From “Jiu-Jitsu, As Seen by William E. Curtis” in A Complete Course of Jiu-Jitsu and Physical Culture by William E. Curtis and John J. O'Brien, 1905.

Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

One of the chief reasons for the success of the Japanese in battle, for their nerve and endurance, tor the remarkable physical vigor of the nation, for the low death-rate, and their material progress, may be found in the athletic exercises which are required of every child and are continued through life by a large proportion of the population.

Jiu-jitsu, the noble science of self-defense ("the gentle art," to translate the word literally), may be called the national sport, and has been of incalculable advantage to Japan. Everybody, from the emperor down to the humblest coolie, is educated in it, and, as in everything else, there are those who excel. It is as much a part of the education of a soldier as the handling of a gun. No man can obtain a place on the police force until he is proficient in it, and if the same requirement were made in the United States the efficiency of our police would be immensely increased.

The Japanese police, like the rest of the race, are comparatively of diminutive stature. The burly Russian mujiks derided their opponents at the beginning of the war by comparing them to monkeys, but they have discovered by contact that stature does not make a soldier, and those who have had experience with the police here have the highest appreciation of their proficiency.

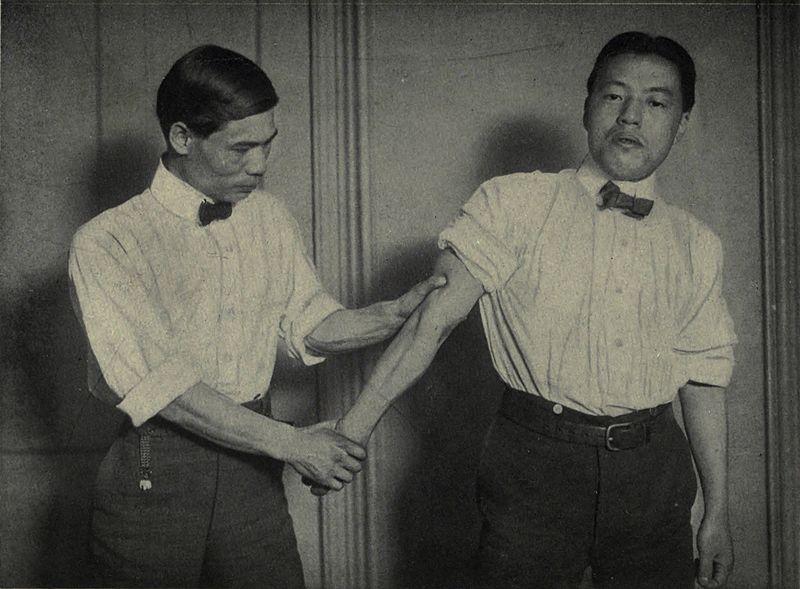

The other evening a drunken English sailor came around in front of the Grand Hotel at Yokohama and made a disagreeable disturbance with foul and profane language and his desire to fight somebody. He was a monstrous, burly fellow, with a knife in his belt, and drunk enough to be reckless and desperate. His demonstrations soon attracted a natty little policeman in a suit of spotless linen duck, who was just about half the size of the sailor. The latter called him a "kid" and other contemptuous names, and promised to eat him if he did not clear out, but the officer did not pay the slightest attention to the jeers, and, to the astonishment of every foreign spectator, took him boldly by the arm and tried to lead him away from the terrace of the hotel, which was filled with guests sipping their after-dinner coffee.

The sailor jerked away, and, shaking a fist as big as a ham at the pigmy policeman, warned him not to lay hands upon a free Briton or he would regret it. Then he made a vicious assault.

In less time than I can tell it the sailor was flat upon his back in the road, only half conscious, and the little officer was tying his shaggy wrists with a cord he had coolly taken from his pocket. Then, blowing a whistle, he calmly awaited the arrival of assistance to take the sailor to the station-house. Before help came the giant seemed to recover his senses, and attempted to struggle. What happened to him I could not see, and do not know, but the officer was equal to the occasion, and ultimately led his prisoner away without the slightest show of concern or excitement.

When we went back to our seats an old resident remarked:

"That was a very pretty exhibition of Jiu-jitsu."

"Jiu-jitsu?" half a dozen people exclaimed.

"Yes, Jiu-jitsu, by which a small man can do a large man in an instant without losing his breath or quickening his pulse beats. It is a science which teaches a man to turn his antagonist's strength and fury against himself; it's brains against muscle. You saw it done, as I have seen it forty times. The native police are trained for it. In the old days it was a secret of the samurai, or knighthood, but to-day it is taught in every public school in Japan, to girls as well as boys. There are hundreds of special schools at which it is taught, and I see that President Roosevelt has been taking lessons in the art.

I have heard that Colonel Wood, the United States military attache, is ordered to make a report on the subject for the benefit of the West Point Military Academy. It is said that instruction is already being given to the midshipmen of Annapolis. The police force of every city in the country would increase their efficiency by Including Jiu-jitsu among their drills. It should be introduced into our schools, and certainly into every gymnasium in the country.

