connected with this species of augury is very extensive, and Assur-bani-pal's library contained thousands of fragments describing the omens deduced from the practice. These enumerate the chief appearances of the liver, as the shade of the colour of the gall, the length of the ducts, and so forth. The lobes were divided into sections, lower, medial, and higher, and the interpretation varied from the phenomena therein observed. The markings on the liver possessed various names, such as 'palaces,' ‘weapons,' 'paths,' and 'feet,' which terms remind us somewhat of the bizarre nomenclature of astrology. Later in the progress of the art the various combinations of signs came to be known so well, and there were so many cuneiform

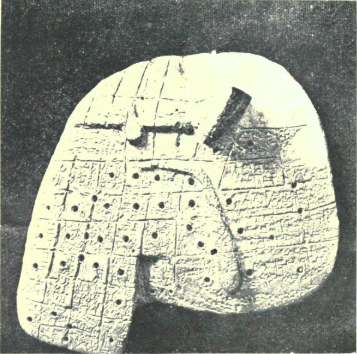

This is inscribed with magical formula; it was probably used for purposes of divination, and was employed by the priests of Babylon in their ceremonies texts in existence which afforded instruction in them, that a liver could be quickly ‘read' by the baru or reader, a name which was afterward applied to the astrologists as well and to those who divined through various other natural phenomena.

One of the earliest instances on record of hepatoscopy is that regarding Naram-Sin, who consulted a sheep's liver before declaring war. The great Sargon did likewise, and we find Gudea applying to his 'liver inspectors' when attempting to discover a favourable time for laying the foundations of the temple of Nin-girsu. Throughout the whole history of the Babylonian monarchy in fact, from its early beginnings to its end, we find this system in vogue. Whether it was in force in Sumerian times we have no means of knowing, but there is every likelihood that such was the case.

Spence, Lewis. Myths & Legends of Babylonia & Assyria. George G. Harrap & Co., 1916.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.