Note: This article has been excerpted from a larger work in the public domain and shared here due to its historical value. It may contain outdated ideas and language that do not reflect TOTA’s opinions and beliefs.

From Early Greek Philosophy by Alfred Benn, 1908.

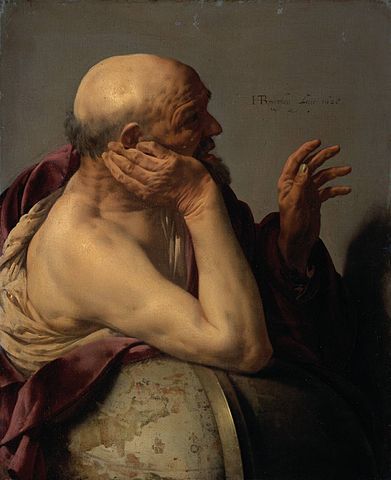

Heracleitus

So far the philosophers with whom we have had to deal have been little more than names, distinguished from one another by purely intellectual attributes, not recognisable as living personalities. But Greece was the very land of strongly-marked, vivid, individual characteristics, as the Homeric poems already show, and the personal note, so conspicuous for two centuries in her lyric poets, could not fail ultimately to make itself felt in the creations of abstract thought. It meets us for the first time in Heracleitus of Ephesus, universally acknowledged as the greatest of the pre-Socratic philosophers, and probably destined to rank for original genius among the greatest that the world has ever seen.

We may add that with him the separation of philosophy from science in the strict sense begins. His interest lies solely with the one universal law of nature, possibly generalised from particulars, but not dependent on them, rather dictating to them what they shall be.

Science and common sense have always protested against such an assumption: our own Francis Bacon has given the weightiest and most splendid expression to their protest; but others were found to utter it long before him. We have to ask, however, whether science itself could have dispensed with those paradoxes of pure thought, whether Bacon himself did not miss more truth by a servile adhesion to supposed facts than the Greeks missed by a sovereign disregard for them.

Our personal knowledge of Heracleitus comes almost entirely from what fragments of his composition survive; for no reliance can be placed on the stories current about his life, beyond the bare statement, confirmed by some references of his own, that he flourished at the end of the sixth century B.C. Thus, in the order of succession he comes immediately after Anaximenes, the last representative of the Milesian School; and in fact he seems to have followed the Milesian method of seeking for a universal principle, a substance of which all things are made. Two elements had already figured in that capacity. Water and Air. Heracleitus supersedes them by a third, which is Fire.

He appeals to its function as a universal medium of exchange. 'As goods are given for gold and gold for goods, so everything is given for fire and fire for everything.' Our philosopher would have entered heartily into the modern speculation that every form of energy is electric and the whole material world merely so much congealed electricity.

For Heracleitus fire is what we now call the Absolute, the eternally self-existent reality underlying all appearance. 'This order of things (κόσμος), the same for all, was not made by any god or any man, but was and is and will be for ever, a living fire, kindled by measure and quenched by measure.'

If any one likes to call the eternal One by the consecrated name of Zeus he may, only on the understanding, as seems to be hinted, that it is not to be the Zeus of the poets, 'a magnified non-natural man,' but an impersonal power, and a relation rather than a substance.

There is an obvious contradiction in describing fire as both ever-living and as alternately kindled and quenched. And the Ephesian sage would not have hesitated for a moment to acknowledge that there was a contradiction.

For, according to him, contradiction is the central fact of existence, the spring, as we should say now, that makes the wheels of the universe go round. In human affairs this is clear enough. 'War is the father and king of all things': it originates our social distinctions, 'making some gods and others men, some slaves and others free.’ ‘Homer was wrong in wishing strife to perish; and he ought to be flogged out of the competitive games.’

It seems likely that the contempt of Heracleitus for Pythagoras may be explained by the same cause that accounts for his depreciatory estimate of Homer. When the Samian philosopher divided the great principles of nature into a series of antithetical couples he was right; but his whole system was vitiated by the failure to perceive that these opposites are necessary to each other's existence, that the whole frame of things is determined by their conflict and interplay. And that is just what makes fire so representative an element, so fit a type of the world-pervading law.

Fire lives by struggling with and assimilating its own opposites, perishing at the moment of its complete triumph. Speaking more accurately, it only seems to perish, living again as air, whose birth is the death of fire, as similarly water lives by the death of air, earth by the death of water, and fire once more by the death of earth.

The Flux

This endless process of transformation was summed up by the Greeks in two words, not known to have been used by Heracleitus himself, but admirably expressing his philosophy: πἁντα ῤεῖ— all things flow. In some instances the universal flux is attested by the evidence of our senses: no man bathes twice in the same river; in others we know it by reason: ‘a new sun rises every day'—a conclusion deduced, we must suppose, from the fact that our own fires need perpetual supplies of fresh fuel to keep them burning.

Solid earth must have proved, in more senses than one, a hard nut for the theory to crack ; for thousands of years had still to pass before science could show that the most quiescent bodies are composed of molecules in a state of perpetual rotation and revolution. Probably Heracleitus argued that as earth is potentially fire, water, and air, it must partake in some way not evident to our imperfect senses of their mobility and evasiveness.