Jiu-jitsu is not a new thing, however. In Japan it is as common as eating or walking, and has been taught in the schools for generations. According to the traditions the science was evolved by a thoughtful samurai (knight), having been suggested to him by seeing two kittens at play. He was the first teacher, and up to the Restoration every soldier was compelled to practise it. After the Restoration, with the craze for foreign ideas and methods, it fell into innocuous desuetude, and was practically obsolete outside of the army and the police, but about 1895, when the triumphs of the Japanese army in China revived the national spirit and pride, a national athletic association was organized under the patronage of the emperor for the purpose of cultivating Jiu-jitsu. Prince Kan-in, a cousin of the Mikado, is the active president, all the young men of the imperial family take a prominent part, and altogether there are now 884,645 active members throughout Japan.

The headquarters of the association are in Kyoto, where, every spring and fall, tournaments are held, and local champions in all the different sports come in from the country to compete with each other for the championship of the empire. Every country village and city ward has its little temple, club house, and instructors, and each its ambitious candidates for distinction, who go up to Kyoto to the imperial meets twice a year. There are minor tournaments at stated dates in all the provinces and counties. Representatives of the emperor are always present to make the announcements and present the prizes. Each prize bears the emperor's bust and autograph, and a legend signifying that it comes from him.

People who know the devotion of the Japanese to their sovereign—they worship him as divine—can appreciate the value that is placed upon the medals awarded, and the enthusiasm which the organization has evoked. It has caused a revival of interest in all forms of sports, especially in Jiu-jitsu. For the last seven or eight years that science has been taught in every school in the empire, and is considered as important as reading or writing. The interest seems to have spread across the Pacific. I read in the home papers that experts have been giving exhibitions in the United States, and, as I have already stated, we are told here that our President has taken it up. If he will make it fashionable, if he will encourage its introduction into our public schools, and he can do it if he will, he will confer an inestimable blessing upon not only this generation, but upon generations to come.

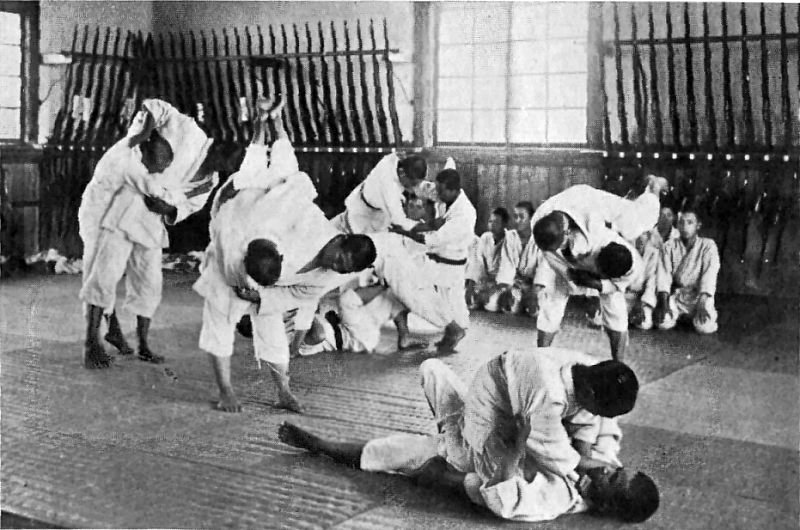

We attended the annual tournament at Kyoto and saw the finest exhibition of Jiu-jitsu you can imagine by amateurs from every corner of the empire. Each afternoon, after the amateurs had finished, we had high-class exhibitions by experts. To our unsophisticated eyes it looked as if the men on the platform were not in earnest; but they were. One of the professors of Jiu-jitsu would stand in the center—some of them are men of slight stature and delicate appearance—and would play with the most robust and cheery young giants just as a cat will play with kittens. It was not ordinary wrestling.

The contestants did not clinch with each other, and struggle and grunt, like the professional wrestlers, but the professor seemed to be able to throw his assailant to the floor almost as soon as the latter touched him, and seldom changed his position. His hands would go out, and he would often do something with his legs, but the young men who attacked him were seldom or never able to get beyond his guard. We couldn't understand why those impetuous athletes, who came toward the professor so boldly and vigorously, should find themselves the next instant on their backs about three yards away. Sometimes he would toss them over his head or shoulders, without an effort. Then, after he had flung a dozen or more all around the platform, he would bow to the presiding officer, bow to the distinguished guests, kowtow to the emperor's portrait and retire.

"Why didn't those young fellows grapple him?" I asked the Japanese gentleman who had been detailed to look after me.

"Impossible," my chaperon would reply, "No one could grapple him any more than an amateur could pink an accomplished fencer."

“Why not? They seemed to be stronger and more active than he."

"Certainly, they have greater strength, but he has superior skill, and uses that skill to turn their strength and impetuosity against themselves. You may have noticed, perhaps, that the fiercer an assailant went at him, the harder was his fall,"

"Yes, that seemed to be so, but I couldn't understand it."

"That's the science of Jiu-jitsu. It is the most perfect of all methods of self-defense."

Curtis, William E. “Jiu-Jitsu, As Seen by William E. Curtis” in A Complete Course of Jiu-Jitsu and Physical Culture. Edited by John J. O'Brien, Physician's Publishing Company, 1905.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.