Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Memoirs of an Arabian Princess: An Autobiography by Emily Ruete, 1888.

In Arabia matches are generally arranged by the father, or by the head of the family. There is nothing peculiar in this, as the same is done even in Europe, where man and woman are allowed to meet freely. Does it not often happen here that a reckless father who has run deeply into debt sees no way out of his difficulties but by the sacrifice of his pretty daughter to some creditor; or that a fashionable, pleasure-loving mother hurries her child into marriage for the sole purpose of obtaining an undisputed sway?

Amongst the Arabs there are just as many despotic parents, who care as little for the happiness of their children, or listen to the voice of conscience. But it is not abuse of power alone which makes parents in those parts choose for their children; they are compelled to do so by the retired life of the women; though even by this seclusion a meeting with men cannot always be prevented. But it is a general rule that a girl must not see (except perhaps from the window) nor talk to her future husband before the evening of her wedding. Yet he has not been quite a stranger to her—his mother, his sisters and aunts have had frequent opportunities of describing him, and telling her everything about him that may be of interest.

Sometimes the young couple have been acquainted in early youth, as girls are permitted, up to their ninth year, to associate freely with boys of the same age. In such a case the young man goes to the father of his old playmate to ask for her hand, after having secured her own consent through the mediation of his mother or sister.

In all such cases the cautious father asks: "But where have you been able to see my daughter?" To which the reply is made: "As yet I have never had the good fortune to see your honoured (makschume) daughter—but I have heard a great deal about her charms and virtues from my own people."

If the candidate does not suit, he is straightway refused by the father, though, as a rule, the latter asks for some little time to take the matter into consideration. He does not mention a word at home about what has occurred—but secretly and rigorously he watches the conversation between his wife and daughter. Occasionally, and in quite an indifferent manner, he will speak of his intention to give a small gentlemen's party in a few days, mentioning the names of his friends with as little concern as possible if the women require to be told them. If they appear to be pleased at hearing the suitor's name mentioned, he knows that some understanding exists already between the two families. Then only he informs his daughter that N. N. has asked for her hand, and asks her opinion. Her yes or no are almost always decisive—only a despotic father takes the decision upon himself without waiting for his daughter's acceptance or refusal.

Our father, too, showed in such questions his sense of justice, and left his children to decide their own lot. A distant cousin of ours, Sund, proposed for my elder sister Zuene when she was barely twelve years old. My father disapproved of his proposal on account of her youth, but did not like to decline it altogether without having first consulted his daughter. Zuene had lost her mother, and having no one to advise her, she was so pleased with the idea of being a married woman soon, that she insisted upon accepting him, and my father gave his consent.

There are cases, it is true, in which children are affianced and married in very early youth. Two brothers had agreed upon the intermarriage of their children, and, as it happened, they had only one child each, the one a son, the other a daughter. The marriage was already talked of when the boy was seventeen, and the girl seven. The boy's mother, who lived on an estate not far from my own, a very prudent and sensible woman, often complained to me of her husband and her brother-in-law, who insisted upon her accepting a little child as daughter-in-law, whom she would have to nurse and educate first, while on the other hand the girl's mother was inconsolable at having so soon to part with her daughter. But they both only so far succeeded as to have the wedding postponed for two years. I do not know how the matter was finally settled, as I left Zanzibar soon after.

All friends and acquaintances are formally informed of the engagement by handsomely-dressed female slaves, who, sometimes to the number of twenty, go from house to house with the announcement and the invitation to the wedding, for which message they are richly rewarded at each house.

The paternal home of the bride is now the scene of much life and bustle, for the wedding generally takes place within four weeks. Under any circumstances the betrothal never lasts long, as but few arrangements are necessary in our blessed South. There we know nothing of the hundred and one things considered indispensable to Northern people on such occasions, and an Eastern bride would become speechless with surprise at the sight of a European trousseau. Why are people in these parts so very fond of loading their new bark with such a quantity of unnecessary ballast?

The dowry of an Arab bride is comparatively a small one; according to her rank and wealth it consists of rich dresses, jewellery, male and female slaves, of houses, plantations, and ready money. She gets presents from her parents, from those of her affianced husband, and from the latter himself. All this remains her personal and private property, and the cost of her dowry is never deducted from her share of the patrimony.

The making of the bride's dresses takes some time, for a lady of rank has to change her toilet twice or thrice a day during the first week after her marriage. A bridal dress, like the white robe and veil here, is not worn in the Eant, but the bride must put on perfectly new garments from head to foot—the colour of the dress is left to her taste. Some appear in all the colours of the rainbow, yet their costume is neither ugly nor without taste.

Special perfumes are prepared, which play an important part at the wedding feast—the Ehia, a costly mixture of powdered sandal-wood, musk, saffron, and plenty of ottar of roses, is used as an ointment for the hair, and a pleasant incense, made of the wood of the "ud" (a species of the aloe), of the finest amber, and of a great deal of musk. An Eastern lady never can get too many perfumes.

Then comes the baking, the preparing of sweet-meats, and the slaughtering of cattle, which occupies all hands fully.

The bride herself has yet to go through several unpleasant and tiresome ceremonies. During the last eight days she has to stay in a dark room, nor must she put on any of her finery, so that she may appear all the more resplendent on her wedding-day. All this time she is a much-to-be-pitied creature—visit follows upon visit, all the old women whom she knows, and her nurses foremost of all, whom perhaps she has not seen for years, come to her with hands open ready to receive. The chief of the eunuchs, who has shaved off her first hair, who is very proud of this service of honour rendered to her once, begs to offer his congratulations, and returns his way with a souvenir—either a costly shawl, a ring for the little finger of the left hand, a watch, or some guineas.