That which in material bodies presents the appearance of a perpetual flowing from one form to another, assumes in our sensations, appetites, and ideas the still higher aspect of a universal relativity. 'If all things were turned to smoke the nostrils would distinguish them'; and in fact 'souls do smell in the underworld';—where, as seems to be implied, everything is smoke. Fishes find salt water life-sustaining which to men is poisonous.

'Asses prefer chopped straw to gold.'

'Swine bathe in mud, fowls in dust or ashes.'

‘The most beautiful ape is ugly when compared with a man; the wisest or most beautiful man would be an ape compared with the gods.’

'Good and evil are one. Physicians expect to be paid for inflicting all sorts of torments on their patients.’

‘We should not know there was such a thing as justice did injustice not exist.’

'To God'—or, as we should say, from the absolute point of view—'all things are fair and good and just. The distinction between just and unjust is human.'

'God is day and night, winter and summer, war and peace, plenty and famine.' Yet for us also the union of opposites holds good. 'Health, goodness, satiety, and rest are made pleasant by sickness, evil, hunger, and fatigue.’

The Logos

Heracleitus might have pushed his negation of all the usual distinctions embalmed in common sense to a system of dissolving scepticism, in which every fixed principle, whether of knowledge or of action, would have disappeared. But he did not go to that extreme. After the doctrine of fire as the world element, after the dogma of an all-pervading relativity, comes the third and greatest idea of his philosophy, the idea of universal law and order.

We have already come across it in that great sentence describing the Cosmos as an everliving fire kindled and quenched 'according to measure.’

The meaning is that fire transforms itself into water, water into earth, and so on on a basis of strict quantitative equivalence, so much of the one being paid in and so much of the other paid out. To the same effect we are told elsewhere that 'the sun will not transgress his measures, or the Erinyes who guard Justice will find him out.'

In Greek mythology the Erinyes had for their original function to avenge the violated sanctities of blood-relationship, and more particularly to punish the crime of matricide, a function subsequently extended to the punishment of all crime. By a crowning generalisation they are here thought of as the guardians of natural law in the widest sense.

Our philosopher calls this world-wide law by a name which had a great future before it. It is no other than the Logos, so familiar to us as the Word, proclaimed in the proem to St. John's Gospel, which became incarnate in Jesus Christ. St. John had derived it perhaps from Philo of Alexandria, Philo from the Stoics, and the Stoics from Heracleitus.

To the Ephesian sage also, as to the fourth Evangelist, the Logos is the light that lighteth every man that cometh into the world—the reason within him by which the cosmic Reason is revealed, his individual portion of the universal fire. For just as Anaximenes had assimilated the breath of life, the animating and sustaining spirit of man, with the all-constituting Air, Heracleitus assigns the same twofold activity to his elemental Fire. It was a common principle in Greek philosophy that like knows like: and so the burning stream of consciousness within us recognises the eternal flux without—recognises it also as reasonable, or rather as more reasonable in proportion to its vastly greater dominion and duration.

Agreement, community, identity are the essential notes of reality and reason. It will be remembered that the eternal order was, in modern phraseology, established as objectively true by being the same for all men. 'All human laws draw their sustenance from the one divine law'; and to judge things truly we should hold fast to the common reason, even more forcibly than good citizens cling to the law of the State, which they defend like the city-wall, putting down the insolent self-assertion and arrogance of individuals. Individual sovereignty and the right of private judgment divorced from reason are fantastic illusions. Such individuality is at its height when we are asleep and dreaming, each of us in a world of his own. When we are awake it is the same world for all.

Not that Heracleitus believes in the wisdom of the majority as an infallible guide. 'Most people are foolish and bad; the good are few, and one man is worth ten thousand if he be the best.' Nevertheless personal authority should go for nothing; arguments not words are the thing. Unfortunately argument is thrown away on the generality; as we saw, asses prefer chopped straw to gold. And the law of relativity itself explains why the law is not understood. Fire is only intelligible to the soul of fire, to the dry soul. Degenerating minds in which the vital spark turns to water are thrown out of touch with the essence of things: theirs is a savour of death unto death. More particularly our prophet's own countrymen, the Ephesians, are a hopelessly irreformable set with a vicious hatred for superior persons as such. Better if the adult population were all to hang themselves and leave the city to their children.

Such utterances are marked with the essentially aristocratic stamp of early Greek thought. It is probable that in the case of Heracleitus this contemptuous estimate of the vulgar was accentuated by a rationalistic disdain for the new popular religion. When he observes that the ritual of Dionysus would be shameless indecency were it not an act of divine worship, his reference, standing alone, might be meant for no more than an illustration of the universal relativity. But when taken in company with his attack on the Bacchic mysteries and the prevalent rage for secret ceremonies of all kinds, the words can only be interpreted as an unequivocal condemnation of the Orphic revival. Plato spoke no otherwise of the same manifestations a hundred and twenty years later, and Huxley's comments on Salvationism are less severe.

Benn, Alfred William. Early Greek Philosophy. Archibald Constable & Co, 1908.

About TOTA

TOTA.world provides cultural information and sharing across the world to help you explore your Family’s Cultural History and create deep connections with the lives and cultures of your ancestors.