Korean Folklore and Literacy

For centuries, the literature of Korea was divided by the literacy of its people. For the most part, only members of the yangban nobility learned to read and write. They studied Chinese characters until the creation of Hangul, the Korean alphabet, in 1446. Its inventor, King Sejong the Great, intended to open knowledge to the lower classes. Hangul became the official script of Joseon Korea in 1894. Before then, it was mostly used by noble women.[1]

Hangul's new prominence improved literacy rates in the early 20th century. But peasant families possessed their own literary traditions told through stories, songs, and plays. Their oral culture passed on folk ceremonies, legends, ballads, and medicine for thousands of years. Perhaps the most famous form of Korean storytelling is p'ansori, a folktale duet between singer and drummer.[2]

Korean Folk Plays and Satire

Masked plays, or talchun, have been performed in Korea since at least the 9th century. They likely began much earlier as rites in shamanic kut ceremonies. Actors played out the dramas through music and dance in a variety of styles. Folk plays in the Joseon dynasty often satirized the yangban nobles as a form of social commentary. They gave individual people a way to express their emotions, both positive and negative, in a safe environment. Wandering dancers traveled between villages to perform for eager audiences.[2][3]

Printing and Record-Keeping in Korea

While the commoners made fun of the elites, Korea was developing into a complex political state. The dynasties of the Three Kingdoms drafted its first official records, though few have survived to the present day. Each kingdom kept its own histories, which they valued as gifts to future generations. Goguryeo and Baekje published their first histories by the 4th century CE. Silla's oldest known historical works date to the 6th.[4]

Korea's culture of careful record-keeping benefitted from the movable-type printing press. The invention spread from China to Unified Silla in the 8th century. By the Goryeo period, Korean printing was widely known for its quality. Its oldest surviving histories come from this era. This includes the oldest of all, the History of the Three Kingdoms, published in 1145. Goryeo also produced the Tripitaka Koreana between 1236 and 1251. Printed on more than 80,000 woodblocks, or roughly 160,000 pages, the Tripitaka is still stored at Haeinsa Temple in South Korea.[4][5]

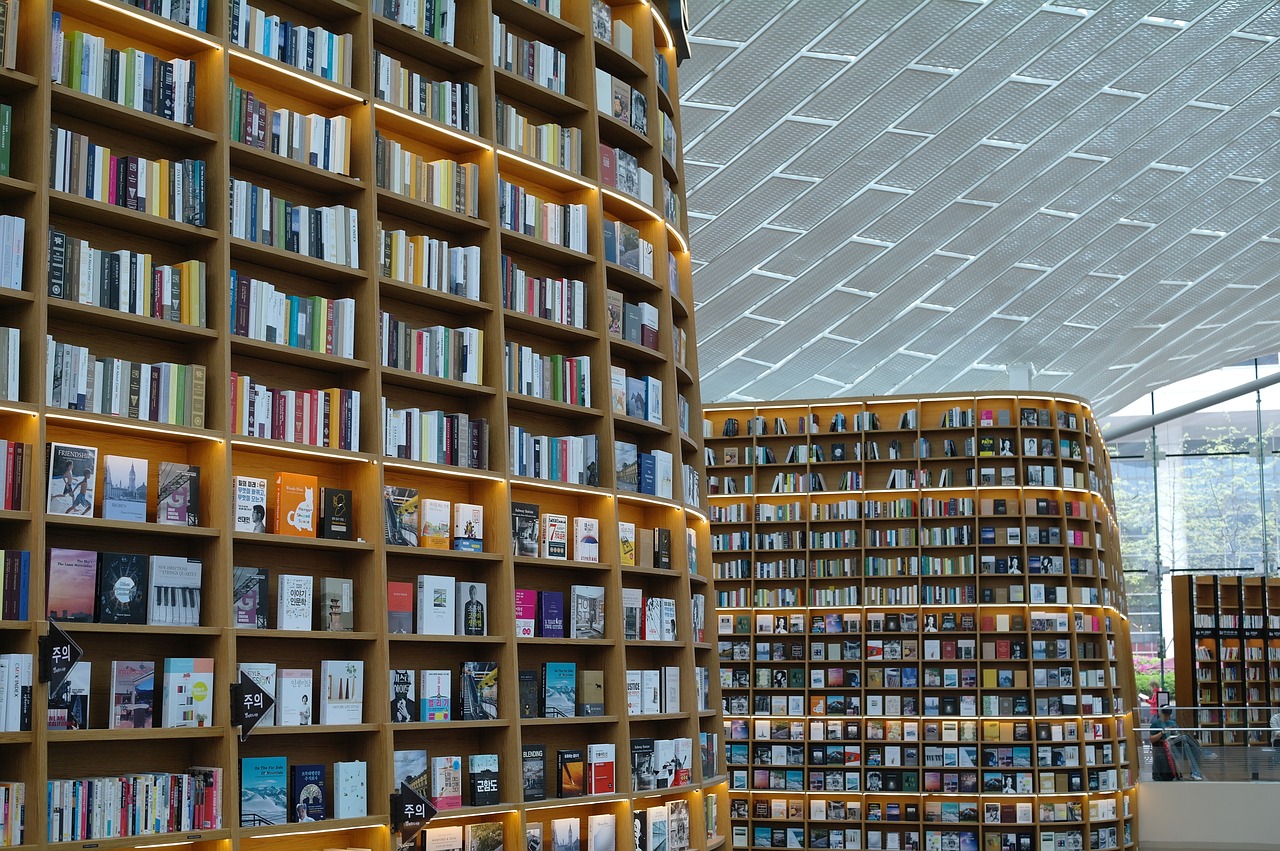

In 1234, Korea developed the world's first metal movable type printing press. This invention fed the libraries of the Joseon dynasty, whose ruling class gained power through education. In 1392, one of the last acts of the Goryeo dynasty, the National Office for Book Publication was established. Scholar-kings like Sejong the Great commissioned vast collections of works in medicine, philosophy, history, and poetry.[5][6] In later Joseon, court women also published books of poetry, essays, and memoirs about their lives in the court.[2]

Modern Korean Literature

New voices emerged in the wake of the turbulent 20th century. While North Korea remains insular, South Korea has embraced the wider world through business, art, and literature. Common themes in modern Korean literature explore the consequences of war, the strain of modernization, and stories of the diaspora. Other forms of storytelling, notably Korean television dramas, have met global success. Many Korean dramas depict stories from its history. In this way, they bring the works of its ancient writers to new generations.[7]

Bibliography

Douglas Biber, Dimensions of Register Variation: A Cross-Linguistic Comparison (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006), 44.

Michael J. Seth, A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2011), 216-222.

Cho Dong-il, Korean Mask Dance, trans. Lee Kyong-hee, vol. 10 (Seoul: Ewha Womans University Press, 2005).

Stella Xu, Reconstructing Ancient Korean History: The Formation of Korean-ness in the Shadow of History (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2016).

Insup Taylor and M. Martin Taylor, Writing and Literacy in Chinese, Korean and Japanese (Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins, 2014), 95-100.

Seth, 118-120.

Abby Addao, "Tracing The History Of Korea - Through The Best Korean Historical Dramas," Hellokpop, May 18, 2017, Hellokpop.com, accessed May 22, 2017.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.