The bridegroom is spared this imprisonment in a dark room, but otherwise he has to undergo quite as many trials. All those who have ever been in his service or in that of his bride come to him before calling upon her, and in this way they obtain double presents.

The bridegroom stays at home during the last three days, and only his most intimate friends visit him. But there is a lively intercourse between the two families—for there is no end to the interchange of compliments and of presents between bridegroom and bride.

The great day appears at last. Generally the nuptial ceremony is performed in the evening at the bride's house, and not in the mosque. The act is performed by a Kadi, or, if no such is to be had, by a reputedly devout man. It may appear strange to a European, that the principal person, the bride, is not present herself during the solemn act; she is represented by her father, her brother, or some other near male relation.

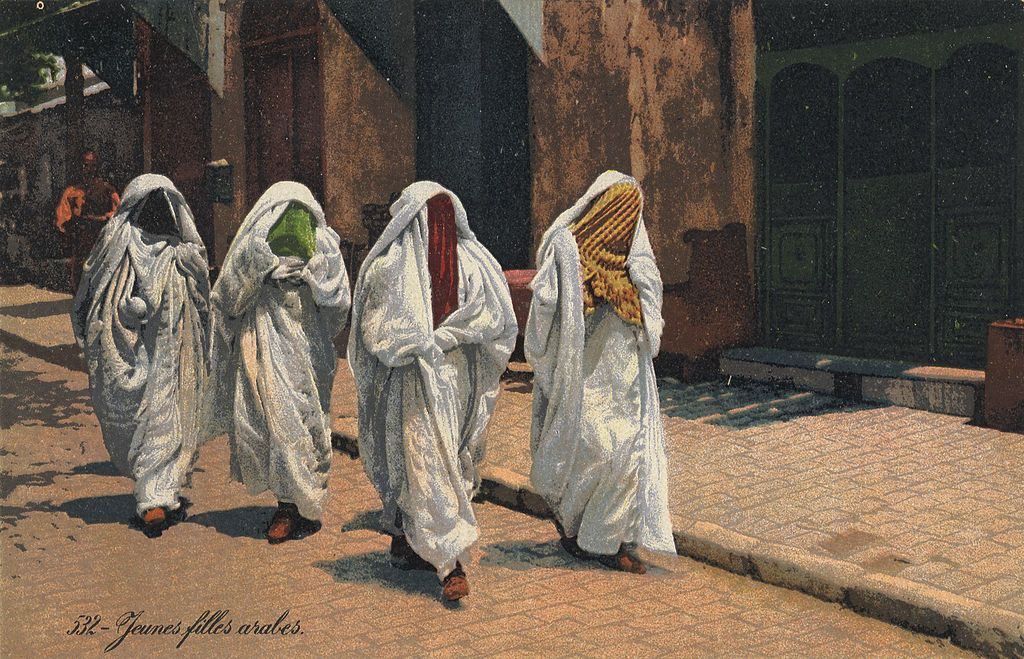

She only appears before the Kadi in person if she has no male relations at all, to be united to her bridegroom with the customary ceremonies. In this case, she enters the empty room first, completely muffled, after which the Kadi, the bridegroom, and the witnesses are admitted. After the conclusion of the ceremony, in which the voice of the bride is barely audible, the gentlemen leave first to let the newly-married wife retire to her apartments.

All the gentlemen, the bridegroom included, partake of a sumptuous feast. Whilst this lasts, the room in which it takes place is richly perfumed with incense of ud and of ottar of roses.

The surrender of the bride to the bridegroom does not always follow upon the ceremony, but in most cases three days later. Numerous persons are now engaged in dressing her in her finest garments, and at about nine or ten in the evening of the third day she is conducted by her female relations to her new abode, where the bridegroom receives her in company with his male relations. Before the entrance to the private rooms, leave is taken with many congratulations and blessings, and the company then retire to the reception-rooms on the ground floor, to celebrate the marriage by merrily feasting for several days.

Some rules of etiquette are always to be observed when the bridegroom has entered the bride's apartment. If her rank is higher than his, she remains quietly seated, nor deigns to speak to him until he has first addressed her, and meanwhile still retains her costly mask, which covers her features. Then, to prove his affection, and as a bribe for the removal of the mask, the young husband places at her feet such presents as his means can afford. A few pence will suffice with poor people—but by rich ones large sums are spent on these offerings.

On the same evening, a general entertainment commences in the house of the young husband, which lasts three, seven, and even fourteen days. Friends, acquaintances, strangers—all are welcome, and may eat and drink as long as they will. There is, of course, neither wine nor beer, and even smoking is not allowed with the sect of the “Abadites," to which we belong—but that does not prevent people from being very merry and jolly. There are plenty of good things to eat, and almond milk, lemonade, &c.; songs are sung, warlike dances are performed, and stories are listened to. Eunuchs perfume the rooms with ud and sprinkle rose-water over the guests, out of silver dishes.

The ladies always remain together till midnight, but the gentlemen stop all night till they are called away to prayers in the morning.

Wedding tours are not known in the East. The young couple spend their honeymoon quietly at home the first week or fortnight, invisible to the outer world. After this time, the young wife receives visitors, and in the evenings her apartments are filled with her female friends, who have come to offer their congratulations.

Ruete, Emily. Memoirs of an Arabian Princess: An Autobiography. D. Appleton & Company, 1888.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.